Thematic similarities among three novels written by three different South Asian- American women writers

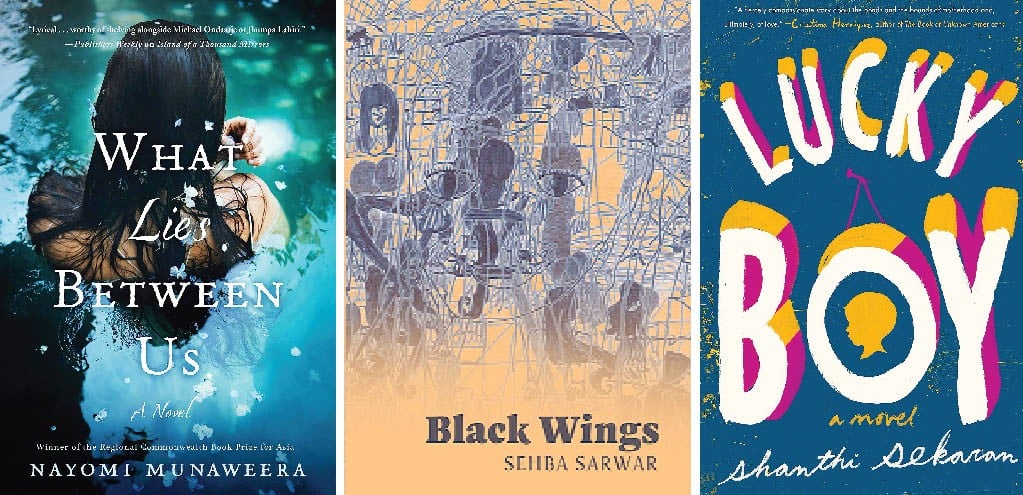

Last month I ended up reading three English language novels written by South Asian-American women authors from three different ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds.

The first one of these remarkable women writers, Shanthi Sekaran was born and raised in the US and is fluent in Tamil. Sekaran’s parents are from South India. Her novel Lucky Boy was selected by the San Francisco Public Library last year as its, ‘On the Same Page’ book to be read throughout the city. The novel deals with the issue of an undocumented Mexican woman ending up in jail, getting separated from her toddler son, an issue that has made many Americans reassess their conscience.

Nayomi Munaweera, born in Sri Lanka to Sinhala parents, grew up in Africa, Europe, and the US. Her second novel What Lies Between US is somewhat reminiscent of her debut novel which I reviewed a while ago for these pages. The story is told from the point of view of a narrator, who, after her father’s death, emigrates from Sri Lanka along with her mother to the US. In her new home, she marries a white American man who is an artist and gives birth to a daughter.

The third novelist is Sehba Sarwar, whose Black Wings was republished in the US in 2019 in a much smaller size. Black Wings has two narrators, daughter and mother, Yasmeen and Laila. The novel begins when the mother visits her daughter in the US. There are issues the two have to sort out, primarily revolving around Yasmeen’s twin brother’s death.

As I finished reading Black Wings, I couldn’t help but marvel at the thematic similarities among these three novels, while being so very different outwardly. To begin with, all three novels put motherhood at the centre of the text. All three point towards a relationship between trauma and immigration. Finally, all three deal with the death of a father figure - signifying a collective desire for the demise of patriarchy.

All of these novels also play with name politics. Sekaran’s Lucky Boy is divided into two sections named after the two mothers, Solimar the Mexican mother, and Kavya the Indian American mother. Solimar is a composite of sol (sun) and mar (sea). The novel indicates that the Mexican mother, who throughout is referred to simply as Soli, would end up getting her son (sun) back. It seems like Sekaran had unconsciously decided that a tragic poetic justice would have to be meted out to Solimar in the end. Munaweera’s protagonist remains unnamed and thus becomes an allegory for Sri Lanka’s tortured history. Laila, meaning night/dark, of Black Wings, is apt because of the secrets she shares and withholds.

All three novels push the literary envelope.

Lucky Boy does away with the need to negotiate white power structure. Although the two mothers never actually meet even as the child changes hands, white characters provide a landscape for non-white female characters to test the limits of their agency and desire. Munaweera employs the metaphor of child molestation as a vehicle to contest the national memory of trauma. Unlike her first novel, Island of a Thousand Mirrors, she does not bring in the Sinhala vs Tamil civil war to the foreground, though one can sense it simmering distantly. Instead, it is the unnamed child protagonist who emotionally shuts off due to the molestation she suffered by a trusted servant. When the mother and daughter confront the issue, the mother points out that it was actually the father, not the servant, who in fact tried to protect her. But it is also possible that the mother knows only her side of the truth. Therein lies the power of the novel.

Sehba Sarwar sets up a confrontation between a daughter and mother. It begins when Yasmeen asks her mother to explain her absence during a stormy night, which caused her twin brother to go out looking for her, eventually leading to his death. The mother admits that she went to see her lover, someone she had loved even before she married Yasmeen’s father. Yasmeen then asks her mother if her lover was the father of Yasmeen and her twin brother. Despite the mother’s chiding or clarification, Sarwar cleverly allows the doubt to linger in the reader’s mind. By doing so, Sarwar evokes the Islamic reference to people being called upon by Almighty by their mother’s name on the Judgment Day, in order to save her honour. Yasmeen’s father’s death is a result of guilt and grief, again, highlighting the approaching end of patriarchy.

In all three novels, the mother returns to the native land to find inner peace or resolve simmering issues. Soli of Lucky Boy succeeds in kidnapping/rescuing her child from Kavya’s house and eventually crosses over to Mexico. The mother of the unnamed protagonist of What Lies Between Us returns to Sri Lanka to live there while her daughter goes to Cal and starts living independently. In Black Wings, Yasmeen and her two children return to Pakistan for a vacation and visit the spot in Murree hills where her brother had met his death. All novels reference significant political events such as civil wars and 9/11. What Lies Between Us and Lucky Boy signal that the US is not a safe place to raise a child, a stance Black Wings does not fully share, though Yasmeen and her children are victims of the fractured family life that the US is notorious for.

Of the three, Black Wings is the most tautly written and the shortest in length. Lucky Boy takes a risk with its length but somehow manages to keep the reader’s interest. What Lies Between Us balances lush and psychologically intense prose. And since it is also about a mother who kills her own child, it ends on a note of homage to Toni Morrison and her novel Beloved. Munaweera does so after starting on a Rushdian chord and then gradually shifting to an American scale. This seems like a conscious choice.

There’s one thing that separates Black Wings from the other two, that is, it does not explicitly explores class politics, both in Pakistan and the US. The prose of all the three texts remains rooted in a middle-class register, though there’s inventiveness here and there.

Being a writer of colour, it is important to acknowledge the themes we take on. It is equally important to create a text of colour. South Asian-American writers are not there yet, but I believe we’ll get there. Soon.

The writer is a librarian and lecturer in San Francisco. His most recent work is Cafe Le Whore and Other Stories