The rare bird reminds us of the majesty of quiet wisdom in a noisy world

On one cool night in Lahore, we were returning home after attending the 80th birthday of a friend - perhaps most special to us in this city of Lahore. He is a treasured person of spiritual and aesthetic qualities, and it has been an intimate celebration of subtlety, spontaneity and refined cuisine. Rare qualities in this flamboyant city of colour, noise and over-eating.

His son, who was present at the little gathering, just published a hand-bound book of reprinted essays written by one Professor Timothy Winter of Cambridge University.

Dr Winter’s Zen koan-like aphorisms or short statements of deep insight, delight us as we flip through the book in admiration of its elegant, Lahori binding and recycled paper.

"Use words in your preaching only if absolutely necessary", a phrase from this book was to come back to me later the same evening. I mused about the auditory nature of preaching. Without words, there is no preaching, so what might preaching be without words or sound? It would become transmuted into an enactment in silence and meaning-making. To me, the special person whose birthday we were celebrating is just the man of enactment, silence and meaning.

As we drove home later that night, I was shown by the enactment that nature has its silent sages.

Just near the lane of our friend Khalid’s house, my husband slowed down the car, and whispered softly: "A large, silent bird has just flitted by…" We drew upon the main road next to a verge of tall, old Arjun trees.

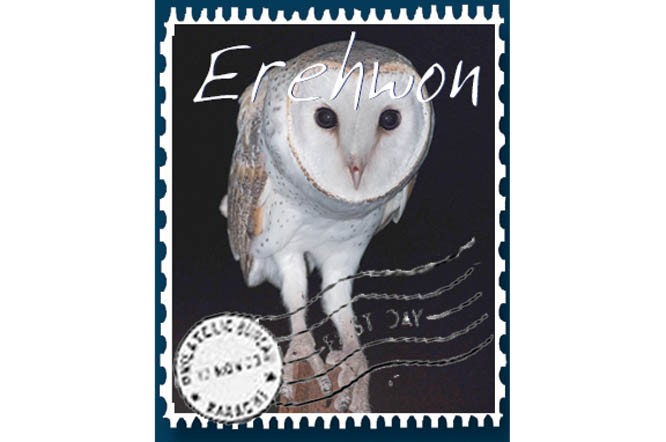

Perched on low-hanging telephone wires, a sizeable bird sat upright on its claws, some 10 feet above our car. In a 100 degree turn of its neck, two large eyes, set in a heart-shaped, white face swivelled around to focus on us. All of these were signs that we were perhaps looking at an owl.

We had spotted a barn owl, a rare thing indeed in Lahore. Only a second sighting in the two decades we have lived in this neighbourhood. The previous sighting - as noted in our bird book - was on January 6, 2017, on a street close-by.

Near his house, our friend Khalid knows this bird and has seen it for sometime. Called a Tyto owl, after the Greek word that means owl, the barn owl is a separate branch to the common owl family. Khalid is right, for the barn owl is non-migratory and tends to settle in one place over its lifetime. Chances are that the bird I saw two years ago, the bird Khalid had seen over some time, and the bird we spotted the night I am talking about in this column, are all the same individual.

Ever observant, my husband saw a hole in the trunk of the Arjun tree where we had halted to spot the owl. As it turned its focus on us with its binocular eyes, the bird flitted away in the direction opposite to the hole.

We suspected therefore that it had a growing family in the hole. Normally laid in autumn and devoid of a dedicated nest, owl eggs are either perched on a ledge or at the bottom of a hole in a tree-trunk. This Tyto owl seemed to be luring us away from locating and hence endangering the site of its future chicks that might lie at the bottom of the hole in evidence.

Subtle and silent, the barn owl is only seen rarely. It is considered a scarce resident of the old settlements in Lahore. Its presence has also been documented in Bahawalpur and Karachi’s Landhi and Malir areas.

Our bird’s hallmark is its white, heart-shaped face set with dark eyes. This facial disc is like a funnel, or satellite dish for catching the sound, the sense that is central to the life of this being. They can rotate their heads three-quarters of a whole circle as if pivoting from 12 to 9 o’clock while keeping the rest of the body still.

What’s more, Tyto owls have their ears placed on their heads in such a manner that sound reaches them at slightly different times. Using this 30 millionth of a second difference in hearing, the owl turns its head until sound reaches both ears at the same time, at which point, it is directly facing the source of the sound.

Having precisely located something using its ultra-sensitive ears and eyes, its absolutely silent feathers allow the owl to hunt without noise to distract either itself or its prey. Favourite meals are garden shrews and mice that scurry at night around verges and rubbish heaps. Unaware of anything overhead, these creatures become active at night, just when the owl is alert. Even its downward-facing beak, like an aquiline nose, helps a clear field of vision and the passage of sound without deflection.

In so many diverse cultures, the owl signifies great wisdom, and in the Aboriginal Canadian tribes, denotes the high status of spiritual leaders.

As we made our way home, I reflected on a night of rarity and symbolism about insight. It had been a time of remembering the majesty of quiet wisdom in a noisy world.

Image courtesy: Chris Steeles, Flicker