Painter and conservationist Dr Ajaz Anwar talks about the many water tanks in Lahore that he saw in his childhood, such as Rattan Chand Saray Talaab, next to the office of The Pakistan Times, which were built for public consumption or as part of historical monuments, but were mostly replaced

Riding my bicycle rented for two annas an hour, passing through Queen’s Road, I had always marvelled at a strange square edifice with steps descending into it from all four sides. Later, I learnt that it was popularly known as Sukka Talaab because it was a tank with no water in it.

Water tanks have their origins in the great stepped bath of Mohenjodaro and even earlier. There had always been a water pond outside villages since antiquity, for animals and homo-sapiens alike. A small water tank with a fountain was incorporated in the design of the mosque. However, independent water tanks were built for public consumption or as part of historical monuments. Hauz e Khas was built by Firoz Shah Tughlak in Delhi, around 1375, to facilitate the purchase of wheat by the labour during the famine.

Another water tank at Sahsaram, Bihar, accommodates the tomb of Farid Khan/Shershah Suri, builder of Asia’s largest fort -- Rohtas -- at Dina, near Jhelum. The same monarch ordered Lahore to be razed to the ground for being so rich a city, on the very route of an invader. Before his orders could be carried out, he himself died in a gun-powder blast. To presume it to be a curse from the many holy personalities lying buried in Lahore would be farfetched. The real revenge, though unintended, could be Hiran Minar at Sheikhupura, built in the memory of Mansraj, a pet deer of Sheikhu Baba, as Mughal Emperor Jahangir was reverently addressed. The large tank in the centre of which an octagonal Pavilion is situated was so designed perhaps as a satire to the tomb of Shershah Suri who had sent Jahangir’s grandfather Humayun into a 15-year banvaas.

The only notable event of this period was the birth of his son Akbar, in Umarkot, which was celebrated with the distribution of musk. This writer had the honour of having helped design/rebuild the monument marking the birthplace of the prince, under the supervision of Col Qazi, then posted there.

In Lahore, Nadira Begum’s tomb, next to Mian Mir, was similarly built inside a water tank (to be discussed in later dispatches).

There were other water tanks in Lahore that I saw during my childhood, mostly usurped, namely Rattan Chand Saray Talaab, next to the office of The Pakistan Times, Melaram, near Railway Station where tall hotel buildings have now come up. These were supposed to be under the protection of the Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB), but were all sold away through shady deals.

Bansi Sagar Water Tank, a fine fishing spot in Cantonment, near Dharampura, however, is still functional because the locals protected and saved it. The water tank on Waris Road/Queen’s Road corner was built by Lala Lajpat Rai, brother of Jaspat Rai and Lakhpat Rai (Kot Lakhpat was named after him or maybe he owned this land, according to an expert on Lahore, Naeem Dar). An old brick kiln mound overlooks the water tank. It was filled with water from a tributary from the Mughal-era canal -- the Lower Bari Doab, restored by the British soon after 1861. Tributaries from this canal irrigated greenbelts as far as University of the Punjab. This source of water was later severed. Old folks of the neighbouring Bhundpura turned the stepped tank, then devoid of water, into an amphitheatre of sorts. Wrestling bouts, cricket and hockey matches were held, and it came to be known as Sukka Talaab.

In later years, the Fisheries Department had the brilliant idea to adopt it. The tank was filled with water from the nearby tube well. The water collected in a small, raised reservoir with a fountain was allowed to fall into the tank via a sloped marble slab having zigzag or herringbone engraved designs like the one at Shalamar Bagh, though much smaller, produced a rippling sound effect.

Fish seedlings were released into it. Anglers who previously had to peddle long distances could now drown their earthworms here. A two-rupee licence fee was willingly paid for which they were allowed to land three fish measuring more than 12 inches (though, rarely a fish caught there measured 12 inches). During the 1960s and ‘70s the tall peepal was a happy rendezvous spot where anglers knew the fish would gather to feed on the fruit dropping from the tree. During one monsoon it rained so much that blue-gold, as the harvested water is now called, overflowed and the imprisoned fish escaped. The drivers of the fire-brigade engines stationed diametrically opposite the tank, watched with popping eyes the children manually catching fish on the Queen’s Road. Incidentally, a double-decker of Omnibus service negotiating a curve on the wet road, skidded trying to save the fisher children. A photograph of the vehicle lying sideways adorned the following day’s The Pakistan Times. It was clicked by FE Chaudhary. The Fisheries Department put a gauze net around the tank to prevent fish from escaping in the event of similar rains.

Mounting water/electricity bills could not have been paid out of the two-rupee licence fee. Only those with no connections lost their connections. The connection was severed. Local or provincial government would not help. For the fertile minds had some other designs to strike gold.

A large part of the hill was severed like the Katti Pahari of Karachi. The tall banyan tree was mysteriously felled, the fire brigade station too was decommissioned. In later years, a girls college was set up over the hill, named after a monarch who had not paid a penny towards it. (It is universal practice not to name any monument or road after a living person; MM Alam Road was a befitting exception.) The Fisheries Department departed. Some old-time anglers still ventured, albeit for free. Rahoos and Kalbonses could not migrate to more watery pastures. Since the Omnibus was killed on purpose, and auto cars multiplied in horrifying numbers, workshops mushroomed everywhere. Waris Road too was not spared. Previously, it was a posh locality where Bapsy Sidhwa lived and based her award-winning novel The Ice-Candy Man. The place where Theodore Phailbus and Hurmusjis lived was turned into a ballistic lab. Motor workshops were built around the water tank. Though there is no tradition of providing a ‘relieving’ facility at workplaces, while usurping the water tank premises, they built toilets directly over its sides.

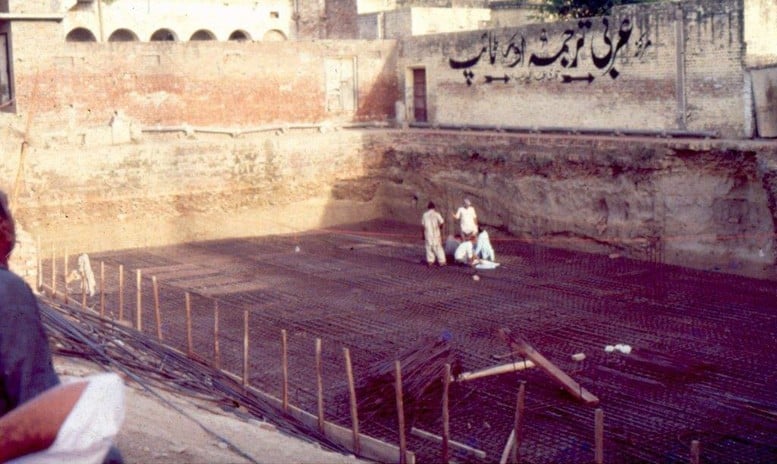

Fish trying to survive, could still be seen somersaulting in the obnoxiously polluted environment. Ultimately, the water tank was drained and filled with debris. A wall was built around it to hide what was going on behind the scene, further straining the financial resources of the ETPB. A huge gate was installed to deny the public access to it, the keys of which are entrusted to a motor car dealer.

A high-rise plaza is the intention of land grabbers. It would certainly violate the privacy of Fatima Jinnah Medical College girls’ hostel. Moreover, it is a trust property gifted to the people of Lahore by Lajpat Rai, and cannot be sold or usurped.

Restoration of the tank in question is easy and most cost-effective. Not all is lost; all lies buried intact. A wake-up call by the Lahore Conservation Society is timely. The monthly meeting attracted some locals who narrated the oral history of the tank, including a snake-charmer, though no buffalo to represent…

(Note: during the early 1980s, Bheroan ka asthan, the oldest Hindu shrine in Lahore, the tank of which was sold away for only nine lac rupees; late Kale Khan told this scribe; now an ugly Shama Plaza stands there.)

To be continued