A look into the tradition of marsia and how it became an integral part of modern Urdu poetry

Poetics of marsia (elegy) has demonstrated a dynamism which has enabled it to survive in the face of time. Though still deeply embedded in the tragedy of Karbala, its poetics not only keep reinventing narrative modes, diction, style and formal elements but also strive to reinterpret the fundamental message of Karbala in the contemporary perspective of power structure.

Under the colonial regime, marsia - like other classical genres - came under fire. For instance, Kalimuddin Ahmad opined that "as a marsia writer cannot stay impartial, he fails to write something of substance". Obviously, Ahmad’s judgement is entrenched in the European canon that would advocate universalism. (Paradoxically, only the European literary canon was regarded universal - purported to be copied at the cost of indigenous canons.) "Characters of marsia are not wholly Arab or Indian and lack individuality," said Ahsan Faruqui and Josh Malihabadi. Again, the stress on individuality was a reflection of how colonial modernity was building up a case against classical poetry and its poetics.

Being a genre of poetry developed in a multicultural Mughal India, marsia was bound to present an amalgamation of cultures. This was not a distortion of history, instead an imaginative way to search human significance in history - a paradox, indeed. It was none other than Josh - a critic of marsia - who played a significant role in laying the basis of modern marsia. The trajectory of 20th century marsia shows that the said criticism, though harsh and a little unjust, forced marsia poets to reevaluate the classical tradition of this genre. They also took it as an opportunity to discover the dynamic elements of the poetics of marsia. What has been termed jadeed (modern) marsia, originates in the writings of those who migrated or had been living in Pakistan pre-partition.

A brief history of Urdu marsia reveals that it is as old as Urdu poetry. Its earliest instances have been traced to the 16th century Deccan, the first centre of Urdu poetry. In the divan of Muhammad Quli Qutub Shah (1580-1611), there are five marsias composed in the form of ghazal. Among other Deccani poets who tried their hand at marsia, Wajhi, Ghavasi, Nusrati, Hashmi and Khushnood deserve to be mentioned. Mirza particularly played a vital role in developing the poetics of this genre.

It was he who divided the story of Karbala into rukhsat (departure), rajaz (pain), jang (battle), shahadat (martyrdom). He apparently did this to create a dramatic effect, and to emphasise the psychological exposition of the heroes of this tragedy. Hence began a long process of the appropriation and indigenisation of the tragedy of Karbala. Delhi emerged as the new, great centre of Urdu poetry in the early years of the 18th century. Though Shah Hatim and Khan Arzu along with other Delhi poets obsessed with ambiguity composed marsias, it was Mirza Rafi Sauda (1713-1780) who established this genre by composing it in the musaddas (6-live stanza) form.

Since then, this form has been the standard for marsia. Add-ons of the Indian cultural ethos to this genre was another one of Sauda’s innovations. After Deccan and Delhi, marsia moved to Lucknow where it not only witnessed an ascension to unprecedented popularity but also became a quintessential part of the literary/cultural life of the city. It was in these days that Mir Anis and Mirza Dabeer emerged as the two giants of marsia. Anis is rightly regarded as the fourth great Urdu poet, with Mir, Ghalib and Iqbal.

Marsia has not been a genre for male Muslim poets alone. In his book Urdu Marsiay ka Safar (History of Urdu elegy), Syed Ashoor Kazmi has mentioned the names of at least 17 Hindu poets who wrote marsia. Among the poets who contributed, there were some Hindu poets as well, such as Maharaja Kishan Parshad, Kali Das Gupta Raza and Jagan Nath Azaad. Kazmi has added brief notes on marsias written by women poets too, including Malka-e-Zamani (wife of Naseeruddin Hayder), Askari Khatoon and Razia Begum Riazat.

The tragedy of Karbala has metamorphosed into a huge symbol having religious, cultural, political and aesthetic dimensions. We can say that the singularity associated with the historical narrative of Karbala has given way to the fluidity in its meaning over time. It is not only a heart wrenching part of the Islamic history, it is also a ‘spatial thought’ that provides multiple ways to challenge the authorities tainted by illegitimacy. This ‘spatial thought’ seems to have come into play during the colonial and postcolonial regimes. This is evident in the elegiac poetry of the modern and the progressive Urdu poets of the early 20th century. Josh Malihabadi’s assertion that it is more important to understand the Hussain’s determination than lamenting the tragedy was made in the backdrop of the freedom movement against the colonial rulers.

Azm-i-Hussain (determination of Hussain) can provide a huge enough drive to bring about a revolution. This was the main theme of Malihabadi’s Marsia Hussain and Inqalab (Hussain and Revolution). Written in 1941, it merits to be declared one of the best modern, progressive marsias. As Syed Aale Raza, the first Pakistani marsia poet famously avowed, Karbala khitta-arzi ka faqat naam nahi (Karbala is not just the name of a piece of land), it embraces much more. Karbala is clearly a symbol. Symbols do not only outdo reality -- formed by the perception of the ‘now and this’-- they also create a continuum of a higher notion of reality. How Karbala provided impetus to the anticolonial movement as a symbol has not been analysed adequately. It would not be an exaggeration to assert that much of the modern marsia is rooted in the anticolonial thought.

While it is true that urdu marsia can probably not have another Mir Anis, yet it has continued its journey. Post-partition, most marsia poets settled in Pakistan. Josh, Ale Raza, Nasim Amrohvi, Najam Afandi, Raja Sahib Mahmood Abad, Saba Akbar Abadi and others chose to live in Karachi. As for marsia, Karachi undoubtedly emerged as the new cultural metropolis after Lucknow. In this regard, names of Saba Lucknavi, Raghib Muradabadi, Jamil Naqvi, Hilal Naqvi, Qamar Jalalvi, Umeed Fazli, Talib Johari must be mentioned. Among other Pakistani poets of this genre, works of Safdar Hussain, Waheedul Hasan Hashmi, Saif Zulfi, Johar Nizami and Mohsin Naqvi are remarkable.

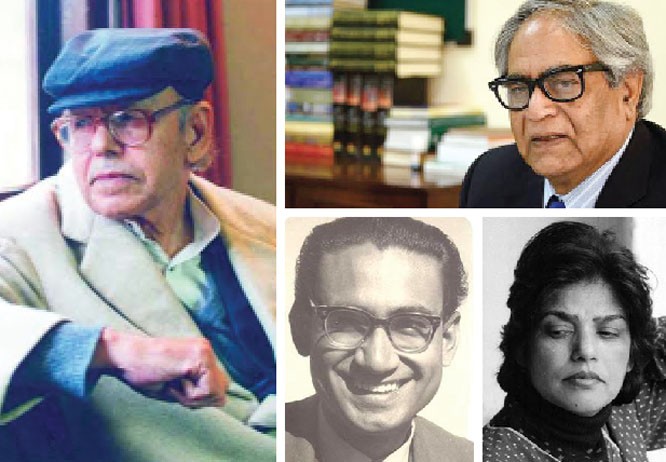

Apart from becoming the central theme of the marsia genre, the tragedy of Karbala has made inroads into Urdu ghazal and nazm too. This way marsia has sought to constitute an integral part of the overall poetics of modern Urdu poetry. Most of the marsias remain limited to the Azaadari/Majaalis in Muharram, but its presence can now be felt across Urdu poetry and across time as well. In Saniha i Karbala Bator She’ri Iste’ara (Tragedy of Karbala as a poetic metaphor), Gopi Chand Narang strives to discover how this tragedy gradually turned into a poetic metaphor and forayed into urdu poetry in multiple guises. A metaphor is limited whereas a symbol has a kind of breadth. Gopi Chand Narang traces multiple dimensions of the metaphor of Karbala into the poetic works of Majeed Amjad, Munir Niazi, Mustafi Zaidi, Jafar Tahir, Ahmad Faraz, Kishwar Naheed and Iftikhar Arif. In this respect names of Akhtar Hussain Jafri and Wazir Agha must also be mentioned. Sar (head), neza (spear), shaam (evening), sehra (desert), sajda (prostration), pias (thirst), alam (ensign), darya (river), dhoka (deceit), qurbani (sacrifice) are just some of the examples of words that allude to the tragic history of Karbala and can be found abundantly in modern and post-modern Urdu poetry.

It would not be impertinent to quote some verses that carry another dimension of the symbol of Karbala.

[Salute to those who refused to bow down to the fear of sword but surrendered to consent of God] [It is the same thirst, the same desert and the same family (of Imam Hussain); this relationship between an arrow and a small water skin is quite old] [The news just broke that this is the night that I’ll be assassinated; where are my brothers and friends]

The writer is a Lahore-based critic, short story writer and author of Urdu Adab ki Tashkeel-i-Jadid, Nazm Kaisay Parhhain (criticism) and Rakh Say Likhi Gai Kitab (short stories)