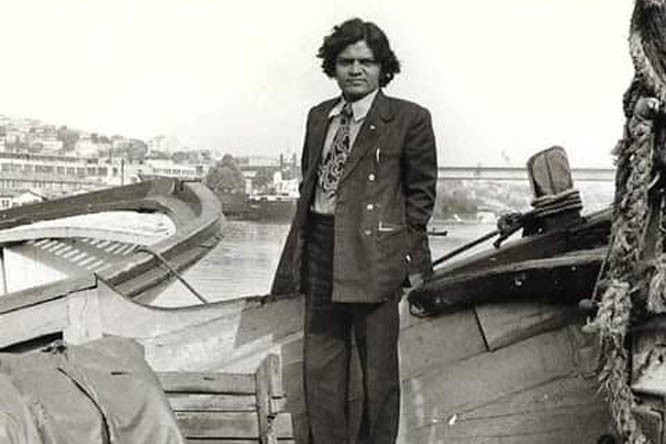

Painter and conservationist Dr Ajaz Anwar recalls fine arts classes at GC that were held in open air, his first painting; and, of course, his activism to protect Lahore, and the battles to be fought, lost and sometimes won

GC is still the only boys’ college that offers fine arts. The subject was newly introduced there, courtesy Dr Nazir Ahmad, the legendary principal. Aslam Minhas was newly appointed. He merits a separate chapter. He was appointed a lecturer and retired a lecturer. He never complained, because people of that stature are above worldly labels. Minhas Art Gallery, named after him, is testimony to his services to art.

Evening art classes at Alhamra (the name was suggested by Chughtai, who also designed its logo) were conducted by Prof Anna Molka Ahmad (wife of Sheikh Ahmad who designed the flag of Azad Kashmir), Khalid Iqbal, Colin David, and Nasim Hafeez Qazi. There was no age limit. Taufiq Aijaz conducted sculpture classes. Aslam Minhas schooled children on Sundays.

Classes at GC were very enlightening. Fine arts classes were held in a large room beneath the "Down" stairs. It was a sort of a common room for many literary personalities including Jojo, Qayyum Nazar, RA Khan, my own uncle Irshad Ali, Khalid Aftab, AD Kaleem, Rauf Anjum, and Mirza Munawwar. Sometimes Dr Nazir too would join us. Each of us five students was given a key to come and work in our free hours, and even during holidays. Lectures were relaxed and open to discussion and questions. Art classes were generally held in the open. On one such landscape excursion we were taken to the Walled City via Urdu Bazaar where I painted my first cityscape that has remained a passion with me ever since.

One life would not suffice to document Lahore. In fact, it is teamwork through photography, poetry, novels, short stories, music, folklore, oral history, performing arts, street performers plying snakes, monkeys and goats; ‘Sandows’ retired from circuses, wisdom shared by fakirs, paanwalas, teahouse waiters, tongawalas, schoolmasters, putliwalas, spin doctors selling spurious drugs and sanyasis selling tiger and lion fat, and even scorpion fat and brown bear bile; or the palmists oblivious to their own fate.

Parrots could also foretell events. When a fortune teller approached me, I spurned his offer, "Badshah aadami, toon saadi qadar naeen keeti!" He was trying to sell me a giddarr singhi (special charm). All this is Lahore. Too complex and complicated, yet an open book, revealing open secrets. Lahore being thousands of years old, a city of World Heritage status, is a platinum mine of subjects of interests for all creative minds. The tourists who frequented here during the 1970s, whom I met abroad, were full of praises for the city and its hospitality. Many painters have taken fancy to it. So have some playwrights and poets and songwriters. Many may have visited Lahore and died, but coming to Lahore is a re-incarnation, I once wrote.

My doctoral thesis guide at Istanbul Technical University, Professor Dr Dogan Kuban and, later, Sir Bernard Feilden at the International Centre for Conservation, UNESCO, Rome, could have been instrumental for me to stay back, but I wanted to return to the city of my passion. In this context, a singular blessing/achievement was the formation of the Lahore Conservation Society, convened by architect and town planner, Khwaja Zaheeruddin. It gave me an opportunity to write many articles in The Pakistan Times, graciously accepted by its magazine editor, Sarwar Shah.

In an attempt to save Lahore, the Punjab Special Premises Preservation Ordinance was passed in 1985. A list for protected buildings was also approved. Tollinton Market mysteriously disappeared from the list. When the then chief minister of the Punjab Pervez Elahi inaugurated my exhibition in the newly restored building, he promised to find it protection through the provincial assembly. Such action is still awaited.

Tollinton was singularly a success story. I advised against going to courts. As they planned to build an 11-storey plaza in this educational precinct, they applied for a bank loan. We learnt that this land had no ownership title. The khasra number was 420!

Public protests and the press was the strategy. And it worked. The usurpers gave up. The Exhibition Hall was saved, and restored and reopened as the Lahore Heritage Museum and this scribe’s solo show depicting Lahore cityscapes was held here.

Haveli Lakhe Shah could not be saved due to some Trojan horses. As I proudly led the Asian Study Group members, donkeys were seen removing debris. It is not the most important thing to win, it is more important to give a good fight, and we had done that.

There were more battles to be fought, both lost and won. The pedestrian bridge built in front of Chauburji marred its view. When they proposed to build such a bridge in front of York Cathedral, my teacher Sir Feilden had said, if you build that bridge, I shall leave York. It worked, but we are a different -- or rather an indifferent -- society. However, the bridge cutting the view of Chauburji was taken down! A roundabout suggested by myself was built around it, albeit much smaller and without the suggested pedestrian crossings that would have accommodated shops for the displaced encroachers. The plan was altered only to save the Anti-Corruption office built illegally.

Also read: "Lahore has been my city ever since" -- III

The shrine of Sheikh Musa Ahangar, on McLeod Road, the earliest monument in original condition whose graveyard area some group wanted to encroach upon, was successfully rescued. LCS’s founding members held a monthly meeting every last Wednesday. Slide shows were held with lectures and discussions.

Vigilant young volunteers are an asset for any organisation. Encroachments around Jehangir’s Tomb were pointed out. Sponsors were again local goons in the garb of MNAs. Shalamar is another story.

The Metro Bus that sacrificed countless trees and houses was not contested by the civil society; hence, the Orange Train blitz came on. Most of the city was turned into a newly excavated site. Countless people were left homeless. The bright idea of seeking relief from the courts worked initially but after having won in the High Court, everything was lost in the Supreme Court. The same happened to the signal-free corridor where numerous driving test-like U-turns were built depriving the pedestrians of the right to cross. Hospital data need to be studied for accidents thus caused.

To be concluded