A study of two stories on Kashmir written by Manto, depicting how in Pakistan and India the notion of a nation is so deeply embedded in religion

Fact and fiction are often represented as two distinct and mutually exclusive categories. It is believed that the world of facts tends to remain within the boundaries drawn by our senses while the world of fiction resists all attempts to impose limits upon it. While it is true that freedom is the hallmark of imagination, it cannot utterly disconnect itself from the world of reality and build an absolutely new realm.

Absolute autonomy of the imagination is a dream. What imagination captures is ultimately related - though in a queer manner - to the world of reality. Imagined stories bear traces of things or events experienced in the past, of ideas and beliefs inherited from family, or inculcated by social and state institutions. Some of the best works of fiction seem to lay emphasis on the fact that imagination goes on unravelling the ultimate limits of reality or probabilities. Social and political institutions incessantly seek to enforce limits on reality by imposing censors and conformist interpretive models. Hence, creative writers have an inherent urge on one hand to challenge the ways of representing a reality and on the other hand to probe all the probabilities ensuing from that reality.

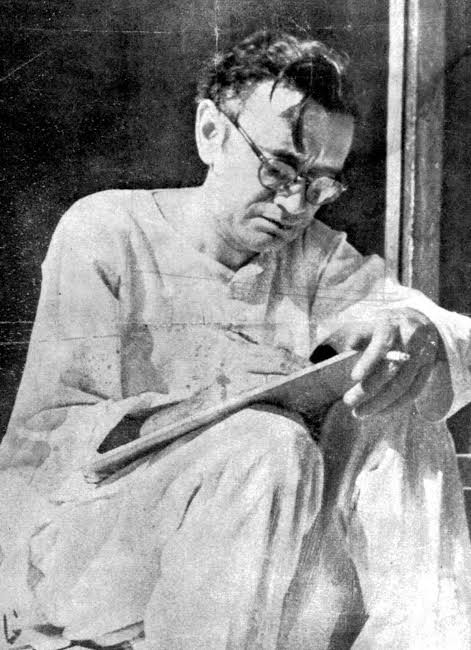

The art of fiction Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1954) developed over the years investigates political facts and their modes of representation, and ways of dispensation to speculate on the ultimate course they would probably take in the future. Fourth volume of Poora Manto, edited by Shams al Haq Usmani, recently published by Oxford University Press (OUP) includes two short stories on one of the hottest issues of today: Kashmir. One is Akhri Salute (The Last Salute) and the other one Tetval Ka Kutta (The Dog from Tetval).

These stories were written in the month of October (1951), presumably to commemorate -- in a Mantoesque way -- the first war on Kashmir which erupted in October 1947 - soon after India and Pakistan came into existence. The war set the tone of relations, the two countries were eventually going to develop in due course of time. What we see today with regard to Kashmir appears to be a later episode of the story begun in October 1947. The situation was astutely recaptured four years later by Manto.

Wars between nations have always been catastrophic, and not just economically. They show how desperately we fail to govern our death instinct. Furthermore, wars have brought us face to face with some grave existential and ethical questions. The Last Salute raises some basic yet baffling questions which still seem to prick the conscience of both countries.

Why did this war break out so soon after independence? Was it by chance or by design that the first thing the newly-born nations learnt was the language of war and enmity? Why was it that Muslim, Hindu and Sikh sepoys who fought against a common enemy in the World War Two (WWII) were made to hold rifles against each other? Rab Nawaz of The Last Salute asks the most intricate political and ethical questions in his monologue.

"Sometimes it all seemed like images in a dream: the declaration of the last World War, enlistment, the usual physical tests, target practice, being packed off to the front and moved from one theatre of war to another, and, finally, the end of war. And close upon its heels the creation of Pakistan, followed immediately by the Kashmir war - so many events occurring in dizzying succession. Could it be that all this was done to confuse people, to prevent them from taking the time to grasp it all? Why else would all these momentous events occur so rapidly that it makes your head spin?" (Translated by M Umar Memon)

The question, "Could it be that all this was done to confuse people"? resonates even today. What Manto wrote in Urdu couldn’t have been translated into English.

ربManto’s Subedar Rab Nawaz believes that all that happened was made to happen after thorough, strategic deliberations. He avoids saying who did this but emphasises that it was done mainly to confound people so that they shouldn’t comprehend the nature and course of events. It was a deadly game of distraction, confusion and disorder -- political, moral and existential. Rab Nawaz knew that they were fighting for Kashmir. He also believed that annexing of Kashmir was vital for the survival of Pakistan but when he spotted some familiar faces his confusion returned and he forgot the purpose of the battle. How dare he aim at Ram Singh, his one-time friend and neighbour. They had fought against a common enemy in WWII. Though these questions only add to his confusion and misery, he keeps raising them. Look at another set of questions, equally baffling, that the protagonist of the story raises.

"Were Pakistanis fighting for Kashmir or for Kashmiri Muslims? If the latter, why not also fight for the Muslims of Hyderabad and Junagarh? And if this was purely a war for Islam, why weren’t other Muslim countries fighting alongside them?" (Translated by M Umar Memon)

The questions are still valid. The lack of support from most Muslim countries for Kashmir is a fact that still disturbs many a sensitive soul. So what forms the core of our narrative on Kashmir? Is our focus on the land (with its resources and geographic-strategic significance) or on its people (with their religious, linguistic identity)? The story ends with the death of Ram Singh who is unintentionally shot by Rab Nawaz. But before dying he puts a question to Rab Nawaz, the most critical one in the story:

"Yaar, tell me honestly, do you people really want Kashmir?"

Rub Nawaz replies in all earnestness, "Yes, Ram Singha, we do."

"No, no, I can’t believe it. You’ve been taken for a ride." (Translated by M Umar Memon)

The question asked 68 years ago is still hovering over our political conscience.

In The Last Salute, Manto’s imagination set out to explore the course the Kashmir issue was to take in the future. He mastered the art of investigating real world problems by creating imagined issues. In Tetval Ka Kutta, Manto’s imagination stretches the reality of religion-based identity to its extreme limit(s). Religion claims to cover every aspect of human existence, so it doesn’t seem implausible to think that religion-based nationalism will seek to take every perceivable thing related to people, their culture and land into its fold. The story is again set in the war-torn Kashmir. Pakistani and Indian armies are ready to face each other on the mountain of Tetval. When a stray dog appears. Bored and exhausted sepoys start trifling with it. Harnam Singh, an Indian sepoy, throwing a biscuit at it says: wait, you are not Pakistani? On hearing this, a young soldier whispers:

"Now the dogs, too, have to acquire national identity: they will have to decide whether they would like to become Pakistani or Indian?"

So, Manto puts forward ironically how problematic the notion of a nation embedded deeply into religion is. The dog is straying on its homeland, Tetwal. He is in search of food and company. It is quite unaware of the birth of two nations in the name of religion and unmindful of the fact that his homeland and its inhabitants have taken on new identities, sacred or profane. It is destined to be killed by army personnel who only know the language of hate and aggression. Both these short stories put a serious question to those in power: when will they stop trifling with the miseries of Kashmiri people?