What does it mean to be a woman in a public space in Pakistan?

This year the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government made it mandatory for school girls to wear burqas. The notification issued in Peshawar stated that the decision was made in order to protect women from "unethical incidents". The notification was eventually retracted due to public scrutiny. However, this did not stop a local leader in Mardan from distributing burqas "free of cost" among government school students. Forced veiling has been protested, and rightfully so, but apart from highlighting problematic regulation, I want to question our political vocabulary.

What does a notification mean when it suggests that it seeks to protect women from unethical incidents? "Unethical" is purposefully impersonal. It situates trauma upon our bodies as disruption of social values. These values are not disrupted when women are subjected to "unethical incidents" - rape, assault and harassment. These values are disrupted when we come forward. We are cross-examined in our failure to protect ourselves. What were we wearing? Who were we with? How dare we occupy public spaces in a patriarchal nation? The trauma upon our bodies is irrelevant. In actuality, the "unethical incident" is us coming forward.

What do they mean when they say "free of cost"? Such a distribution invariably has its price. Ask women who pay for "free distribution" simply by existing in public spaces - we pay for it in our emotional labour. We pay for it in knowing that the responsibility for being safe is placed entirely on our bodies. We pay for it in the understanding that we are not safe even if we leave our homes wearing armour.

What does it mean to be a woman in a public space in Pakistan? I receive a variety of answers to this question. What all the answers have in common is that the focus remains on correct behaviour required from women. There is self-righteous condemnation. Women need to be a symbol of Pakistaniyat - nationality should reflect in how they dress and how they act. There are people who insist that women should toughen up, that perhaps fear is representative of privilege. There are women who live in worse conditions, who do not have time to fear because they have to worry about feeding their families. While patriarchy is intersectional and class-based, these two concepts are conflated in order to distract, and to not hold men responsible. It is always the woman who will be blamed: at times it is her class, her promiscuous nature or her lack of Pakistaniyat. It is never the man. To blame patriarchy on men is reductive, so let us continue to blame women. Qandeel Baloch did not come from privilege. She was murdered because she refused to oblige to national regulation. Even as the nation mourns her death, they insist that her behaviour is symbolic of misdirected women who need saving. The pressure on women to fear consequences of being "unethical" spares no one.

Also read: Editorial

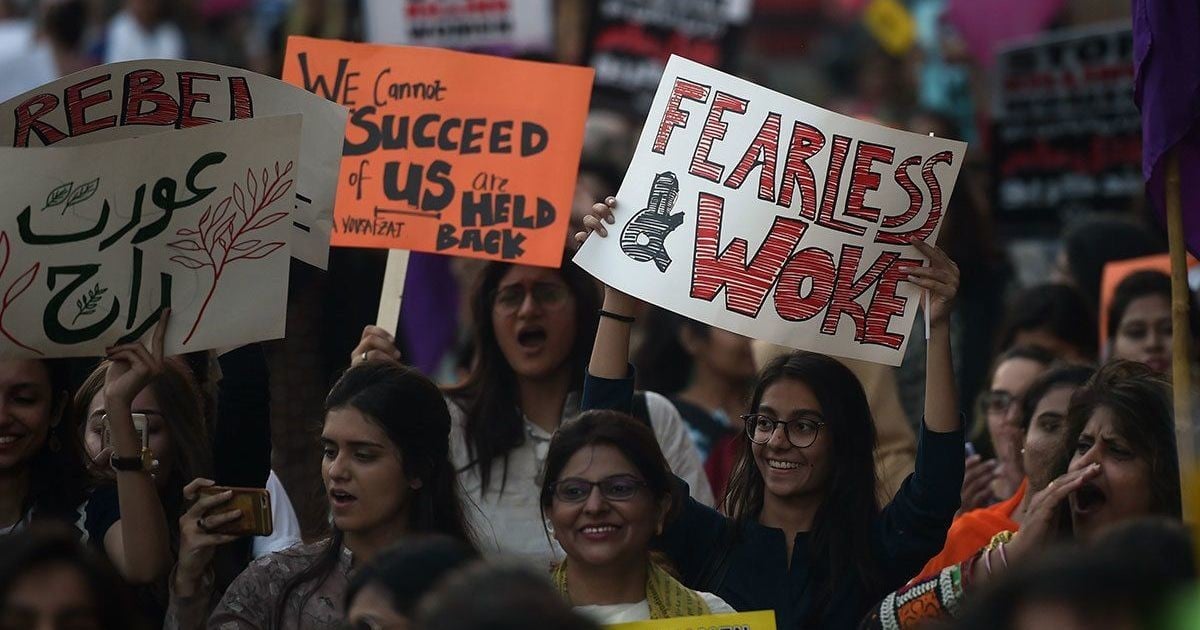

The Aurat March is an organised protest to observe international women’s day. This protest brings together women from class backgrounds, the transgender and the queer community. The protest is a celebration of difference and reclamation of public spaces. Every year it incites communal rage. There are no rational grounds for opposing this march. There is reliance on vague accusations such as the protest having a "western agenda" or not being representative of true Pakistani values. These accusations are effective - they do not require evidence in order to instigate spectacles against women (such as the mard march). Critics of Aurat March rely on vague accusations to disguise and intellectualise how they are simply offended by women and the queer community occupying public spaces on their own terms.

What does it mean to be a woman in a public space in Pakistan? It is political - we occupy public spaces in the form of resistance. There are women who participate in patriarchal norms. There are women who are not aware that the pressure they face is not their burden to carry. There are women who share this awareness, and they are furious. Every time we occupy public spaces, no matter where we come from, it is always political. We are all familiar with fear. We are taught to protect ourselves in order to manage this fear.

What does it mean to be a woman in a public space in Pakistan? This question needs to be re-directed. We need answers from men: leaders who fail to contextualise our gendered politics; men who equate parenting of daughters with control; husbands and partners who claim to protect us but are really protecting their ego; men who touch us without our consent, who rape and murder. We need answers from a system which fails to hold men accountable for their actions.