Given the fact that about 10 percent of the youth in Pakistan are unemployed and have no vocational or technical skills, a proactive strategy to address the problem is needed

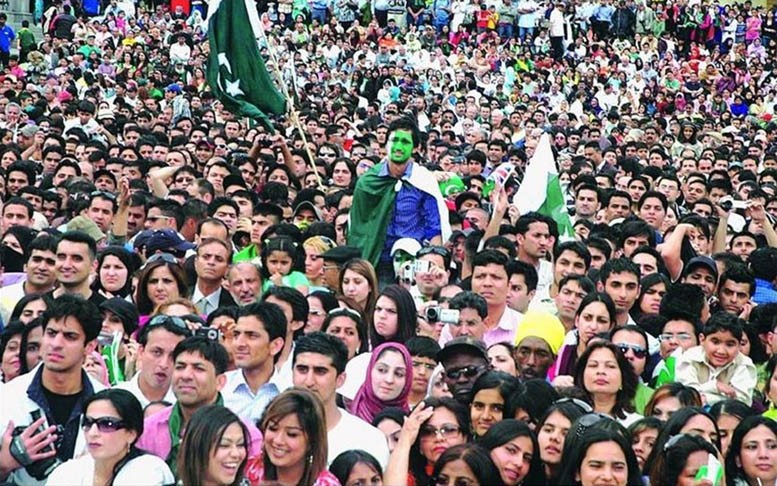

Pakistan has an exceptional asset in the shape of youth bulge, which means that the largest segment of our population consists of young people (64 percent of the population is below 30). Pakistan is the second youngest country in South Asia after Afghanistan and one of the youngest countries in the world. The youth bulge can translate into economic gains only if the youth have skills consistent with the requirements of a modern economy.

If this demographic asset is not harnessed, it can become a major crisis of unemployment. About three million young people enter the job market in Pakistan every year. As economies around the world undergo structural changes, traditional skills become increasingly irrelevant.

Given the fact that almost 10 percent of the youth in Pakistan are already unemployed and have no vocational or technical skills, a proactive strategy to address the problem of unemployment is needed urgently.

Problems of Pakistan’s labour-force are two-fold. First, Pakistan has a very high illiteracy rate. According to the 2018 census, 38 percent of Pakistanis at 10 and above are illiterate. The second problem is no less intriguing because it involves inefficiency. Most of the graduates joining the labour force, with the exception of a few with professional degrees, are trained in general education, which is often not consistent with the requirements of the job market.

Though the information available in this regard is patchy, one estimate suggests that only 8 percent of the enrollment in tertiary education is in medical and engineering domains, while a whopping 33 percent of the enrollment is in arts and humanities.

This situation is in sharp contrast to the requirements of the job market -- both nationally and internationally. The trending jobs all over the world are in healthcare, data sciences, and engineering. However, Pakistan has a very limited capacity to produce quality healthcare professionals. Punjab, the largest province of Pakistan with 110 million population, has just 3,400 seats for MBBS in a year, which translates into producing three doctors for 100,000 people every year.

In Pakistan, little change in the age-old educational patterns is symptomatic of a deeper malaise: inability to learn the best practices and to adapt to the changes. A fresh graduate with a degree in arts or a degree in languages has very limited options to find gainful employment, except in the education sector. Even if the education sector is expanding, it is still not capable of absorbing all the new entrants in the labour market. A large number of highly qualified young people working for ride-hailing taxi services in the metropolitan cities points to the changing dynamics of the labour market.

Though there can be no gainsaying the fact that education in the domain of arts and humanities is crucial for cultivating positive social norms, the production of a large number of graduates with skill sets which are irrelevant to the market requirement is the last thing we can afford. One is hard-pressed to figure out job’s consistent with the skill set of a fresh college graduate.

The answer to the problem of irrelevant education seems to lie in the promotion of vocational education after graduation from school. A focus on vocational education has the potential to boost the manufacturing sector and expand its export base. However, our attitude to this important window of opportunity is no less disconcerting.

The difference between the vocational education system in Pakistan and some developed countries is telling. More than one-third of all students who graduate from secondary school in Germany enter a vocational training programme and about 51 percent of the country’s workforce is trained in the vocational education system. Currently, there are around 200,000 students enrolled in the 3800 TEVTA institutes throughout Pakistan which is a minute fraction of 48 million total enrollment in Pakistan. Put differently, only four out of 1000 students are enrolled in the formal vocational institutions.

An emphasis in the schools, colleges, and universities on the development of entrepreneurial skills is an important step to capitalise on the youth bulge. A failure to benefit from this opportunity would mean that our population will become both aged and poor. The best practices suggest that the government needs to engage the private sector to ensure that the technical education being imparted in the vocational institutions as well as universities are relevant to the needs of the market. Incentivising the private sector to provide internships and training to the students could go a long way to make vocational education more relevant.

Ensuring the quality of vocational education is no less important. In this regard, Pakistan may learn from the experience of developed countries like Japan and Germany. These two countries transformed their economies after World War-II through a focus on technical and vocational education. Japan became a giant in the field of technology and one of the world’s leading economies by developing a skilled and trained workforce. Germany, the fourth-largest economy in the world today, prides itself on its vocational education system.

Increasing the share of vocational education requires a paradigm shift with a focus on changing the mindsets of the people regarding the job choices. It is true that one needs a sizable pool of experts with managerial skills, it is equally true that the economy is driven by skilled hands. The skill level of workers in the factories, agriculture sector, marketplaces, and construction sector determines the level of productivity of the economy. So the need of the hour is to develop state-of-the-art skills in these sectors.

The nature and quality of a job in Pakistan makes a big social statement. This may not have to be so. In many other countries, a boy is not stereotyped because he wants to become a cook in a restaurant or a firefighter. However, in Pakistan, there are only a few jobs that inspire the popular imagination. These dream jobs include being a doctor, engineer, computer scientist, civil servant or a banker. Interestingly, teaching is very often not the first priority of most students. Data sciences are on the radar of only a few students despite the fact that it is a highly rewarding domain.

The political narrative of the public-sector jobs needs to change in order to address the problem of unemployment. Pakistan has been following a policy on the public sector jobs that runs counter to the trends in many developed countries of the world. Traditionally, the public sector in many countries has been shrinking and there has been a focus on the expansion of the private sector. Governments, in the developed world, have been increasingly taking their hands off the subjects which were considered their prime responsibility, such as the provision of education and health services.

In Pakistan, government jobs are prized for their relative stability and security. However, there is a catch here. The public sector in Pakistan is a generous employer of middle to low-grade personnel and offers perks which are roughly double the rate offered by the private sector counterparts.

However, given the economic constraints of Pakistan, government cannot afford to offer its employees salaries which can attract the best talent. Consequently, the ratio of better-skilled individuals in the public sector employment is very small. According to the latest statistics, the number of federal government employees stands at 581,240 out of which only 5 percent are in the BSP 17-22. At the top tier, however, the government pay packages are a fraction of what leading multinationals pay to their senior management. So the public sector employment is the preferred choice of individuals with mediocre skill levels.

In the election season, the issue of public sector jobs is deliberately orchestrated to woo voters. The PTI promised 10 million jobs in its election manifesto. That this is never going to materialise is a foregone conclusion. Rather than offering low quality jobs with little chances of growth, which often trap the government employees in a vicious circle of poverty, the state should make clear its limitation to provide public sector jobs so that the younger generation adapts their job prospects accordingly.

The writer is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics, COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus and may be reached at rafi.amiruddin@gmail.com