Watching the flights of birds from her fifth-floor apartment in Lahore, she produces a cartography of that sojourn, keeping viewers guessing about their destination

Arthur C Danto in his essay on Mark Rothko mentions the tendency in American publications to juxtapose paintings of abstract expressionist artists with images from real life. For instance, Franz Kline’s "characteristic black forms, starkly composed against a white background, might be placed alongside a photograph of some industrial scaffolding, shown silhouetted against a light sky. A canvas of Jackson Pollock’s might be placed next to a photograph of tangled water weeds." Resemblance with an element in nature was thus necessary for abstract art to be accepted.

This illustrates a divide between nature and culture. Mankind is surrounded by - and part of - nature but it is human mind that has developed the unique form of geometric shapes. Perfect squares, circles and rectangles are not a naturally common occurrence. In a sense, the first people who devised these shapes were the actual pioneers of abstract art; as these shapes did not imitate an optical experience, rather they possessed a separate and independent form. Although these geometric shapes refer to sublime ideas and symbolic concepts, but in their visual manifestation did not represent a world that existed.

You may call it geometry, or abstraction, it is a means to tame nature into precision and balance; raw into refined; chaos into order; irregular into straight; spontaneity into planning. One example of this feat is the concept of a garden, where human expression transforms unruly nature, growing in every direction into a precise composition of mowed grass, flower beds, rows of trees and water channels. Most artists today are faced with an existential question: to follow a mimetic path or to rely on forms not encountered in nature?

There are other endeavours in the realm of geometric formulation in which nature is stripped down to its skeletal state such as creating patterns, making elementary motifs such as tantric or Muslim art; alongside constructing modern buildings with flat surfaces and designing products with minimalistic aesthetics.

It is also imperative to move beyond the widely accepted notion of abstract art, as an invention of the west. The works from mid 20th century New York can be challenged as the first wave of abstract art by presenting the expansive works of eastern tribal societies. Within the ancient cultural practices of African, pre-Columbian America and Asian art there is an overwhelming tendency for non-representational art. Yet in our present world, the western industrial nations are mostly associated with order and precision, while eastern agrarian economies are equated with disarray and unpredictability.

In her work Wardha Shabbir seems to be accepting these demarcations and refuting them at the same time. Her training in Indian miniature art at the National College of Art, Lahore, facilitated her denoting the world into an abstraction of patterns. However, instead of stark and flat shapes, these areas consist of identifiable forms. They are not a physical copy of what is observed through the eyes, an optical phenomenon, but a blend of observation and organisation, much like the world concocted in miniature painting, which is the synthesis of senses through an analytical exercise.

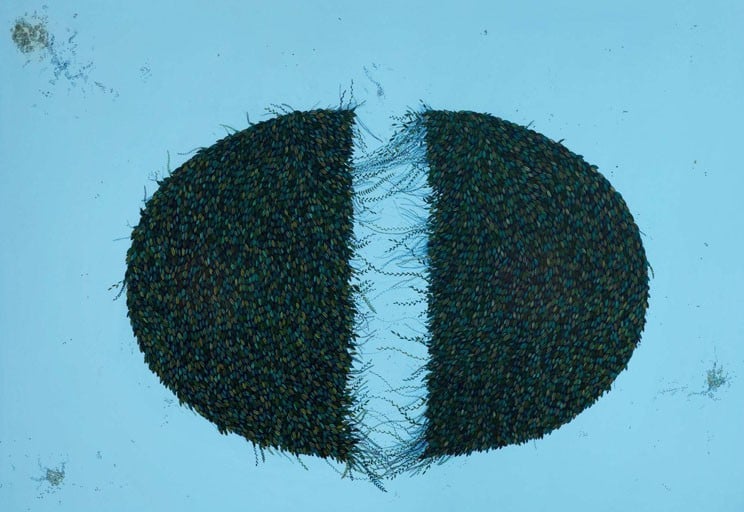

Drawing references from her earlier experience with miniature art, Shabbir is now venturing onto a different ‘path’. The word ‘path’ is used because her new works do seem like maps -- of locations as well as objects that are unknown and yet believable because of the precision in their conception. These geometric shapes or forms with sharp outlines are mainly containers of a growth of leaves and vegetation. You see this in her works on paper as well as in the three-dimensional pieces and installation -- all parts of her present solo exhibition In a Free State, at Grosvenor Gallery, London.

From a distance, some of these geometrical shapes appear to be ellipses, cubes or plinths, but these are modified, broken, open and diffused at their boundaries. In a sense, it is a growing geometry -- evolving, altering, expanding and bursting at the edges. For a viewer, the work offers parallels with Anish Kapoor, in whose work basic geometric forms are experienced as organic substances. This phenomenon is illustrated in Shabbir’s work as well. So a plinth is contracting in the middle of her works such as of a genre, or vertical bands of equal length and width end up sprouting stems at the top, a basic instinct, or a wall like shape is growing leaves at some points.

Her last work Map of mind, is significant -- almost a key to decipher her art, because here nature and culture, order and spontaneity, merge to produce a new pictorial solution. The specific image in this work is based upon the passage from the artist’s hotel in London to her gallery space. She has marked the map, but intriguingly renders it with two viewpoints. One section is portrayed as an ‘elevation’ while the other is drawn like a ‘plan’, without any indication of separating the two. Here, Shabbir recalls the pictorial system of miniature paintings, which centuries before cubism, incorporated multiple views within one picture frame, unlike the traditional European notion of a painting as a window into a space.

Interestingly, the surface of this work is not rectangular, circular, or square, but follows the layout of the main image within the work.

The other work of a similar sensibility is the path, but the rest of the exhibition indicates another way forward for Shabbir’s aesthetics. She picks geometrical shapes, only to bend and break them. A circular form is opened up with its slices rotating around an absent orbit in between states; shards of some structure are moving on an empty backdrop in coming together; or diagrams of different sorts are placed in a sequence on paper such as in a manuscript. Some of these are linked to her sculptures such as a narrative of space and a scripture of time; fabricated in resin and mixed media with leaves inside the transparent surface connecting to an important piece in the exhibit, a life cycle. Watching the flights of birds from her fifth-floor apartment in Lahore, Watching the flights of birds from her fifth-floor apartment in Lahore, she produces a cartography of that sojourn, keeping viewers guessing about their destination. Birds that look like leaves can sometimes be symbols of the artist’s self; in fact, self as an artist -- a person who was educated in miniature painting, produced works in that genre, but has always attempted to break the boundaries, by extending her imagery on gallery wall.

Being at Wardha Shabbir’s solo exhibition, one feels that like the leaves and birds, her new work is fluttering and flying, away from the definition and demarcation of tradition, technique, discipline and genre, and exists ‘in a free state’.

The exhibition is being held at Grosvenor Gallery London from September 26 to October 18, 2019