During the past decade, it has become clear that no corruption, real or perceived, will go uninvestigated. It’s Syed Khursheed Ahmed Shah this time. Who’ll be next? The future is not unimaginable

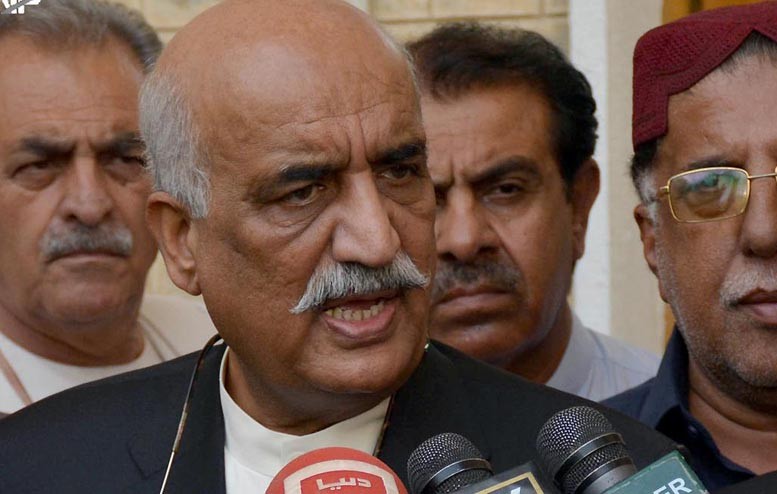

With the arrest of Syed Khursheed Ahmed Shah in Islamabad, another major leader of the Opposition is now behind bars.

It is pertinent to mention that several cases involving allegations of corruption against Shah have been investigated by the NAB earlier and closed because there was insufficient evidence to prosecute. In August, the NAB once again opened the cases and asked him to appear before its Sukkur establishment. Being in Islamabad, Shah excused himself and did not appear despite repeated summons. NAB-Sukkur then contacted the NAB chairman, Justice Javed Iqbal (retired), in this regard.

The chairman obtained approval from the NAB board and ordered his arrest. Ironically, Shah as Opposition leader in 2017 had agreed with the then prime minister, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, to appoint Justice Iqbal as NAB chairman. Now that the former PM and then Opposition leader have both been arrested, Abbasi has asked the nation to forgive him for approving this appointment.

The charges against Shah are broadly the same as against many other Opposition leaders. They include allegations of having assets beyond their declared income, and of possession of wealth that, according to NAB officials, cannot be justified.

Shah has been accused of owning petrol pumps, bungalows in various housing schemes and shares in some hotels. While it may be premature to comment on the quality of evidence against Shah, the perception of a selective accountability, targeting only the politicians belonging to the Opposition, is growing stronger.

The NAB chairman has been reported in the past as admitting that if corruption cases were initiated as readily against members of the ruling party, the government would be in serious danger. Historically, accountability has targeted Opposition politicians in Pakistan. This practice was started by our first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, and continued throughout the 1950s. With the promulgation of martial law in 1958, accountability took a new turn. In the 1950s, Elective Bodies Disqualification Ordinance (Ebdo) and Public Representatives Offices Disqualification Act (Proda) were frequently used against the Opposition.

Interestingly, as soon as some Opposition politicians joined the ruling party, most of these cases were either withdrawn or just left unpursued. A similar pattern was visible with the charges of treason. Anybody who did not fall in line was accused of being a traitor. A conspiracy to break up the country was then discovered. The examples are too many and too familiar to require citation. Thus Dr Khan Sahib was declared a traitor and put behind bars. After some years, however, he was appointed the first governor of the One-Unit West Pakistan (in 1955).

Ayub Khuhro is another shining example. He was charged with corruption but rehabilitated soon enough when he decided to support the One-Unit scheme. Maulvi Fazlul Haq, the Sher-i-Bengal, was declared a traitor in 1954 after he won an absolute majority in the provincial elections in East Bengal (later East Pakistan). He was accused of conspiring against the integrity of Pakistan and dismissed from the office of chief minister office despite having a huge majority in the assembly. This was done without moving a vote of no-confidence against him because such a vote could have been doomed to fail.

When General Ayub Khan assumed power after unceremoniously removing the first president of Pakistan, Iskandar Mirza, accountability became overtly conditional. It was openly announced that the politicians who quit politics voluntarily would be spared and those who didn’t, would face prosecution. Most politicians left the field; some including Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy didn’t and faced cases. Ayub Khan talked a lot about corruption but some people close to him were believed to have benefited during his tenure and became billionaires.

Both General Yahya Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto used the ‘traitor’ tag quite frequently. The entire Awami League, and in fact the whole Bengali population who voted for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, constituting 55 per cent of the population of Pakistan were declared traitors. ZA Bhutto, unable to accuse the NAP-JUI governments in Balochistan and the NWFP (now KP) of corruption, used the ‘treason’ card against them. The entire NAP leadership, including Wali Khan, Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo and Attaullah Mengal, was accused of conspiring against the state and trying to destabilise and break up the country.

The ‘traitors’ were released by General Ziaul Haq, who tried to use them against ZA Bhutto and the PPP. General Zia called the PPP corrupt, traitors and anti-Islam, trying even to create doubts about the Muslim origin of ZA Bhutto. White papers were released and TV programmes produced and broadcast, even as no there were no convictions.

The Muhammad Khan Junejo government, appointed by General Zia himself, was deemed too corrupt to continue beyond the three-year mark. Junejo had been handpicked by Zia who had all the confidence in him, but when the ‘elected’ PM started asserting himself, it suddenly dawned on General Zia that Junejo was corrupt and venal. However, no cases were brought against him and no move was made to present a ‘no-confidence’ motion against him.

When the Benazir Bhutto government came to power in 1988, she was considered too callow to handle ‘sensitive’ ministries like foreign affairs and finance.

In 20 months, she was sent packing on corruption charges, but none of the cases against her were proved. President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, who had been a blue-eyed boy of the deep state for decades, particularly hated and maligned Asif Ali Zardari. But when in 1993, his relations with his own protégé, Nawaz Sharif, were strained, he administered the oath of a caretaker minister to the same Asif Zardari, after removing Nawaz Sharif.

The 1990s saw the PML-N and the PPP accusing each other of corruption. None could achieve much apart from strengthening the Establishment and weakening the nascent Democracy.

An early form of the NAB emerged in the second government of Nawaz Sharif from 1997 to 1999, when Saifur Rehman was unleashed to get Asif Zardari, Benazir Bhutto, and other PPP leaders. Again the PML-N achieved nothing but shot itself in the foot and met its comeuppance in the form of the October 1999 coup mounted by General Pervez Musharraf. Under the new dictator, the accountability mantra was institutionalised and by General Amjad Ali Khan Khattak and General Aziz who both served as NAB chairmen in the 2000s.

The post-Musharraf period saw some respite for the politicians. However, the troika of accountability-corruption-politicians mantra had been so embedded in national polity that even being in the government was not an effective shield against it. During the past 10 years, it has become clear that no corruption, real or perceived, would go unnoticed and uninvestigated. The PTI leaders will do well to be ready for the next round. The future is not unimaginable.

But all this does not bode well for democracy, for politicians, and for politics per se. This is not to say that there should be no accountability or that corruption should be tolerated. The point is to make sure that the perception of selective accountability does not take hold. That can only be achieved by shunning high-handedness, and not sparing those who have been spared time and again.