Other than a poetic dimension, there is little of interest to failing at preparing a meal. After all, spices can’t conspire against you. Appliances don’t have minds of their own. Utensils aren’t your enemies. But, on a bad day, it seems that pots and pans can turn against you; and all that you keep and eat in this little factory can drive you to the edge.

These were foreign pots and pans. Maybe they could sense my uncertainty. I was in London in a kitchen without a pressure cooker. Imagine that. No whistles to beckon me, let me know that the food is ready.

"I yelled at the onions I burnt today," I told a friend over the phone.

"Well, you made good chickpea curry the other day. Maybe it’s just one of those days. Anyway, the hobs are funny. I can come over if it helps," she replied.

We got takeout and watched Brooklyn Nine-Nine. The evening became lighter and more bearable, thankfully. It took a few more to come to the realisation that knowing you can start over offers some respite. As many times as you like. Cooking for one changes things.

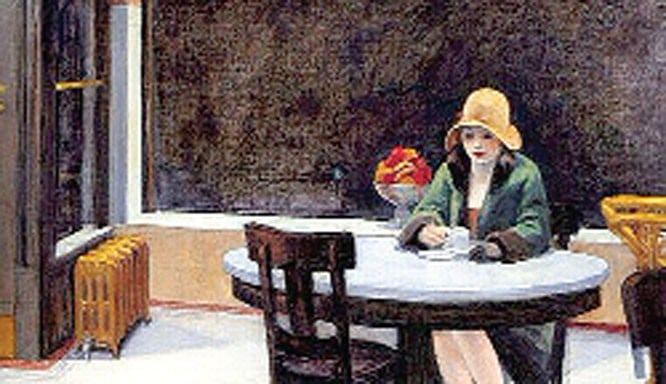

All embarrassments and victories are private. Being away from home for about two years, I read all sorts of meaning into preparing food. Somehow honouring the frailty of your life by cooking for yourself can feel strange. Like sending yourself a cheeky greeting card, and being unsure how to react when you finally receive it. To be fair, I hadn’t thought of food as something devoid of its social or communal aspect before.

I remembered how my grandmother and I would spend hours together in her kitchen as she cooked and hummed. As her smile lines deepened and her bones became softer, the pots and pans did turn on her. When they finally banished her from the kitchen, things did change. Nevertheless, we ate together with the same excitement; waiting, like always, for all the seats at the dining table to be filled with family members. She would insist that we wait until everyone was there so we could start together. Food was metaphor first to her, and to those I grew up around.

Cooking for someone else, in a context devoid of patriarchal violence, perhaps, would be less heavy in its symbolism. Imagine it being merely a compliment, an act of care without the baggage that it brings. Perhaps, there is also something to be said of turning all that love and concern towards yourself as you reconcile with solitude, realising that you forge respite out of chaos at every stage.

You dice the eggplant. You split the pea pods open. You crack the eggs. Out of this chaos, you create something new and beautiful that with every bite will be broken down into a mesh of flavours and sensations.

My sister often calls or messages me now, asking for easy dorm-room microwave recipes. My mother and I send long voice notes, giving detailed instructions, improvising recipes to suit what ingredients she would find readily available. When we eat a delicious meal, we wonder out loud what she might be making in her kitchen thousands of miles away.

"She’s probably making pasta with pesto or eating hummus with flat-bread if she’s had a long day," I say.

Secretly, I wonder if she is becoming a more adventurous cook like I was briefly; standing in her "kitchen with an eggplant" trying to recall what she saw on a Tastemade video.

I’ll send her a link anyway. In case the pots and pans are being rude today.