It is time to revive Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s political ideas and ideals to make Pakistan a strong and a true federal state

A section in the Pakistani society sees Abdul Ghaffar Khan as that anti-Pakistan Pakhtun nationalist who preferred to be buried in Afghanistan. He is remembered as a racist, ethnicity-driven diehard and a close comrade of Gandhi, Nehru and other leaders of the Indian National Congress. Unfortunately, he has often been dubbed as a traitor for opposing the creation of Pakistan; and then allegedly working to undermine its federal democratic disposition.

Ironically, even among Pakhtun nationalists, he is mainly remembered as the harbinger of the struggle for an independent Pakhtun state, which he demanded at the time of partition in 1947. Many of his followers proudly own the title, ‘Frontier Gandhi’, that was given to him by Congress during the pre-partition days.

Very few of them, however, took the pain to try and bring about his ideals and his true political orientation before the world. Most scholars have largely been sticking to a traditionalist view regarding his effort and role during the pre and post-partition periods.

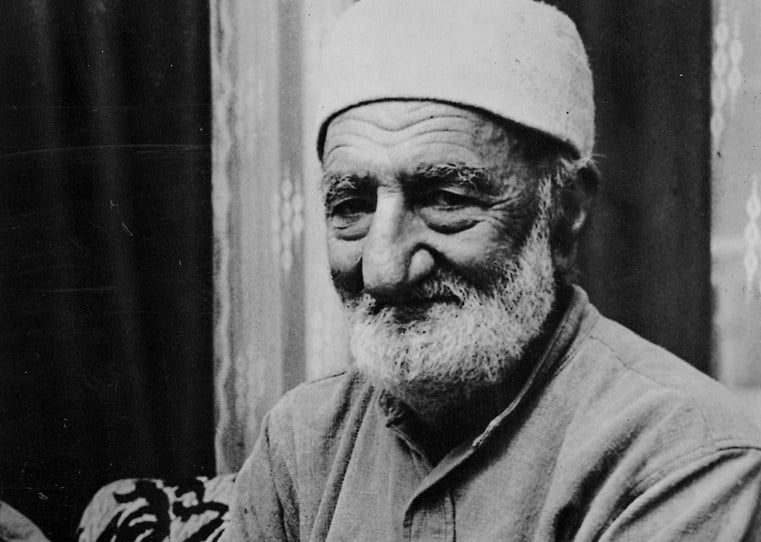

From the very start of his emergence as a popular leader, Khan was a lifelong pacifist and humanist. He advocated serving the downtrodden sections, charity and support for the needy, non-violence and wellbeing of poor people. His sole objective was to serve his people and bring about radical reforms in society.

Khan ruled the hearts of people and received honorific titles such as Fakhr-i-Afghan (Pride of the Pakhtuns) and Bacha Khan (King Khan).

He had an unwavering faith in the non-compatibility of Islam and violence. He would deliver speeches from the pulpit, which turned a number of anti-British ulema into his most sincere allies. His religious views were progressive even before he’d ventured into politics but carved within the cultural parameters of the Pakhtunwali. He struggled for the rights of women, children and other oppressed groups, which made him quite popular among the masses.

His progressive approach in politics, anti-British stance, people-friendly orientations and a cross-communal claim brought him close to the Congress leaders who at that time were eager to enlist Khudai Khidmatgars’ support for strengthening their party’s position in the province.

Two things are important regarding his relations with Congress and Gandhi. Firstly, it is a general perception that Khan adopted his stance on non-violence and tolerance from Gandhi. However, this has mostly been claimed by Indian scholars and is untenable according to the available sources. Prof Syed Wiqar Ali Shah has mentioned that it was much before his sojourns with Gandhi and Congress that Khan started campaigning against British brutality.

In his book Nonviolent Soldier of Islam, Eknath Easwaran says that no one was more aware than Khan of the huge price Pakhtuns were paying for their infatuation with violence. He further says that they had been dispossessed of their freedom only because of their own self-destructive tendencies. Technically, it was closer to the idea of non-violence or ahimsa propagated by Gandhi. However, Gandhi employed the idea to manoeuvre the Indian political scene in his favour whereas Khan utilised it to pacify the war-hungry Pakhtuns. Secondly, some authors argue that after meeting with Gandhi, Khan adopted a simple lifestyle just to attract the masses. Again, this claim seems untenable as Khan never had a luxurious lifestyle. Congress leaders were well aware of the charismatic manifestation of Khan, and how it could be utilised to penetrate Congress’s message among the masses in the frontier. It was due to these reasons that Congress gave him the title of ‘Frontier Gandhi’; to portray him as a subordinate to Gandhi. However, Hindu leaders did fear that Bacha Khan’s powerful personality would outgrow Gandhi’s.

Practically speaking, Congress achieved a huge victory by enlisting the services of Khudai Khidmatgars in the frontier province. But in that political bargain, the Khudai Khidmatgars took very little in return.

Khan’s association with the Congress trivialises his actual charismatic standing. In reality, striving for democratic rights, selfless social service, a struggle for reforms and peaceful coexistence made him one of the most influential leaders in the Indian political arena. He did not need Gandhi or Congress to spread his message. His views were sophisticated and ahead of the times. Gandhi adopted these elements as his political techniques whereas Khan gradually inculcated these in the minds of his followers. He was more than a mere politician. He was the harbinger of change.

A disadvantage of merging his movement with that of Congress’s was that some of his ideas allegedly got hijacked by Gandhi, who, on several occasions, called him as his ‘staunchest’ follower. It has been argued that the title ‘Frontier Gandhi’ could have very well been a part of Congress’s strategy to limit the scope of Khan’s politics to a particular ethnic group. In fact, Gandhi skilfully exploited the support which the great Khan enjoyed among Pakhtuns. When Congress and Gandhi accepted the June 3 plan Khan was not even consulted. He expressed his disapproval in clear terms in front of Gandhi.

Post-partition, he continued to take part in social and political activities and was arrested on a number of times on false charges. It is generally perceived in Pakistan that he had extra-territorial loyalties and his rhetoric was anti-Pakistani, a fact that was allegedly propagandist and was never proved in court. Right until the 1970s, he was persecuted by every government. This was despite his post-partition belief in keeping the federal structure of Pakistan intact.

Not a single statement of Khan is available that could be termed as anti-Pakistani after August 14, 1947. But to understand why he was labelled as a threat to national integration, we will have to understand his struggle post-1947.

Khan was initially against the partition of the subcontinent, instead, he dreamed of creating a united, independent and secular India. Like many Pakistani politicians, the partition of India in 1947 caused him great distress but after the partition, he never made a single anti-Pakistani statement. He channelised the Pakhtuns’ political orientation within the federal and constitutional framework of Pakistan.

He had a firm belief in the federation of Pakistan which he expressed several times on the floor of Assembly. His only demand was to rename the NWFP as Pukhtunistan since the former was a geographical name for the region given by the British. He was also due to meet Muhammad Ali Jinnah in this regard - a meeting that never took place. Just before the two were scheduled to meet, Khan was arrested and subsequently subjected to severe brutality in solitary confinement. It was later argued that his arrest was necessary for the political survival of certain League leaders and to keep him away from mainstream politics.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan made a considerable effort to solve the Kashmir dispute in the initial days. Javed Ahmad Siddiqui mentions in his book Abdul Ghaffar Khan: Ghaddar ya Muhhib-i-Watan that the Kashmir problem could easily be solved at the time of partition, but not a single Pakistani leader tried to approach Shaikh Abdullah who was already inclined towards Pakistan. This indifferent attitude on the part of Pakistani leaders subsequently complicated the problem.

Bacha Khan took a number of steps to strengthen the federal structure of the nascent state of Pakistan. In the Constituent Assembly, he urged his colleagues to work hard to make Pakistan a true welfare state. He actively took part in the formation of national level progressive and leftist parties. His memorable role in the creation of Pakistan National Party (1956) and National Awami Party (1957) has vividly been described by Abdul Wali Khan in his Pashto book, Bacha Khan aw Khudai Khidmatgari. It was none other than Bacha Khan who came up with the name of Fatima Jinnah as a prospective candidate from the Combined Opposition Parties (COP) to contest the presidential election against Ayub Khan in 1964.

In order to keep him away from forming an alliance against the government with other opposition parties, General Ayub’s government had earlier offered him a ministry which he politely declined. He was kept in prison by the Ayub regime until 1964 when he was released due to his deteriorating health.

During the 1971 crisis, he encouraged Abdul Wali Khan, his son and political successor, to work towards a patch-up between Shaikh Mujeeb-ur-Rahman and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Abdul Wali Khan, along with Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, visited East Pakistan. They held lengthy discussions with Shaikh Mujeeb to find out a way out of the impasse. The reconciliatory efforts of the NAP leadership, however, failed and things went out of their control. Had Abdul Ghaffar Khan been anti-state, as is perceived generally, he could have exploited the already tense situation between the two wings.

Later, under his influence, the NAP-JUI government in the (former) NWFP adopted Urdu as the official language of the province. He fervently called for the normalisation of relations with India and Bangladesh after the 1971 crisis. He supported Bhutto for preparing the first draft of the 1973 Constitution. But he was arrested by Bhutto’s government in 1973 in Multan. On his release he lamented: "I had to go to prison many a time in the days of the British. Although we were at loggerheads with them, yet their treatment was to some extent polite. But the treatment which was meted out to me in this Islamic state of ours was such that I would not even like to mention it to you."

He was kept in the dark when Ajmal Khattak started the Pukhtunistan movement in the 1970s. This fact has been authenticated by Ali Khan Mahsud in his book, Da PirRokhanna tar Bacha Khana Pori: Da Pukhtano Milli Mubarizi ta Katana and Juma Khan Sufi in his book, Fareb-i-Natamam. Both are eyewitness accounts in this regard.

It is time to initiate a dialogue to rejuvenate his political ideas to make Pakistan a strong federal state. At a time when Islam is regrettably associated with violence, it is wise to engage with Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s ideals - as a shining example of how, in the right hands, Islam can become a force for positive change.

The writer teaches history at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad