Whether Mugabe’s prolonged rule was a sign of unrelenting dedication or megalomania is for Zimbabweans to determine

It was a less than illustrious ending for a man who once declared that Zimbabwe was his.

The Grand Old Man of Africa passed away in a Singapore hospital aged 95. Far from the state trappings that he had enjoyed for an astounding 37 years. At home, there was talk of a mixed legacy. The younger generation only remembers a brutal dictator whom they accuse of plundering their future.

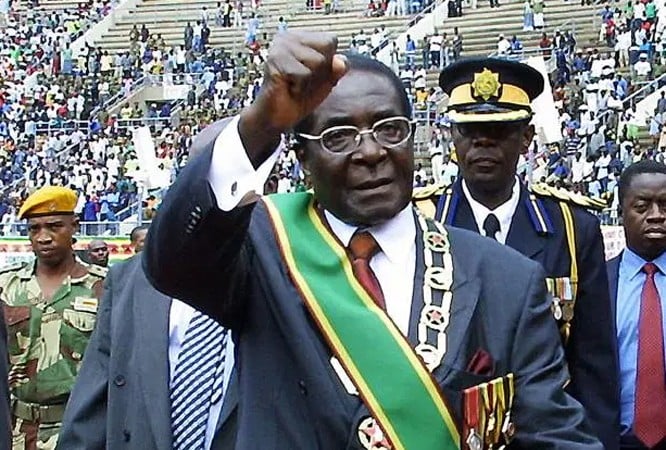

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was Africa’s longest-serving leader as well as the oldest. Whether this was a sign of unrelenting dedication to the country or symptomatic of megalomania is for Zimbabweans to determine. The erstwhile colonial ruler Britain was ill-placed to discredit his legacy.

Mugabe, the son of a carpenter was a committed educationist; having trained and worked as a teacher while earning an undergraduate degree in education. Even his staunchest opponents acknowledge efforts to get as many black children into school as possible. Under Mugabe’s rule, Zimbabwe boasted one of the continent’s highest literacy rates. He was also the man to end white minority rule. In 2000, he passed a constitutional amendment requiring Britain to pay reparations for the land it had seized from the black majority. With added swagger came the ultimatum: failure on this front would provoke compulsory land takeovers.

Yet such gumption was no panacea for the systematic economic degradation and state-sponsored brutality that became synonymous with his regime. It was the increasingly glaring contradictions between the revolutionary fighter at the forefront of the anti-colonial struggle and a strongman seduced by power and riches that ultimately sealed his fate.

Zimbabwe won independence from Britain in 1980; the same year the country held its first-ever general elections. Mugabe was crowned prime minister. But the struggle for economic liberation was just beginning. The puppeteers of the new global economic order -- the IMF and the World Bank -- introduced the notorious Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs) as part of the economic reform package for the developing world throughout the 1980s and 1990s. These were essentially tied to western imports. This period coincided with the world oil crisis that saw the price of crude skyrocket as did the cost of loan repayments. This forced poor nations to borrow even more from these two global lending institutions -- simply to stay afloat. The double-whammy being that these had to be repaid in hard currency.

To his detractors, the Gukurahundi massacres (1983-1987) -- targeting rival political factions -- signalled the beginning of the end of popular support for the Mugabe regime. The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) classified the death toll, which it put at some 20,000, as genocide. Mugabe denounced the allegations as lies. In fact, ordinary Zimbabweans had to wait until 2000 for any show of remorse -- not accountability -- when he simply dismissed the brutality as "a moment of madness".

By 1987, Mugabe was omnipotent; having declared president after doing away with the office of prime minster. What came next was a series of suspect elections. All of which represents a fall from grace for a man who had, at one time, described himself as an intellectual enamoured with Marxism. This held especially true on the economic front. In 2015, after almost four decades in power, the country’s average male life expectancy had fallen from 59 to 58 years. The UN World Food Programme, at this time, estimated that a quarter of the country’s children under five were stunted due to malnutrition; while just over half suffered from anaemia. But it was the question of succession that finally saw Mugabe come undone. The military feared that his wife -- un-affectionately referred to as Gucci Grace -- would take over as leader of all she purveyed. It forced him to step down in November 2017. The armed forces had the backing of the people and the parliament; the latter having initiated impeachment proceedings against the de facto supreme leader of the country.

As the nation prepares to mourn or celebrate Mugabe’s death, important questions will be asked. Can a one-time revolutionary be forgiven for plunging the country into economic dire straits and betraying the very principles of political self-determination for which he had fought so strongly? This is an answer that Zimbabweans alone can deliver.

Mugabe might have come close to realising his vision of celebrating his hundredth birthday while still firmly at the helm. Where he did fall absolutely short was in his steadfast belief that only God could remove him from power. A mixed legacy of a different kind.