A nation state with so much cultural diversity can legitimise itself only through cultural mutuality worked through the process of history

A few weeks ago, I took up the theme of social reform and tried to make sense of its overall impact on the Subcontinent, focusing primarily on the north Indian Muslims. While concluding two-columns long piece, I underlined exclusionary tendencies which are a natural corollary of the puritanism that flows from the reform process.

These exclusionary tendencies were manifest in communal antagonism, sectarian animosity within a community and general atomisation of society from the last quarter of the 19th century. Atomisation in this context means crystallisation of social specificities like caste, kinship and tribal configuration. Atomisation stems horizontal mobility among various social groups.

The British solidified these classificatory social divisions by according them permanence. Thus, watertight social compartmentalisation preceeded with full force and the society got divided into various classes. To this day this remains a permanent feature defining the South Asian urban populace.

The middle class in British India was divided on communal lines. This appeared to be a peculiarity because it is generally believed that the middle class tends to unite or gets divided on the basis of material interests. The situation in India was far too complex. In the late 19th century, religion came here to be viewed rather differently. That probably was the reason that the whole process of social reform centred on a religious ideology and ethos.

The middle classes from most of the religious communities inhabiting north Indian cities saw religious ideology being recast in a reformatory frame as their biggest identity marker. The middle classes in South Asia, therefore, could not transcend the religious/communal differentiation; rather religious adherence developed deeper roots among them.

One may draw yet another interesting conclusion from the formulation: the social regimentation super-imposed by the colonial regime ended up in the formation of class hierarchy along the modernist (Marxist) lines. The situation was ubiquitous, particularly in the urban areas.

We now turn to another point with respect to the reform process among the Muslims of northern India. Let me highlight the fact that the reformers emerging at the cusp of the 19th and the 20th centuries took into their consideration the (socio-cultural) tradition embedded in history, and religion and its reinterpretation (in the theological frame) and modernity drawing on the principles of enlightenment.

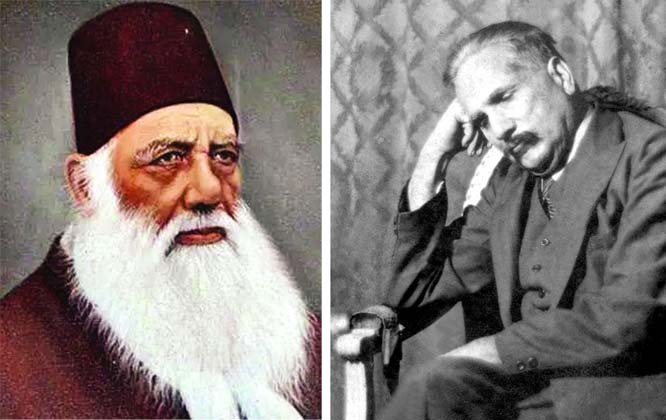

Importantly, a majority of those reformers, including Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Syed Amir Ali, Mawlvi Chiragh Ali, Shibli Naumani and Abdul Majid Daryabadi placed themselves within the Muslim tradition and tried to initiate the change from within that socio-epistemic tradition. Allama Muhammad Iqbal was the most significant synthesiser of three strands of thought. However, his engagement with Pan-Islamism made him difficult to fit in the frame of Muslim nationalism in South Asia. Despite that caveat, he, while conjuring up his conceptual formulation, brought into his focus enlightenment, religious tradition, and history as the principal constituents of his thought (fikr).

I am not including in this analysis the traditions of Deoband, Ahmad Raza Khan’s Barelwi denomination or various Sufi strains, which to my reckoning, were ahistorical in their approach to reforms. Of course, the major flaw in their prognosis is imagining ‘time’ as static and, therefore, denying the evolutionary process in human thought. The consideration that religion is a complete code of life is the general outcome of such line of thinking which, in fact, is part of the problem and not vice versa.

With partition of India and the birth of Pakistan, the three-pronged approach to reform process discontinued. These three lines of thought diverged and were gradually drawn apart to such an extent that they became mutually exclusive. Thus, the possibility of intellectual synthesis leading to an integrated ideological formulation needed for a newly founded state, vanished into thin air.

Theological interpretation became the sole preserve of the Ulema, with the result that sectarianism started gaining strength to such an extent that even state found it difficult to contain. History came to be seen as a superfluous branch of knowledge that did not offer any help in addressing the problems of the ‘present’. The people coming from the secular intellectual tradition reposed their firm belief in the intellectual postulates of enlightenment, thinking Western ethos based on rationality is the only source of redemption.

That divergence has subjected us to intellectual chaos which reflected in our system of education. Our education is ‘functional’ in its very essence and not ‘intellectual’. Consequently, it caters to the need of the ‘individual’, leaving the ‘collective’ to fend for itself. That is one reason we don’t find many thinkers in our midst. Making education amenable to the sustenance of the collective requires that socio-historical context be given adequate importance. Failing that chaos will creep into the very core of our collective.

Striking that balance between the functional needs of the ‘individual’ and the intellectual basis desperately needed for the collective to sustain itself is the biggest challenge for the state and the government. That balance can only be struck if the synthesis that manifested itself in the thoughts of the sages of yore is revived in the context of the 21st century.

Categories like ‘society’ and ‘culture’ need to be invoked vigorously because reform is possible through a debate centering on them. A nation state with so much cultural diversity can only legitimise itself through cultural mutuality worked through the process of history. Sadly, we haven’t made even a beginning to achieve that end. It is high time we did.