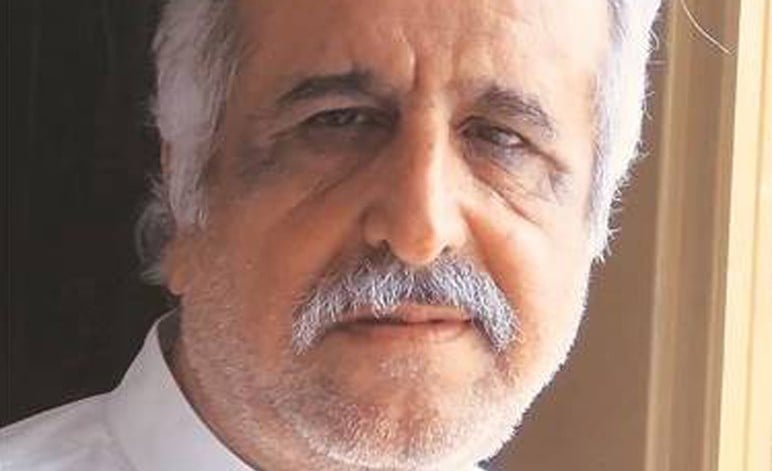

After a thirty-year hiatus, Dr Nasir Baloch has published a collection of short stories that take up themes of socioeconomic injustice and bureaucratic incompetence

Dr Nasir Baloch’s second collection of short stories after a hiatus of some thirty years offers an interesting insight into the author’s preoccupation with social justice, and the development of modern Punjabi short fiction.

The author’s experimental canvas is wider than what I know from my limited reading of contemporary Punjabi writers. There are stories, such as the lead off Ishara band aye, which deal with a person’s worries. A few stories, including ShuhRe and Murday, toy with the absurd and are tinged with mild black humor. The philosophical Kahani turdi rehndi aye seems to expand on the dialogue started by other writers and critics in many languages about the necessity or futility of writing fiction. Almost all the stories appear concerned with foolishness of bureaucracy, society’s failure to afford the poor (mostly men in this book) basic dignity, and socio-economic injustice.

The author seems on firm terrain when depicting characters from amongst the poor and the middle class, but the diction and depiction are both somewhat shakier when dealing with the upper classes. It is important after all to write with empathy about those one is about to report as having a stranglehold on lives of the poor and society’s growth in general.

There is ‘otherising’ of people on both the conscious and the subconscious level. It is important for good writers to watch out for it. Othering in terms of gender is also very easy to slip into. The collection under review is a case in point. When women appear in stories like Shehzadah Saayin, they lack serious negotiation. There is a difference between satire and social critique in fiction and when the two are conflated in less dexterous hands, the result is a caricature which weakens the story, and as the story is weakened around basic structural points, it gravitates towards a less subtle ending.

Shehzadah Saayin, which opens on a strong note about the hard life of a poor boy, descends into a hodgepodge of satire and social critique of the upper classes, who are slaves to fake gadgets associated with modernity but deep down remain stuck in a medieval mindset. From being borderline funny to unconvincing, it ends up on a foolish stroke about the resemblance between a child and the face of the protagonist of the story known as Shehzadah Saayin. Most stories in the collection succumb to this sort of haste or heavy-handedness. Except, perhaps two.

In Ishara band aye, the weaving of inner fear - the fear instilled in a child’s heart taking the form of a red traffic light, invoking the road as a metaphor for life, all works very well. And even when presumably the protagonist has been declared free of the demands of work and social liabilities, the oppressive red light is still there. It is a powerful little story reminiscent of Zubair Ahmed’s Buha khula aye, which I had translated for A Letter from India: contemporary Pakistani Short Stories (Penguin, India). The one story that is a real triumph in terms of and context finding a rare balance is the last in the collection: Kakki da swaar.

Kakki da swaar unfolds patiently and with the right amount of allusions and symbolism. It is the story of Bashku, who is to be found in every middle class household in Pakistan to be held down so the status quo can survive. He is held down with a carrot and a stick, with patriarchal kindness and anger, through guilt and manipulation.

The fact that Bashku of the mirasi lineage has served in the British army is not lost on a perceptive reader. Where it really matters, it doesn’t seem to make much of a difference in elevating his status in the village when pitted against the interest and honor of the zaildars whom he serves and whose Arabian horse he looks after. A woman of the gypsy clan falls in love and elopes with him. Her brothers - à la Mirza Saheban the Punjabi classic literature - have vowed to kill Bashku to avenge their honor.

Riding on a parallel track is the story of the landlords who have entrusted Bashku with their priceless horse. Carried away, Bashku begins riding the horse when out of the owner’s sight. As is expected, he is caught one day. He is angry at being treated less than what he believes he deserves: a little more respect. The two stories converge as the assassins zero in on him and his own sense of remorse at having ridden the animal. He injures himself with the intention to finish off his life and yet the kindness of the zaildars brings him back to life and health. The status quo is saved by saving the servant’s life. Without him, the middle class paradigm won’t survive either.

The story gives a chilling insight into the minds of our intellectuals as they offer no hope of change, the realistic treatment of the subject matter notwithstanding. In contrast, the Korean novelist Yi Munyol’s Our Twisted Hero comes to mind: A young boy moves from Seoul to a small city and thinks that his big city sophistication will help him navigate the tough environment of the school, but to his shock he finds himself at loggerheads with the class monitor, a bully and a cheat, and eventually caves in to the bully; he even begins admiring the bully. But just as the reader accepts the fate of the weak vs the strong, the structure that holds up the bully falls apart.

This requires a certain kind of vision, which is missing from Dr Nasir Baloch’s stories. South Korea, too, has lived through a very brutal military rule which can easily sap intellectual energy, but hope can stand the test and who can see it better than a modern-day fiction writer?

Jhoota Sacha Koi Na

Author: Dr Nasir Baloch

Publisher: Saanjh

Publications Year of Publication: 2017