Words become wood and literature becomes texture: the human and the nonhuman coalesce in Shubhangi Swarup’s Latitudes of Longing

Agha Shahid Ali’s poem, Snow on the Desert, is unfairly remembered only for its crushing nostalgia for Begum Akhtar’s voice, when it also happens to be one of the finest poems about cacti.

The poem begins with Ali driving his sister to the airport. She is leaving Arizona, leaving Ali behind. Despite this central human drama, Ali deftly steers the poem through the abundance of the nonhuman world - snow, sun, earth, desert, plant, mineral - the elements of nature threatening to shift the poem away from him and his sister, who is the immediate occasion of loss for the poet. The poem is slipping away from the human to the nonhuman. And you feel like the poem has definitely slipped out of Ali’s grasp when he ends the first section with the certitude and banality of the word "cactus".

Ali’s genius imbues geography with melancholy. Perhaps only a handful of other poets are capable of pulling this off. In the middle section of the triptych poem, Ali remembers reading about the indigenous Papagos tribe of the Sonora desert who believe that the saguaro cactus is as human as they are. And so, the cactus has memories: "the saguaros have opened themselves, stretched/ out their arms to rays millions of years old,/ in each ray a secret of the planet’s/ origin, the rays hurting each cactus/ into memory, a human memory". The "hurt" of memory is as human as it is nonhuman - the two indistinguishable from each other: "And we are driving by the ocean/ that evaporated here, by its shores,/ the past now happening so quickly that each/ stoplight hurts us into memory".

Ali ends the poem by joining his loss to earth’s loss: "a time to think of everything the earth/ and I had lost". The earth and I. There is no I without the earth, no I that is separate and unaware of earth, of earth’s losses, of its own attachment to the ground and sky. This sensibility - the inseparability of the human and nonhuman - is rare in modern literature, which has largely been cut off from its roots in the deviant and delightful rhythms of the nonhuman world.

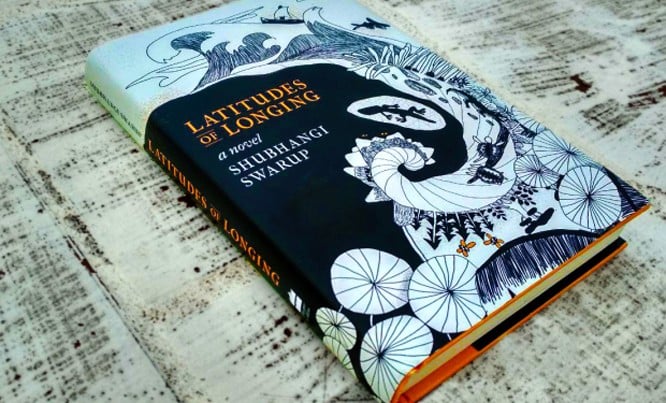

Shubhangi Swarup’s debut novel, Latitudes of Longing, guides us through the affective relations of human and nonhuman characters with the same sensitive genius that Ali shows in his poem. She doesn’t treat the nonhuman world as a prop, but as an equal partner in the dramas of life, capable of evil, whimsy, beauty, kindness, love, irritation - in other words, the whole range of emotions and actions.

The novel is divided into four sections, each representing a geographical feature of South Asia: Islands, Faultline, Valley, and Snow Desert. The first part, Islands, is my unequivocal favourite. It works as a self-contained novella about a couple - an Oxford-educated man and a Sanskrit-scholar woman - who get married and move to the Andaman Islands right after India wins independence from the British.

The scientific, solitary, academic Girija Prasad, "India’s first Commonwealth scholar," has been tasked by Nehru to set up the National Forestry Service. Chanda Devi rivals Girija’s intelligence - "a gold medallist in mathematics and Sanskrit". But, there is much more to her that cannot be revealed by her academic accolades. Chanda Devi communicates with trees and animals and ghosts, she can see a dangerous attack ahead of time, she knows mangoes have theological commitments, and people behave in accordance with astrological positions. Soon, she is a bigger celebrity than her husband on the islands and people come to receive her blessings.

Two very different people are falling in love with each other on a remote island. Swarup sketches the relationship between Girija and Chanda with humour and sensitivity without shying away from the conflicts and tragedies bound to arise between the two. The historical (and geographical; the two cannot be separated in this novel) implications undergird the romantic narrative: Girija’s colonial education is tested by Chanda Devi’s ability to communicate with the nonhuman world - the opening scene of the novel sees Chanda convince Girija to become a vegetarian again because the ghost of the slain goat he had for dinner will not let her sleep at night. The islands themselves constantly reshape the boundaries of Girija’s knowledge, challenging his pre-conceived notions about the nonhuman world and how to study it.

But this novel should not be understood as a simplistic dismissal of science and rationality. Swarup’s writing is a finely balanced alchemical process that combines the languages of science and spirit, history and myth, to create an entirely new (or perhaps, entirely old) language. Consider this sentence: "A larval silence precedes the dawn". Or, the following passage: "The land of mudskippers is where crocodiles meditate. The most ancient of ascetics, they have witnessed evolution play itself out. They have seen gods walking around, enjoying the fruit of their own creation before handing it over." On the level of figurative language - the very essence of literature - Swarup’s writing is unlike most English novelists writing today.

The shift in language goes hand in hand with the cognitive shift of treating the nonhuman world as intimately as the human. Through this simple, yet far-reaching proposal, Swarup transforms the English novel into something completely different from the modern, Western novel, stretching it to encompass languages and knowledges never meant to be carried within its covers.

Towards the end of his life, Girija Prasad stops reading books completely. "He shuffles through them instead, feeling the pulse of a page between his fingers." This is exactly what Swarup accomplishes with her own novel. We simply stop reading it, beginning, instead, to sense the pulse of the pages. In her book, we feel words becoming wood, literature becoming texture, and the novel coming to life.

Latitudes of Longing

Author: Shubhangi Swarup

Publisher: HarperCollins

Year of Publication: 2018

Price: 599INR

Pages: 344