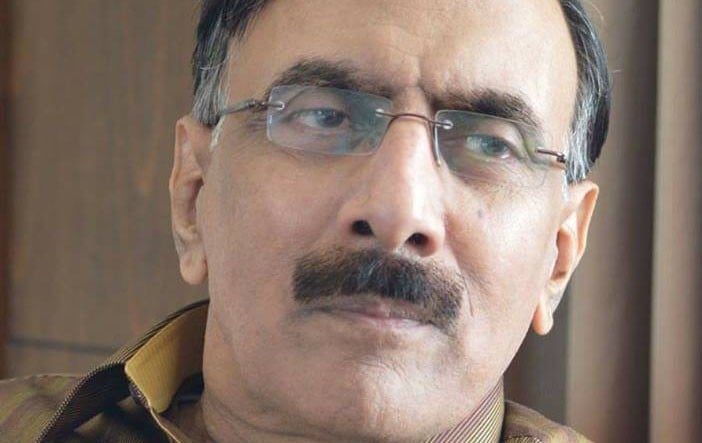

Muhammad Khalid is a poet who sticks to his poetic truth -- at the cost of remaining lesser known

"I can wait, I can think, I can fast." This is how Siddhartha, the eponymous protagonist in Herman Hesse’s novelette replies when he is asked by his female counterpart, Kamla, to show what he possesses to offer against her carnal charms. This trinity of virtues -- waiting, thinking and fasting -- is a prerequisite not only for an ascetic or a recluse, an artist too, is expected to display a certain degree of restraint, patience and self-containment.

But have you ever come across a writer or a poet who is a staunch believer of the significance of poetry in human existence, who has spent a major part of life in a literary hub of the country, who has been publishing in almost every major literary magazine and who is unanimously considered by his readers as one of the most distinguished voices in the contemporary Urdu ghazal, who has already been superannuated as principal of a postgraduate college at Lahore, who always has good publishers at his disposal - and yet, after all his achievements, his maiden collection of poetry is still to be published? Well, I know one such person.

Muhammad Khalid emerged on the horizon of Urdu ghazal in the 1970s, alongside an army of poets, including Irfan Siddiqui and Sarwat Husain. Some of them found instant fame, courtesy the mushaira industry, others took a rather sober start and soon fell victim to experimentation. Both of these types have already been passé and sidelined, if not completely removed by the fresh contenders. But the impact of the trio - Khalid, Siddique and Husain -- mentioned above is felt in the contemporary milieu of Urdu ghazal even today.

A powerful poet with a strong poetic enunciation, Irfan Siddiqui is arguably the only poet that emerged on the post-partition Urdu ghazal scene in India. He was well-received both at critical and popular levels. However, Siddiqui is too deeply entrenched in the classical tradition to produce a salience of his own.

Sarwat Husain too did not deviate from the classical mannerism. Nevertheless, his ghazal offers a remarkable freshness both in its thematic mosaic and in imagery. He now has a cult status among the contemporary poets, not only for his radical methods of coping with love and life but also for his tragic end. In 1996, Husain took his life by throwing himself in front of a passing train in Karachi.

Neither Siddiqui nor Husain pose any challenge of comprehension to their readers - in either their thought pattern or in their mode of expression. But Khalid’s ghazal style is somewhere between that of Siddiqui and Husain’s - a bit more modern than the former but less radical than the latter. It is vague and dense and, therefore, largely inaccessible. Despite the fact that his name is not sufficiently known to the common reader of contemporary Urdu ghazal, he is much revered by both his own generation and the ones that followed - many of them; Ghulam Hussain Sajid, Abrar Ahmad, Akram Mahmood, Afzal Naveed, Aftab Husain and Zia ul Hassan, to name only a few, are clearly influenced by and indebted to his system. Still, the overall aura of Khalid’s ghazal and his sophistication is something hard to imitate.

Khalid is not an advocate of poetry that is devoid of sociocultural responsibilities. On the contrary, he regards poetry as an antidote to the fatal impact of consumerism. He touches on the sociopolitical realities of his age, but these issues are so merged into his poetic aesthetics that he cannot be called a poet of social realism. Khalid is, in fact, more interested in the general human condition from a wider perspective and at a deeper level. He resists diluting the basic flavour of his ghazal in oversimplified statements and naïve realism.

Put in undertones, Khalid’s poetry offers a world - dim in outline - that fascinates you but at the same time, challenges your facile modes of reading. You will find no stock cluster of images - except the recurrent motif of ‘dream’ that is again problematically fluid. Should we look at him as an anti-imagist poet? No. He does create images, but his images are more of sketchy gestalts than fully developed pictures. There remains a lot unsaid; a number of blank points he deliberately leaves to the imagination of his reader.

It is clear that Khalid is a poet not meant for the common public. Even then, his ghazals are eagerly sought after by those with a cultivated taste for refined poetry. But his poetry is not easily available, which is frustrating for his readers.

Some responsibility for this inaccessibility lies with the poet himself for not putting any effort in publishing a collection of his own poetry. As for his disinclination, some of his literary colleagues hold that as he did not publish his book well in time, he fears now that it might not yield the expected results. This perception is based on the viewpoint that genuine poetry has its instant appeal, in other words, a poet’s job is to startle his reader.

Khalid, however, does not seem to subscribe to this definition.

Koi HameN Pahchan Le, YuuN Tau Mushkil Hay

Lekin, Ham Is Bheer MeiN Kho Bhi NaheeN Sakte

[Hard that someone is there that come and recognise usBut surely, we are not to remain unrecognised in this mob.]

In an era when most of our poets are swayed by the allures of media and succumb to the dictates of the market economy, it is heartening to see somebody sticking to his poetic self - even at the cost of remaining less known.

The writer is a Pakistan-born and Austria-based poet in Urdu and English. He teaches South Asian Literature & Culture at

Vienna University.