In South Asia, choosing to write in one language and not the other could be a subtle political statement

Any English writer of South Asian origin, living in a country where the primary language is English, is generally confronted with one question: ‘’But who do you write for?’’ The logic, and perhaps the significance, of such an inquiry, lies more in the location than in the question.

Notice that this question is quite different from another question frequently put to the authors: ‘Why do you write? - something writers often ask themselves as well while trying to figure out their creative processes.

Any such question usually points to the curiosity on part of the inquirer who is eager to know more about the specific writer and thereby her writings.

So, is the question "but who do you write for?" raised in Pakistan and India as well? The answer is both yes and no. Despite the visible multiculturalism in the subcontinent, there is at least one clear-cut difference between South Asia and other first world countries: its predominantly multilingual populace. Most first world countries like the US, the UK and/or Australia etc. are marked by monolingualism where languages of migrants are present only to the point of absence - if they are heard at all, that is.

In South Asia, hundreds of languages and dialects are vying for existence, supremacy, and hegemony, when not every language enjoys the same status, officially or otherwise.

Nobody asks a Bengali writer who they are writing for when they’re writing in the Bengali language while living in New Delhi or in one of the far-off, linguistically homogeneous states of South India. The answer is quite obvious: They write for Bengalis in their native West Bengal or by extension for those who live in Bangladesh or Bengalis elsewhere in the world.

But, South Asian writers who write in English are often asked the question: "But who do you write for?"

The interesting fact is that the works of South Asian writers residing in America are generally categorised as American-South Asian literature. Possibly because of the subject-matter which often concerns South Asian affairs.

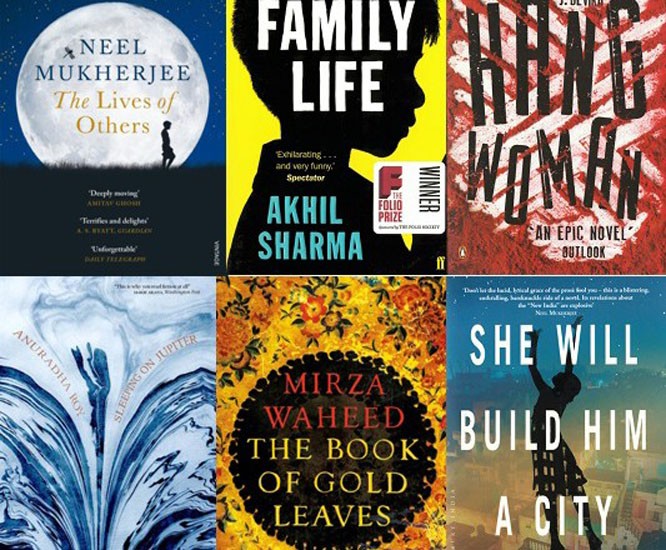

A parallel stream is of those writers living in South Asia but writing in the English language. Whereas the first category is considered promoters of South Asian culture and ethos in the global literary market; those producing English literature locally are viewed sometimes as commercially motivated opportunists with their eyes on the general western reader - those not really aware of the truly South Asian substance and reality.

However, as far as South Asian English literature is concerned, it is mostly the first category that the global literary market considers as a true representative of the region.

Barring the small-scale study programmes of South Asian languages and literature that entertain Urdu, Hindi and other similar languages and to an extent their literatures; it is primarily the literature in English originating from South Asia which is widely received, read, taught, discussed and written about abroad.

Choosing to write in one language and not in the other when the writer is bilingual could be a political statement as is in the case of African novelist Ngũgĩwa Thiong’o who, after having written for a long time in English and having achieved a considerable recognition in this language, decided to quit writing in English to write in his native tongue that is spoken by a comparatively small number of people.

Our Punjabi language activists/enthusiasts in Pakistan who write - apart from their mother tongue - in English and not in Urdu - the language of the dominant discourse and a veritable lingua franca in Pakistan - possibly do so because of their understanding of Urdu as a ‘killer language" for Punjabi in their province.

But, politics could be one of the reasons behind the choice of a language for a creative writer. Allama Iqbal, who was a Punjabi chose to write in Urdu and Persian and never wrote in his mother tongue as he aspired to transmit his message to a wider Muslim audience.

Tagore, on the other hand, remained almost monolingual and stuck to his mother tongue as he was concerned more with his poetic being, his poeticality than nurturing an idea of a poet-prophet.

Creative multilingualism despite being a predominantly South Asian issue is by no means a potential problem.

European countries are overwhelmingly monolingual, whereas African countries have a myriad of mother tongues, but in most cases, they have still not been developed in a more literary manner. The Arab world has a diglossic, even triglossic structure in some countries; dialect and high Arabic, and classical Arabic. But in any case, they all are registers of one and the same language.

South Asia, on the other hand, houses about three dozen full-fledged languages with their considerably rich literary histories. This linguistic plurality is of course not uninformed and has a definitive hierarchy.

Responding to an interviewer, a Lahore-based Pakistani Urdu poet, translator and writer of many books on psychology, philosophy, and history of science, Shahzad Ahmad had once said: "I speak Punjabi, write in Urdu and read English [books]".

Indeed, most South Asians know more languages than one - the educated lot has even more linguistic repertoire at its disposal.

For a South Asian writer, this is tempting and tantalising and at times ticklish too.