Kabul, in cahoots with Delhi, would definitely want to use any movement which may increase troubles for Pakistan

"Your time is up," Director General Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) said about the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM). He also threatened the rights movement that had it not for the reason of COAS advice to deal with the movement gently, taking care of it was not any difficult task. Nevertheless, later during the conference, he clarified that there won’t be any action, which may go against the law of the land.

DG ISPR accused PTM of sponsorship from Afghanistan. There are two different scenarios. First is theoretical. Of course, the incumbent government in Kabul is sympathetic to PTM. Ideally, Kabul, in cahoots with Delhi, would definitely want to use any movement which may increase troubles for Pakistan. Are the two discreetly supporting PTM? Possibly, there cannot be any concrete proof to substantiate the allegation of the duo’s materialistic support to PTM. Even if, for the sake of argument, it is accepted that PTM is in reception of finances from hostile neighbours, how would you prove this?

States’ support to non-state actors in foreign countries is hardly visible. States have honed the skill of seeking ‘plausible deniability.’ The aggrieved state is left without any concrete proof to establish that its opponent state is interfering in the domestic affairs of the former.

The DG specifically mentioned what is meant of lar-o-bar yaw Afghan? [People of] (low and highlands are one Afghan). To the state, this slogan smacks of Pashtun secessionist intentions, envisioning the specter of merging of Pakistani Pashtun (Lar) with their Afghan brethren (Bar) in the so-called Greater Afghanistan. As a matter of fact, Pashtun nationalist narrative has invariably looked upon Durand Line as an imposed colonial boundary that has divided Pashtuns into two states.

In their primordialist and ancient identity, Pashtuns from across the Pak-Afghan border claim same nationhood. Nevertheless, in their modernist and recent identity, Pashtuns of Afghanistan and Pakistan are two different nations. It is much like the division of Punjab in 1947 that divided Punjabis into Pakistani and their Indian counterparts. But that division did not change the primordialist and older identity of the duo as being Punjabis.

Seemingly, Pashtuns from across the Durand Line feel more affinity than Punjabis across the Pakistan-India border. Three facts stand out. First, Punjabis in Pakistan are the most represented people in both the state and society of Pakistan. Punjab quota is the highest in each and every federal or national departments ranging from parliament to security services to civil bureaucracy to economic institutes and forums. Similarly, on the count of agriculture, industries and trade and so on, Punjabis overwhelmingly own more businesses on each of these heads than Pashtuns.

The Punjabi dominance in institutions of state has meant the marginalisation of Pashtuns especially in the peripheral areas of tribal districts or former FATA post 9/11. These were the tribal districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the overall Pashtun populated areas that have mainly borne the brunt of the Pakistani chapter of war on terror both in men and materials. The locus of decision-making hardly involved any Pashtun as policymakers.

Secondly, real or imagined, the perception is no different among Afghans especially Afghan Pashtuns who accuse Pakistan of engineering death and destruction in Afghanistan through Taliban. Thus, these are the common sufferings that bring Pashtuns from across the Pak-Afghan border on the same page which the lar-o-bar slogan demonstrates.

Thirdly, unlike the eastern and western Punjabis, Pashtuns from across the border share the same religion, which translates into strengthening the ethnic or national bond.

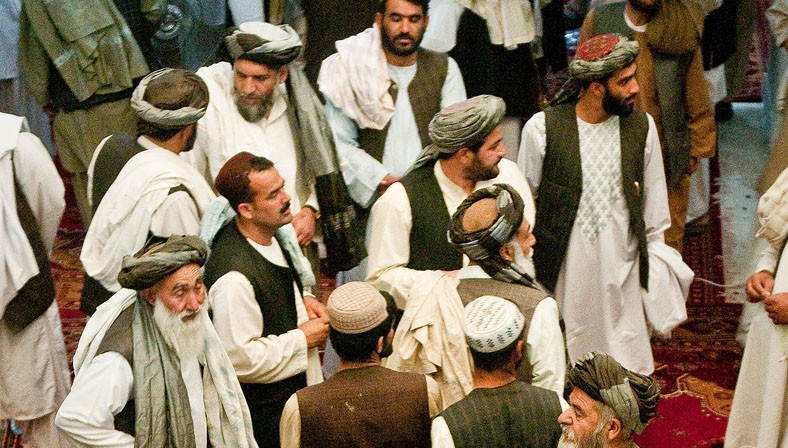

PTM has two main strengths. It has broad based support from almost all segments of Pashtun society. It attracts huge following from Pashtun intelligentsia in and outside Pakistan, women rights activists, political leaders and inter alia political workers from across wide spectrum of political and ideological divides. Likewise, the movement is strictly nonviolent.

In their book why civil resistance works?, Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan analysed 323 violent and nonviolent resistance campaigns between 1900 and 2006. Among 323 there were over 100 major nonviolent campaigns. Their finding was, "nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts". Significantly, relevant in our case is that no nonviolent secession campaigns have succeeded in the data of 323. On the other hand, only four out of forty-one violent secession campaigns have succeeded (less than 10 percent).

The study found out that it is mass participation from diverse sectors of a society which is critical for the success of a nonviolent resistance movement. According to the study, a nonviolent campaign has, on average, over 200,000 members which is 150,000 higher number than the average active members of violent campaign. In their study of the 25 largest nonviolent (20) and violent (5) resistance campaigns, 14 (70 percent) from the former category registered outright success while only two (40 percent) succeeded from the latter category.

No less significant, regime loyalty shifts are crucial to the success of nonviolent campaigns. One common scenario which leads to loyalty shifts is when the regime violently cracks down on a popular nonviolent campaign. In the wake of violent crackdown, still relying on nonviolent strategy increases the probability of nonviolent campaign success by about 22 percent. The study also found, "a nonviolent campaign is 70 percent likelier to receive diplomatic support through sanctions than a violent campaign".

State propaganda has little edge in the face of social media revolution. People have access to counter and alternate narratives. If demands of the PTM are constitutional, legal and legitimate as almost every representative of the state claims so, then what are they waiting for! The easy solution to end PTM is to fulfill their demands. In the long run, state should integrate Pashtun interests both at the state and society levels. Integration of interests is probably the only best option to pacify Pashtuns. Ending interference in Afghanistan can only further strengthen integration at home. Is there any will?