In his latest book, former IGP Tariq Khosa addresses varied issues including state fragility, extremism, civilian supremacy but more importantly an array of police-specific issues

Judging by the column inches devoted to governance issues in our press, especially to police reforms, one could be excused for believing that this country was awash with experts in statecraft, and that the magic solution to all our problems was as close at hand as the opinion pages of the day’s newspaper or the next evening talk show. Alas, there seems little real connection between these endless discussions and write-ups and the problems they are meant to address. The problem is that whereas, on the one hand, the armchair analyst and the pontiff has little idea of the ground realities and complexities of governance, the practitioner, on the other hand, usually really does understand the issues but lacks the articulation, and sometimes the breadth of perspective, to make the right case in the right way before the right quarters.

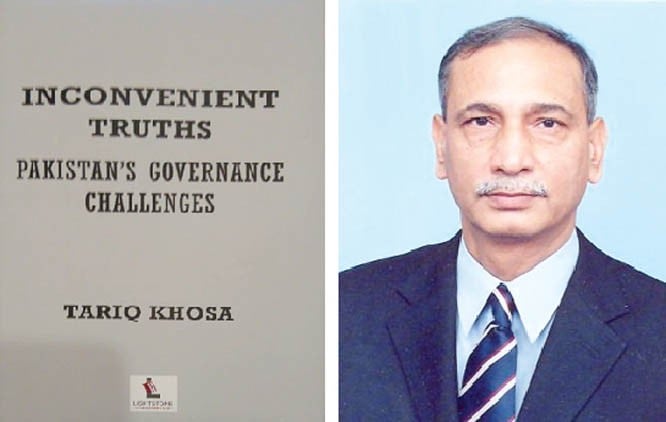

One outstanding exception to this Catch 22 like situation is Tariq Khosa, the highly-respected former Inspector General of Police (IGP) whose Inconvenient Truths: Pakistan’s Governance Challenges has just been published by Lightstone Publishers. The book, which comprises 30 odd pieces Tariq Khosa wrote between 2016 and 2018, picks up from right where his earlier highly acclaimed book The Faltering State left off.

Although, as a society, we are not given to pay much attention to books -- the salacious sleep-and-tell memoirs involving political celebrities being an obvious exception to this otherwise solid rule -- this should be mandatory reading for both our policymakers trying to steer the country out of this latest geo-strategic crisis of our own making as well as for our police and civil servants on the ground.

Tariq Khosa has earned the right to have our undivided attention: he commands an undisputed moral authority borne out of a lifelong reputation as an upright and meticulous professional; he is clear and articulate when putting his message across; and, most important of all, he has the courage to tell it like it is.

Take, for example, our current operation against non-state actors. Among the authors of the "never-implemented" National Action Plan put together in the wake of the APS tragedy in Peshawar in 2014, Tariq Khosa has been calling for such action for years. In a piece titled ‘Plotting Terror’, he writes: "The battle against militancy is yet to be fully fought in the Punjabi heartland where the dance of the wolves should not be allowed. The radical right is ascendant and this theatre of the absurd may haunt our future generations". Elsewhere, he observes: "No non-state actor can survive without internal or external support from security and intelligence agencies".

While unflinching in his demand for the state to delink itself from all non-state actors, without any "good actor"-"bad actor" distinction, he is no proponent of brute force. He writes: "Killing terrorists through staged encounters does not solve the problem; on the contrary, it brutalises society. Terrorists draw their strength from a state that follows their rules of engagement." What clarity in the land of the blind!

Khosa is not one of those civil servants who, having done the bidding of the security-state hawks all their working lives, discover human rights, rule of law and foreign donors, not necessarily in that order, immediately upon retirement. Khosa has practised during his service what he preaches today. The FIA’s remarkable inquiry into aspects of the Mumbai attacks, done under Tariq Khosa’s watch as the Agency’s then Director General, and described in some detail in one of his 2015 articles, is a tour de force investigation into how non-state actors operate.

While Khosa casts his net wide when choosing issues to write upon -- in one piece he narrates how during a meeting he enlightened an Indian officer about the late Eqbal Ahmed’s profound views on possible long-term solutions to the Kashmir imbroglio -- the bulk of his articles are devoted to governance, especially police reforms. Khosa’s police experience ranges from 19th Century-like conditions -- during his undertraining days in Sheikhupura in the 1970s, SP Malik Falak Sher made him do police patrolling on a bicycle -- to 21st-century crime-fighting and counter-terrorism involving high-tech gadgetry and cyberspace.

Any seasoned policy-maker or politician contemplating how to set the country, or for that matter their respective department or ministry, on the right path, could do worse than turn to this book for hard-earned lessons and wisdom. State fragility, extremism, civilian supremacy, financially-clean leadership, freedom of expression, and an array of police-specific issues including its depoliticisation, a new model for urban policing and the extension of policing to previously loosely governed areas are among the many and varied topics Tariq Khosa addresses, in one form or another, in his book.

Similarly, young civil servants and police officers, who may be growing weary and even cynical as they navigate daily the snares and pitfalls of our socio-administrative landscape, would find in the author of this book a man who has tread an equally arduous journey and come through with honour, grace and a moral compass still pointing to the Truth.

Ultimately, according to Tariq Khosa, it’s all about the truth - not just mouthing hollow allegiance to it, but also facing it, no matter how inconvenient the endeavour. The Truth shall, at last, set us free.

The author can be reached at thereluctantcolumnist@gmail.com.