‘What went wrong with Jamaat-e-Islami? [henceforth as Jamaat or JI]’. This query by a few young scholars nudged me to contemplate about its role in Pakistan’s politics which to my contention has been seminal. Besides, Jamaat is the only right-wing organisation in the country with a profound intellectual profile.

Its influence among the urban middle classes in the 1960s and ’70s was immense. Along with Majlis-e-Ahrar that formulated Khatam-i-Nabuwwat as a concept (that has virtually become the centre-piece of Pakistan’s ideology), JI wielded optimal influence on the literate sections of the society.

Even Jamaat’s staunchest opponents saw it as the most well-organised party in the entire country. More importantly, JI remained an ideological vanguard of the right-wing parties in their bid to stem the soaring influence of the left. The right-wing counter-narrative to the socio-political assertions of the left-liberal ideology came mostly from the Jamaat. With the left having run out of steam and become marginalised, Jamaat’s own relevance became questionable. With the dissolution of the ‘Other’, in the wake of Soviet Union’s demise, Jamaat’s ‘Self’ could not hold its own and its erosion set in.

In a political scenario overwhelmingly dominated by right-wing parties, with their liberal-left adversary consigned to insignificance, the elan vital (borrowing the phrase from Henri Bergson) in Jamaat is flickering unsteadily. That may be one answer to the query.

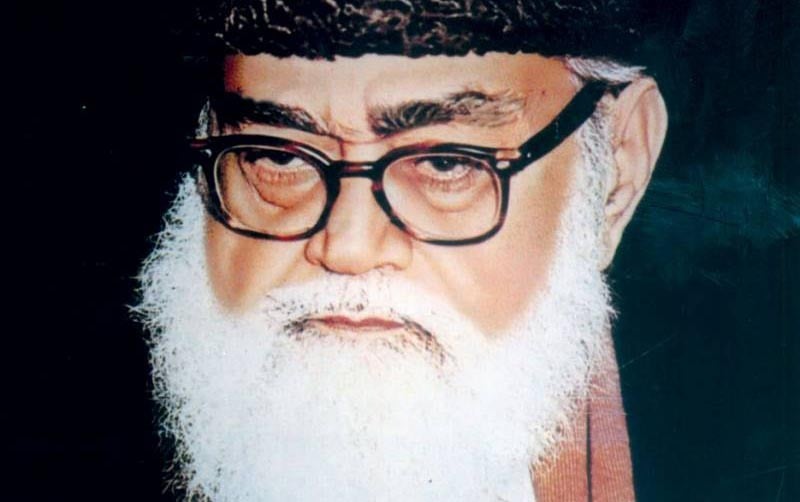

Jamaat’s founder Maulana Abu Ala Maududi (1903-1979) had arguably been the most influential scholar of Islam in the entire subcontinent since partition. Even forty years after his passing away, Maududi’s charisma and legacy continue to have indelible imprints on Jamaat’s rank and file, largely through his publications. His intellectual influence resonates internationally ever since the debate of political Islam and Islamism has pervaded academic circles.

More so, Maududi was flanked by a string of scholarly figures like Amin Ehsan Islahi, Khurram Murad and Prof. Khurshid Ahmad but obviously none of them could match the caliber of the former (Islahi parted ways with the Jamaat but he was well-respected by its members.) The ability to synthesise and re-interpret Islamic thought in the light of modern intellectual trends and articulating it in a lucid manner distinguished Maududi from the rest. Bringing into use the rational explanation of Islam and also according it a systemic/well-organised structure made his version of Islam time-bound and therefore ephemeral.

Thus, Maududi’s thought could hardly be subjected to re-interpretation to make its impact longer lasting. That is the usual dilemma with the thought that is well-organised, rational and clearly stated. Iqbal remains relevant partly because his thought is expressed through poetic diction; even Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam is a multi-layered text and therefore remains amenable to newer interpretations in a changed circumstance.

Reverting to JI, I will argue that it needs a fresh ideological framework which can enable it to be relevant in the current situation. I have already stated in one of my previous columns that the parties and organisations that remain tied to the ideology of its founder cannot last long, and obviously Jamaat is no exception.

The role of Islami Jamiat-e Talaba, (IJT) the student organisation of JI, is very crucial in the fundamental change that is in evidence in recent years. After the tenure of Mian Tufail Muhammad (1914-2009) as its Amir, Jamaat leadership which held its reins came from the IJT.

Sadly, the first generation of Jamaat failed to inculcate the values it held very dear among its posterity. Intellectual profundity, cultural sobriety and scholarly disposition gave way to activism which was mostly expressed through violence and vandalism. Ideological content was substituted with gimmickry, sloganeering and social vigilantism. Ziaul Haq used the Jamaat for the perpetuation of his own rule, and for that purpose Afghan jihad was played out in the most effective manner to rope in the Jamaat zealots. Afghan jihad also played its part in infusing militancy among the IJT youth in the 1980s. I consider the year 1974 very significant in the changed characterisation of the Jamaat. That year is mostly known for excluding Ahmadis from the fold of Islam, and it was the same year when the religious right in Pakistan attained a sense of impregnability. It managed to bring Z.A. Bhutto’s popular government to its knees.

Bhutto’s vulnerability became quite evident when discontentment started brewing up within the ranks of Pakistan People’s Party itself. Bhutto in those circumstances had no option but to join the chorus. For the Jamaat, that year was important because IJT stole the limelight throughout the country for the first time through its confrontation with Ahmadis at Rabwah. IJT students from Nishtar Medical College, Multan were roughed up by the Ahmadis in the wake of some altercation. Why and how did the scuffle began that conflagrated into full scale violence is still shrouded in mystery. But that confrontation, which was widely covered by the media and hailed by all religious parties, subsequently, triggered a political movement, and worked as eureka for IJT.

That moment was seized and capitalised on by the student wing. Thus, the process began which eventually catapulted IJT to the forefront of the Jamaat. Confrontation instead of contemplation became their central ploy for self-assertion. College and university campuses became the site for their political action, which brooked no opposition or difference of opinion. The politics of agitation became the marked feature of the Jamaat, primarily because it had been operating in a state of intellectual vacuity. Their actions were not underpinned by any intellectual current; therefore it could not justify them through argument. Thus, coercion and confrontation were the means which were employed with impunity.

In view of that, people got alienated and the Jamaat had to feel contented with its laurels of the past. For the last forty years, the socio-political situation in Pakistan has been rife with sectarianism which further squeezes the support base of such parties like Jamaat-e-Islami.