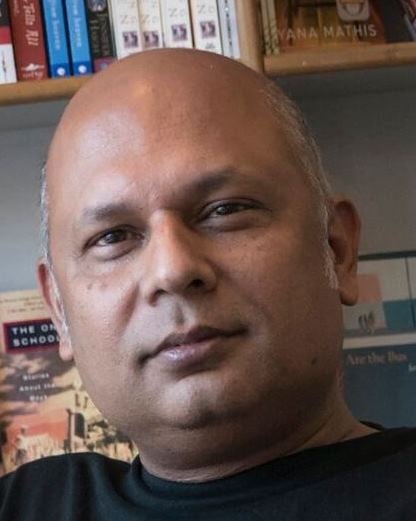

Interview of Harris Khalique, poet, writer, secretary general HRCP

The News on Sunday: Being a poet, columnist, teacher and human rights defender, how do you look at the level of intolerance in our campuses in the backdrop of the Bahawalpur incident? Is anyone thinking about the students’ thought process, what are we educating them in the form of text books?

Harris Khalique: The faculty and student bodies in our colleges and universities reflect as many streams of opinion or a lack of any opinion on different matters as is the case with the larger environment outside these campuses. We are not simply a predominantly religious country. There are some other countries which fall in that category. We have turned into a bigoted country where inherent fear has replaced free will in all matters, including faith and political opinion. The powers that be have let the conservative clerics, proselytisers, thought leaders and televangelists fan bigotry and intolerance. Perhaps the majority still does not subscribe to extremist actions but they are powerless and held hostage by those who have long been allowed to exercise the agency of violence. As far as curriculum in schools is concerned, it is not the only thing that needs to be revisited. What I have found most problematic is what the teacher tells her or his students in the class which may even not have been written in the textbooks. Then there are meta-messages students and young people receive both through the pulpit and the media. The thought process of such students and youth cannot be altered in isolation.

TNS: This perhaps is the first incident of its kind. But we haven’t seen a strong reaction from the state, or even the government. How important is/was that reaction?

HK: The absence of an appropriate reaction from the state or government confirm that even the most powerful fear for their security and losing their conservative vote bank if they speak on such matters. I have said that before and will say that again that the assassination of Salmaan Taseer was a watershed event in this respect. The elite rulers or those heading state institutions find it hard to trust their own staff and security detail any more for they largely come from the class which was radicalised by these elites themselves to serve their political aims.

TNS: The society, too, seems to have opted to remain silent. There is no response from fellow teachers or debate and discussion on this incident. Where will this lead us?

HK: To an extent yes but I am not sure if that is entirely correct. Some of the slain professor’s own students came forward and wrote in his favour. There were vigils in other cities organised by students, teachers and members of civil society. But there is an atmosphere of fear and intimidation. People also watch how their political leadership responds to these events and situations.

TNS: In an environment of fear and intimidation, can teachers teach or say what they want to? As a teacher do you see a distinction between public and private institutions with regards to freedom of speech?

HK: Absolutely not. Teachers who are even religious in their personal lives but want to push the boundaries for rational debate, question preset notions and primordial norms, and, encourage critical thinking choose a difficult path to tread. There is some difference between public and private institutions. Public institutions harbour more conservatism but even within private institutions certain lines must not be crossed. Academic freedom and a spirit of inquiry are challenged like never before in Pakistan. This will lead us to further ignorance and bigotry, more violence and retrogression, and an angry, unhealthy and fragmented society.

TNS: It seems that students are being educated from various sources now, more importantly social media where religious extremism is being freely propagated while the more tolerant or progressive view isn’t allowed. How do we teach the value of freedom of expression and at what stage?

HK: This has become a global problem and not just limited to Pakistan. There is a rise in narrow nationalism, racism, misogyny, religious hatred and communal prejudice. What is unique about Pakistan is the dearth of imagination among the decision makers in dealing with this problem, if they see it as a problem. Freedoms and rights are inalienable and indivisible. We have a colonial way of dealing with dissent. Societies and nations do not progress in an atmosphere of fear and intimidation, coercion and violence.

TNS: What about the laws on our statute books? Do they promote intolerance in society?

HK: Ironically, in the last twenty years or so our society has become more radicalised than the state wished it to be. Laws are continuously needed to be made pro-people and humane but there is a shrinking constituency for progressive legislation. I give you an example of some pro-women legislation in our parliament and provincial assemblies and the desire among many legislators and policy-makers to introduce more such laws. Rather than welcoming these laws and policies, there are influential groups in society who have strong objections to the realisation of the rights of women and make it impossible for these laws to be properly enacted and implemented. Consequently, little possibility remains at the moment to even question the misuse of laws on blood money, blasphemy, evidence, etc., introduced by General Ziaul Haq in the name of religion, leave alone altering them even in the light of enlightened Islamic discourses.

Also read: "Our students are a reflection of what we have taught them"

TNS: What in your view should be the solution to improve this regressive thinking in our academic institutions so that they start producing both critical and tolerant minds?

HK: First and foremost, the permanent institutions of state have to commit themselves to changing the course. Press freedom is linked to democratic freedom which is linked to academic freedom. Citizens must not be seen as subjects and students as cannon fodder for pursuing political or religious aims. Besides, there is an absence of dialogue between different schools of thought, including those religious scholars who take a wider view of history and politics. A healthy society is an inclusive and plural society where a thousand flowers bloom.