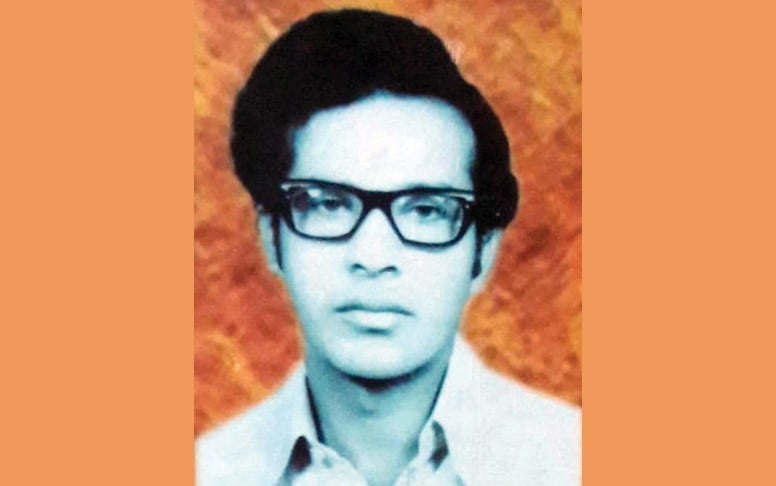

The life and tragic death of the legendary Urdu poet, Sarwat Husain

When I first met Sarwat Husain, somewhere in the distant past, the memory now nearly minuscule, as if I was looking through the wrong end of a telescope, he exuded joy. There was buoyancy in his body language, his frank smile and lively chatter. How could I guess that behind the cheerful exterior was a mind, haunted and undermined by some bleak sorrow or trauma which was hard to put your finger on and drove him to what looks like suicide.

The pettiness of ordinary life often defeats us. Even poets, gifted though they might be, are not immune from the tyranny of the commonplace. But unlike most of us, the poets manage to hoodwink the overwhelming shabbiness and discover chinks through which the world looks like an altogether different place, sometimes ablaze with sadness and misery, and on other occasions, awash with a sensation of togetherness and communion.

It is what we come cross in Sarwat’s poetry, dignity in defeat and estrangement and the sense of a world completely vivid and incomprehensible in its loveliness. There is a charming song, magically sung by Louis Armstrong, beginning with these words: ‘What a beautiful world’. Sarwat could say something similar but with the realisation, which is a true poet’s prerogative, that there is still a residue of wonder, an urge to live on, within a surfeit of miseries. His rapport with the small joys and sorrows of the common men and women, who live uncared for, as if invisible to those who lord it over them, is remarkable. It touches us because it is emphatically sincere.

One of his nazms begins with the line: "A poem can begin anywhere." Strangely enough, a poem by Kathleen Raine in Temenos-2, a magazine she published herself, has a similar first line also: "A poem can begin anywhere." It is unlikely that Sarwat might have read her poem. Even more improbable that Raine might have read Sarwat. She did not know Urdu. In any case, the similarity comes to an end with the first line. The poems immediately veer off in totally different directions. Although a very good poet Raine has been generally ignored by a lot of modern poet and critics who dislike the mystical elements which dominate her work. The matter, however, need not concern us anymore. I brought it up only to reinforce the fact that an invisible net of sensibility can bring poetic imagination across the world in synch.

In any case, Sarwat is not a mystic. He is a lover and a wanderer. He feels that the world, with its natural but impersonal grandeur, belongs to him and he must roam in it, lost and found again and again, peering into every nook and cranny, to winkle out new solitudes and convivialities, to point out hidden sources of rapture. Even the ordinariness of a scene is transformed into a glow, with a pictorial sensibility, live as a watercolour. Read this nazm entitled "Here in the suburbs," to savour his unruffled mastery.

"Here in the suburbs,/ right at the moment,/ when the earthly clocks are striking half past seven,/ a wheel is being made./ It is no easy job to bend blocks of wood into a curvature,/ light spreading out from its own centre./ It is the first sight after a woman’s naked body/ which has made me stop/ and I no long remember/ that the planet also has its weather/ and I also have a name./ A pair of wheels leaning against the door./ The carter will come and take them away./ The carter will come and take these two flowers away."

It is interesting to note how much this apparently simple nazm reveals and how much is left unsaid but can be found lingering in between the lines. It is early in the morning, outside the metropolis somewhere, or to put it in another way, far from the madding crowd. You hear the clocks announce the time in unison, like a chorus. All is right with the world. Then you observe another ordinary thing. A wheel is being made for a cart. A simple task, but requiring hard work, done by hands by an ordinary person, becomes a mythical undertaking. The spokes radiating from the hub are like rays issuing from a centre. The artisan seems a sunmaker. The wheel epitomises the sun. The sight is so striking that the onlooker finds himself unable to move or look away. He has hitherto found only the nakedness of a woman the most spellbinding thing in his life. A reaction common enough. But not everyone will find the experience of seeing a wheel being crafted so absorbing. There is a sudden change in the level of consciousness. The poet is all at once lost to the world, no longer aware of his identity. After a brief trance-like moment consciousness returns. He realises that nothing beautiful or well-made will last. The carter, death’s angel in the context, will call and take these handsomely crafted things away. The wheels will keep on turning over across rough roads, through mire and rain, summer and winter, heading towards a final breakdown. All that is lovely to behold, in human beings or artifacts or breathtaking scenes, appears in a flash, like an epiphany, only to disappear forever. A poet or writer alone can put us in touch with an afterglow.

Some of Sarwat’s ghazals are excellent indeed but his forte is best expressed in nazms. He has written prose poems with a fine sense of how they should be devised and delimited and invariably finds a diction appropriate for them.

There is a residual of romantic effervescence in his work which, however, does not give way to limp self-pity or hazy nostalgia. On the contrary, it has to be acknowledged that he can with vigour and a cutting edge condemn the acts of injustice and barbarity which mar the world around him. One has only to read his nazm "The Death of a Human Being," written about the disastrous events of 1971, to see how he can, without resorting to rhetorical flourishes, express his anger and grief. He is primarily a poet of judicious intensities, not of overt insolence.

Only two Urdu poets have written perceptively on Sarwat’s poetry. Suhail Ahmad’s introduction to Sarwat’s first collection of verse, is a brief but incisive look at the issues and images integral to Sarwat’s visionary depiction of his real or imagined surroundings. Ajmal Niazi, on the other hand, has reviewed Sarwat’s achievement with great passion and lucidity. It is a pity that someone, so gifted as Sarwat was, should have taken his life.

(Poetry translation is by the author, Sarwat Husain’s Kullyat has been published by Aaj, Karachi)