In this book on Sindhi literature, Attiya Dawood provides an overview of a literary expression that has spanned over many centuries

The book by Attiya Dawood is very useful to those wanting to get acquainted with Sindhi literature because it provides an overview of a literary expression that has spanned over many centuries. Without going into detail and a microscopic analysis of what happened, we are told that the first reference to Sindhi literature was in an eighth-century book called Kolbiya Malakatha by Acharya Adyotan Soori.

Then in the eleventh century, there is evidence of the verses of Samang Charan. Since it consisted of high lyricism, geet and dohe, these were also probably sung because in the Soomra period, bhat and charan, the roving minstrels, sang these lyrics as they took the rounds of human settlements.

In the Soomra reign, geets and lyrics regarding war were more popular. At about that time these were expressed in the various lok dastaans (folk tales) like Sassi Panoo, Dodo Chanesar, Morzo Mangermuch, Sorath Rai Diyaz, Monal Raano, Umar Marvi, Lelaan Chanesar and Sohni Mahiwal.

After the advent of Samma rule, the same trend of expressing the sensibility through tales continued but more were added like Noori Jam Tamachi, Jam Lakho, Mehar Rai, Jam Adho Hotal Pari. These became popular because probably they married love and romance with resistance and rebellion.

In the second phase of Soomra period, the famous poets were Pir Satgur Noor, Peer Shamsuddin and Peer Sadruddin as they expressed themselves through ginan (religious poetry sung ritualistically) but these also reflected the ethos of the time. In other works, Samang Charan and Bhagon Baan wrote poetry in the folk tradition and it has many formal variations to it. At about the same time the name Markhan Sheikan is mentioned and she was the first woman poet or probably the one whose name survived the ravages of time.

According to the author, since the earliest of times, Sindhi literature has been very much involved in the societal problems. Even in the earliest of literature, there has been some evidence of acute social consciousness which became the primary motivation for creative activity.

Like other parts of the subcontinent, Sindh too was exposed to foreign invasions but most of these invaders then settled down and became part of the evolving mosaic of Sindhi culture. This soaking up quality is one of the major characteristics of Sindhi culture. Because of this quality, even as poets and writers wrote about the invasions and the divisions in society, their individual voice of liberation or protest was fully imbued in the local idiom.

Similarly, during the colonial era, Sindhi literature did not shut itself up in its own past and glory but opened itself to other forms that were being introduced through this colonial encounter. But at the same time, the resistance theme in that period gathered intensity and allied itself to the desire to be independent in action and thought.

With independence and migration, the Sindhi literature took off differently. In India, it was heavily laced with nostalgia and a sense of having lost the place of one’s own origin, while in Pakistan the new reality of the massive migration shook Sindhi society completely. This coexistence or grudging coexistence became the theme of that period. It was further strengthened with the establishment of one unit, as the Sindhis felt that their identity was not only threatened but being erased.

In Sindhi two types of literature have prevailed - one that protested loudly about the occupations and the injustices and this probably falls more in the realm of propaganda, and then there was a deeper and a more recollected reaction that has left a deeper imprint, Politics has in many ways deeply affected the Sindhi sensibility but it has been nurtured in the cradle of an evolving culture. Themes have been given due importance in literary output and, for this purpose, one can say that the complexion of the literary tone has been of resistance.

But according to Attiya Dawood, Sindhi literature has been in a state of decline for some time. She also lists the various reasons why she thinks it is so; firstly, Sindhi Adabi Sangat since 1953 had been performing a positive role as it provided a safe refuge for the writers. Since it was created by those who were enlightened, it also promoted literature that nourished these values. A weekly meeting was held on a regular basis and the writers and poets presented their latest works followed by a heated discussion. This also prepared the writers to be more open-minded and created an environment for an acceptance of criticism.

Headquartered in Karachi where it stayed very active for a very long time, it gradually started to fade away. There were many branches of this Sangat in the various cities of the province, run by writers who were known for their creative output and were respected for it. But the spirit of enlightenment that it nourished was challenged and, from there, its standard started to show a downward curve.

For the creative writings to maintain a certain standard, it is absolutely essential that the standard of critical writings remains high as well. The creative act and the critical act work hand in hand and then both are mutually exclusive so to say. The publishing houses, too, did not really care about the quality of the writings. The number of publications increased but the stringent standards that were enforced started to slacken. It also resulted in many of the writers starting to publish on their own. It was followed by a lack of professionalism and many works being advanced for reasons of pure sentimentalism rather than merit.

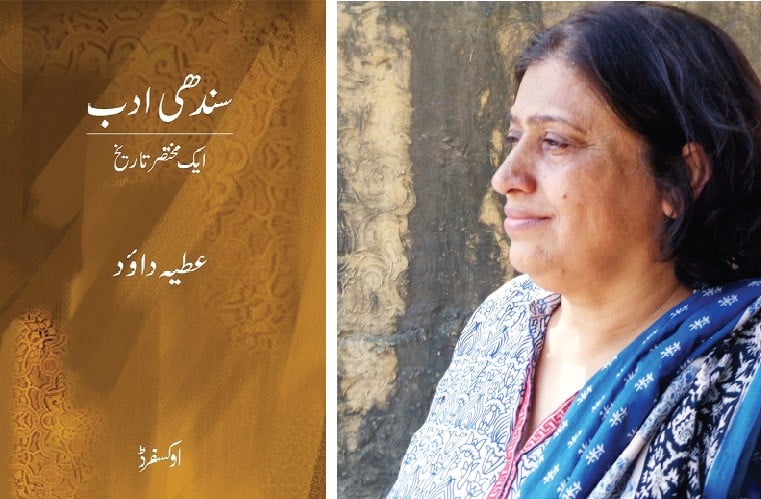

Sindhi Adab – Aik Mukhtasar Tareekh

Author: Attiya Dawood

Publisher: Oxford, 2019

Pages: 273

Price: Rs625