Winston Churchill’s quote "the best way to make history is to write it," which I read for the first time in Richard Nixon’s book, kept me enraptured and gave me immense satisfaction. The inference that one can draw from this is that a historian makes history just by writing it. Of course, as a historian, writing history is my vocation, therefore, I too fall in the category of makers of history. In a milieu where history and historians are both relegated to academic as well as social neglect, such quotes are indeed a veritable source of solace and consolation.

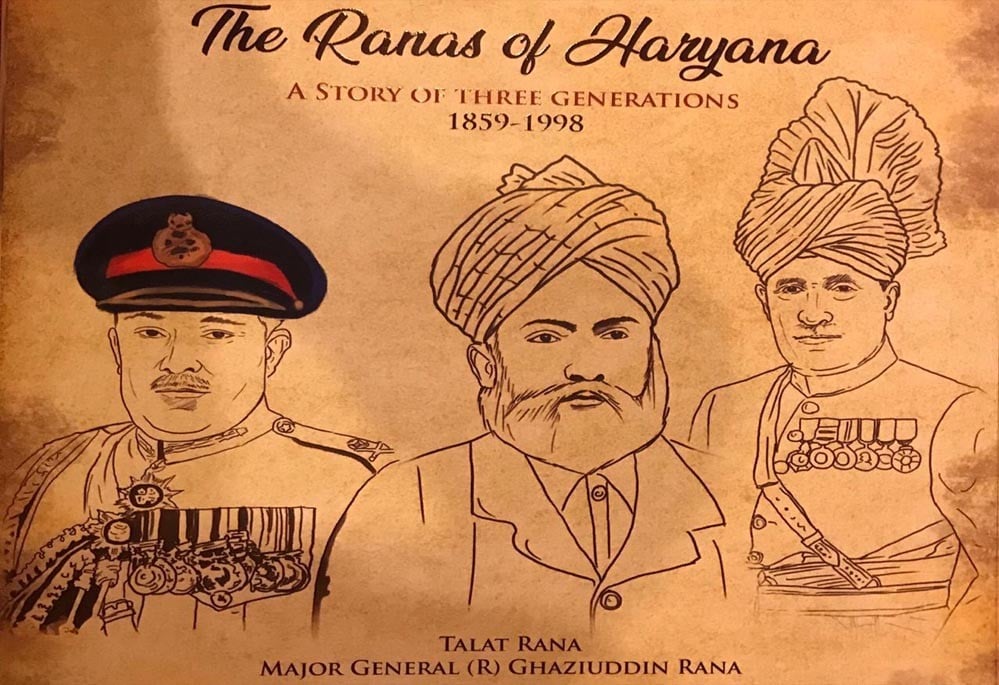

My pleasure and satisfaction is immense because the number of such makers of history stands swelled today by two. Mrs. Talat Rana and Gen. Ghaziuddin Rana have joined the ranks of historians, which must be a great source of gratification for the fraternity of historians. One must not forget that history is kind only to those people who write it themselves. We must not lose sight of the fact that the greater the number of historians, the more narratives of history there will be, which obviously will ensure a safer future for us and for our posterity. Multiple narratives mean there will be no one grand or meta narrative, which is what our era needs to understand.

Before I introduce this book, let me shed some light on why such narratives, generally designated as socio-cultural histories, hold a lot of importance. The very practice of history-writing in Pakistan has been confined to the mere arrangement of certain facts in a sequence, and those facts are inevitably political. Consequently, most of the narratives of history churned out in Pakistan are bare political commentaries without even a fleeting allusion to cultural or social traditions and conventions. Description of political events without their social and cultural moorings is only historical meta-narrative construction.

Viewed in that context, the book under review has a tremendous academic significance. Its salience increases because we do not find any credible account on the Rajputs despite them being one of the three most important clans currently inhabiting Punjab. The book Ranas of Hariana is a breath of fresh air primarily because the ‘history’ books produced in Pakistani academic circles are mostly ‘national’ not only in their characterisation but more significantly in their epistemic focus.

Family histories and autobiographical accounts add a fresh dimension to that monotonous trend that dominates history teaching in universities and colleges. Therefore, the authors must be commended for joining the ranks of those who want the frontiers of the discipline of history to be expanded.

The ancestral origins of the Rajput clan are somewhat confounded because the point of their origin exists at the very confluence of history and mythology. I am asserting that because Ram Chanderji’s status as the first ever Rajput in our world is shrouded in mystery; it is debatable whether he was a historical figure or a figment of mythological imagination. Ironically, this is a universal conundrum that makes the question regarding the origins of castes, communities or kinship rather insoluble.

Leaving these tangled cobwebs of ascertaining the exact origins of the Rajputs aside, what is fascinating is the Rajput tradition, which can be summarised as the epitome of four ideas: romance, valour, uprightness and pride. All such adages like sar kat sakta hai magar jhuk nahi sakta (a Rajput’s will choose beheading over bowing to anyone), or such high-sounding words and phrases like Aan (sense of self), Sanskriti (culture), Parampra (tradition), we owe to the articulation of Rajput tradition. However, equally fascinating, and seemingly opposite, aspect of Rajput tradition is it’s not being rigid, allowing it flexibility to adapt to changing times.

If Rana Sangram Singh of Chittorgarh in the state of Mewar was a diehard follower of the Rajput parampra, a representative from his succeeding generation, Rana Hari Singh embraced Islam, thereby effecting a synthesis between the centuries-old Rajput traditions and Islam which accorded the Rajput ethos, an added measure of impregnability.

Coming from Rajasthan and taking up their abode in Hariana (district Hoshiarpur) during the reign of Mughal King Shah Jahan amply demonstrates that flexibility which is an essential ingredient for survival against all odds, no matter how onerous they may be. In Ranas of Hariana, one of our protagonists, Rana Jalalud Din Khan (1859-1926) acquired English education when the Muslim elite were still ambivalent about it. Even while Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was struggling to convince the Muslim Ashraaf to equip their children with modern education, Rana Jalalud Din Khan went to school, acquired English education and went on to join the police service under the British, a very wise step under the circumstances.

When posted to a difficult region like the North West Frontier Province, he never shirked and discharged his duty with a consciousness typical of a daring (Rana) Rajput, who knew only to surmount every challenge coming his way and never to be succumbed by it. Learning in the process the language and other social subtleties that people’s lives were punctuated with, seems quite an impossible feat in such trying circumstances but Rana Jalalud Din performed it with grace and diligence. All these details have been furnished in the book at some length, while maintaining the Rajput aura of romance and adventure.

The Rana clan kept climbing the social ladder with the onward march of history under Khan Bahadur Rana Talhey Mohammad (1884-1956) who seems to have wielded tremendous influence on his clan and kin. A graduate of F.C. College, suave and civilized in his bearing, exuding the charm and charisma of a born leader, Rana Talhey was extremely gregarious and personable, with an uncanny ability to forge friendships. Like his father he too joined the police force and spent all his active service in the NWFP. Later, he was seconded to Patiala state as the Inspector General of Police, where his friend Bhupinder Singh was the ruler. Music connoisseur, tennis player of extraordinary merit, possessor of incredible sartorial taste and sense of style, he was so well-rounded a person, that an example of such a person is hard to find now. Rana Talhey Mohammad was an incarnation of the perception, widely circulated far and wide, which said: The duality in the Rajput character was astonishing. He was a grim warrior, forever ready to draw his sword, taking the cruelty, horror and pain of war in his stride. He was gentle, warm in his hospitality, a lover of music and dance, and kind to the womenfolk, even those of his enemy.

The last protagonist in the narrative is the larger than life figure of General Bakhtiar Rana (1908-1998). Like his father Rana Talhey Mohammad and grandfather, Bakhtiar Rana retained primal status in the Rana clan. Any word uttered by him was respected and complied without demur not just by his family but also by the extended clan as well as others around him. Like his father, he studied at F.C. College Lahore. Bakhitar Rana then joined the Indian Army and fought in the Second World War. After partition he was among the senior-most army officers who chose to migrate to Pakistan. He rose to the rank of a three-star general, making his position virtually unassailable in terms of worldly achievements. Keen golfer and tennis player, Bakhtiar Rana had profound interest in sports that might be a reason for his accepting the responsibility of heading the Gymnkhana Club in Lahore.

All said and done, Bhakhtiar Rana was a complete man, devoted to his family and kinsmen, a thorough professional and the upholderof Rajput aan, parampra and sanskriti. As he was proud of his Rajput origin, Rajputs must also be proud of having such a scion.

This book, Ranas of Hariana is the outcome of love’s labour that the representatives of the fourth generation of this family have assembled for the benefit of the fifth and the sixth generations. There is no greater feat than this benefaction of the elders for their posterity. Now it is up to the youth to be acquainted with their past because without proper grounding in the past, the future become elusive and uncertain, and the present remains what it is now: bleak and uninspiring.

(This column is a speech delivered by the author on the launch of the book Ranas of Hariana)