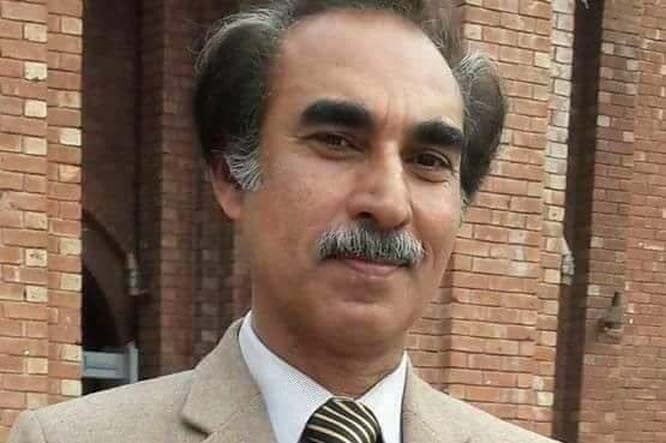

History of various castes and families in Punjab and how it has been allied to the land and the place is well-documented in the works of Asad Saleem Sheikh

Asad Saleem Sheikh has been writing about Punjab quite prolifically over the last many years. Many scholars and those in love with the land have written about Punjab and its changing phases, geographical frontiers and linguistic patterns. Noor Mohammed Chishti can be considered the father of modern history cum chronicle writing in Punjab, and since then many have come forward and added to the growing body of writings on Punjab and the various towns, villages and cities of the province.

Makhzan-e-Punjab too was one such laudable attempt by Mufti Ghulam Sarwar Qureshi Lahori as he combed the entire countryside and wrote about the various towns, villages and the hamlets in his broad sweep of history and the people that inhabit the land.

One of the more significant works of Asad Saleem Sheikh has been the encyclopaedic Nagar Nagar Punjab, comprising the various towns and villages of the province. The usual focus has been on larger settlements in the shape of cities as they existed in history or as they exist now, but not a lot has been written extensively on various towns and villages and other human habitation. They may not be that important, to begin with, but nevertheless, form a mosaic of settlements in the province.

Many of these villages and small towns, now, may have been important sites in the past; it’s only by going through the meticulous work of authors like Sheikh that one gets to know of the significance of the place which is now not very important or talked about. But the remains or the continuous settlement over centuries spread an even light on the history of the land mass itself.

Since most of the history of the land has been in the oral tradition with very little being actually documented in comparison, such writings, too, have shades of the oral tradition in them.

It was not so long ago that there would be a group of elders who’d know the history of the place or the personalities that were associated with it. There may be just one of those wise men left -- advanced in years losing his eyesight and hearing ability -- that everyone in the village may be pointing towards as the chronicler par excellence. Very few of such characters are now left and so the younger generation in comparison is illiterate about the history and its lore.

It is important to point out that the oral tradition can be subject to change for a number of reasons, least being the memory and its lapses or most, the instinct to dramatise and make the most of the moment by exaggeration. Oral history was not narrated in an objectively detached manner and histories or chronicles carry the shades in plenty of the requirements of the oral narrative. Yet it is a minefield of information that may not always stand up to the scrutiny of an objective historian. But so little has actually been known of the various places, their development and lessening of importance with each age and its vicissitudes.

Being one of the oldest places that have been inhabited continuously over millenniums the land mass has many secrets hidden that need to be exposed or unearthed. These small towns have names that we know nothing about or on whom they were based, or the significance of an event that may in retrospect not have appeared to be earth-shaking. We do not know about the process or are too obsessed with the end or the final output.

The various stages usually become the victim of oversight, or simply ignored. In Punjab, too, the settlements were named like pur or pura ( which according to the author is Sanskrit for mud wall that was made around the village), waal , wala or wali (to whom it belongs), kot , kotli or kotla, (for fort) khel, (pushto for a tribe) ki ka key, yaan (it belongs to him or her or them), trinda (saraiki for dera), and the more commonly understood and used -abad, pind, pindi , garh, garhi, nagar, mandi, dera, watni, hujra, haveli.

For example, some were named after the founder; like Kamalia after Kamal Khan Kharal; after kings, like Jalalpur Jattan after Jalalud Din Khilji, Seetapur after Sita Rani; some after Sufis, like Hasan Abdal after Wali Qandhari; after tribes, like Gujranwala, Gujrat, Gujjar Khan Gojra from Gujjars; some on a geographical location like Daska from dus koha, for Sialkot, Pasrur, Gujranwal were each ten Kohs from here; some named after trees like Shakargarh from nishkargarh, sugar cane in Sanskrit, Layyah from a bush laye, Okara from a tree ookaan. Many have changed, altered or been corrupted with time like Phalia from Alexander’s horse Besophalia, Taunsa from Taoosa, Rawat from Rabat, Taxila from Taksheela, Mandi Bahauddin from Pindi Bahauddin and so forth.

Many names have been changed or Islamised like Lalyani is now called Mustafabad. Usually, people hailing from these small towns and villages have much to say about their places and families but no one is willing to pay any attention to them. They find solace in merging with any overbearing identity, but the villages and the people with their castes, identities actually form the raw material of their history or the history of the land.

Many have written about the history of the various castes and families but it has not really been allied to the land and the place. The two have, as it were, dealt with independently of each other as if comprising two streams. The necessary connections have not been established, and thus the true ownership fails to get authenticated. This book has attempted to do that.

Asad Saleem Sheikh belongs to Pindi Bhattian and is the chairman of Dulla Bhatti Sangat. He has been given numerous awards for his various writings.