It is important to recognise that far from being a "disputed territory", Kashmir is a story of a people demanding their right to self-determination amidst the power politics of two postcolonial nation-states

Last week, India and Pakistan were at the brink of war. This week, as it appears that both countries have taken a step back from the dramatic escalation, life in Kashmir, on both sides of the Line of Control, remains the same -- a cycle of death and destruction that has no end in sight. Indeed, as the aftermath of Pulwama resulted in the rapt attention of the international community on developments in the region, and as some Indians and Pakistanis took to social media to declare #saynotowar, the experiences, perspectives, and aspirations of Kashmiris, already living in the status-quo of war, were completely ignored. Yet, this is nothing new.

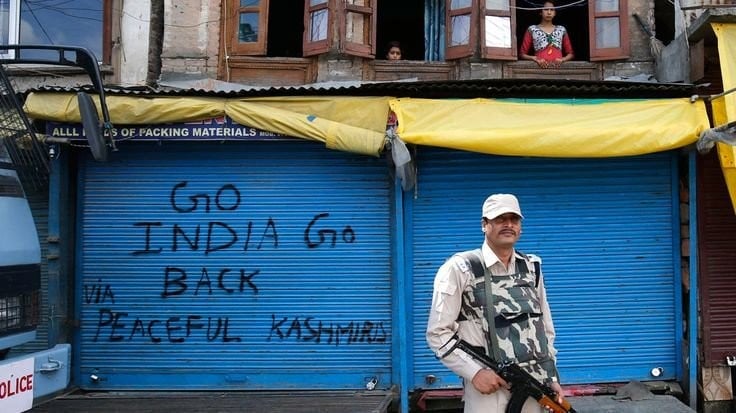

The Kashmir issue continues to be depicted as a "territorial dispute" between India and Pakistan, two nuclear powers that threaten to erupt into war from time to time. What has been made clear over the past few weeks -- and what Kashmiris have been demanding -- is that any conversation about "India and Pakistan," must centre the occupation of Kashmir. It is important for all parties involved -- including both Indian and Pakistani liberal elites -- to recognise that far from being a "disputed territory" or a simple "conflict zone," the story of Kashmir is one of decolonisation, a story of a people who have been demanding their right to self-determination amidst the power politics of two postcolonial nation-states.

To speak of "alienation" or "separatism" is to assume that there ever was a sense of belonging, either political or affective. This is what separates Kashmir from other "restive" regions in the subcontinent -- the Northeast in India or Balochistan in Pakistan -- and thus, it becomes disingenuous to invoke Kashmir within the context of "ethnic" or "minority" mobilisation. To speak of "terrorism," also, is to distract from the root issues: a political occupation and structural state violence. It also does not apply when the attack was directed against armed Indian combatants, not unarmed Indian civilians. Before yet another generation is lost in Kashmir, the time has come for the international community to put pressure on all parties involved, privilege Kashmiris on both sides of the LoC as agents of their own future, and pave the way for an end to the occupation and eventual self-determination.

Given that the Kashmir issue only makes international headlines when an attack like the one at Pulwama occurs, it is easy to conclude that it is these acts of violence by non-state actors that define what the trouble in Kashmir is. What is overlooked is that the last year, 2018, was the bloodiest year in the region in a decade, as nearly 600 civilians, rebels, and Indian armed forces were killed. These deaths and killings exist in a continuum of state violence and repression against a population that has vehemently rejected Indian rule.

The death of the popular Kashmiri rebel, Burhan Wani, in 2016, reenergised the new wave of youth resistance that was on the rise since 2008. Since 2008, an entire generation of Kashmiri Muslim youth, who came of consciousness during the militancy of the late 1980s and ‘90s, has taken on the Indian state, both online, and on the streets. Dubbed by analysts as the "new intifada," Kashmiri youth protest what they call the Indian occupation -- the presence of nearly 700,000 Indian armed forces in their land as well as the lack of political self-determination that has led to their forcible incorporation into the Indian nation-state since 1947.

Initially, the protests were peaceful, as large crowds would gather to protest fake encounters, land transfers, human rights violations, and cases of sexual violence, demanding an end to the occupation and the right to a plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s future. As the protests grew in momentum, the Indian state responded brutally, firing live ammunition into crowds, arresting political leaders and youth activists, and oftentimes, declaring shoot-on-sight curfews in the region, in order to prevent further protests from occurring.

Massive protests slowly gave way to smaller-scale street protests, as young men threw stones at the army that was deployed in their area. As Kashmiri youth began to see their peers getting killed, arrested, or injured, a handful began to join militant ranks, creating a new form of "home grown militancy" that has differed in size, scale and composition from its earlier iteration. These armed rebels, whose numbers have never been more than a few hundred, are usually local youth who have witnessed or experienced some form of injustice, as was the case with Adil Ahmad Dar, the Pulwama attacker. They are largely untrained, unlike the rebels in the decades prior who would cross the LoC and get trained in Pakistan. Their life span is short; within a few months, or even days after joining, they are killed.

The latest iteration of the uprising began before Modi came to power in India, and was also brutally dealt with by the Congress government. However, the Indian government under Modi has become more hardline -- there is no space for dialogue or engagement; instead there is only the lethal mix of Hindutva nationalism, flexing of military strength and complete elimination of Kashmiri resistance.

Also read: A thorny path but the only one available

With the emerging elections, Kashmiris fear that even worse will happen. Most crucially, they are worried about the fate of Article 35A and Article 370, provisions within the Indian constitution that give Kashmir a "special status," and ensure that any provisions that are introduced in India, can only be introduced in Kashmir through the state government. Article 35A leaves it to the state government to define who is a permanent resident of the state, and also does not allow non-state subjects to buy property in the state.

The BJP has repeatedly threatened that it will revoke these articles, which, as a number of scholars say would actually cut any provisional hold India has over Kashmir. However, the BJP sees it as an opportunity to change the demographics of the region, and introduce Indians from mainland India to settle into Kashmir, a policy that it utilises to mobilise its Hindu nationalist base.

The Pakistani state under Imran Khan is interested in renewing dialogue with India, a step that Kashmiris welcome wholeheartedly. However, given the current state of political affairs in India, this remains unlikely. It is the Kashmiris, then, that will continue to bear the brunt of this political impasse.