As Manto interrogates both language and practices of the colonial power in many ways, his stories show that the ‘margin’ can speak to the ‘centre’

How a writer develops his relationship(s) with authority and power is primarily a question of political nature. The moment a writer allows his imaginative realm to touch upon layers of outer, institutionally organised, narrative-ridden, value-bound world, a sort of political engagement ensues. A writer has an edge in working out this kind of political engagement -- not just because he can exercise the power of his imagination over the ‘power’ being practised in the outer world in a host of ways, ranging from pure linguistic and stylistic to ideological ones, but also due to being cognizant of the distinctness of power of creative language that presents itself in the face of crude political power.

It needs to be stressed that not all writers come to look at the distinctive nature of language in the same way. There are writers who try to work out a sort of conformity between language of power and language of their writings. By this they opt to stabilise, strengthen or favour the existing system of power -- colonialism in the present case.

But there exists another cohort of writers -- among them Saadat Hasan Manto is the most significant figure -- who reject any possibility of convergence of language of power and power of their language. So, they not only find themselves at an advantage in the work-out of political engagement but start interrogating power, its language and practices.

Manto interrogates both language and practices of colonial power in many ways. Sometimes, he writes on the effects of colonial policies on the low strata of colonial India (as in ‘Naya Qanoon’), at other times he narrates the life under colonial rule in subversive way. In his stories, he seeks to de-centre the claim of centrality of colonial power, in a somewhat queer way, by choosing his protagonists from the marginalised segments of society, allowing them to assert their humanity by circumventing all efforts to put them in dehumanised conditions. His stories show that the ‘margin’ can speak to the ‘centre’.

Manto is also the first Urdu writer who narrated the story of transition from British colonialism to Neo-colonialism (American) by writing letters to Uncle Sam in the early 1950s.

Colonial binaries and their subversion

Colonial discourse is deeply embedded in binaries. Europe/Asia, West/East, coloniser/colonised, universal/local, English/vernaculars, rational/superstitious, modernity/tradition etc are just a handful of binaries that can be located either beneath or ingrained in colonial discourse. They serve not just to differentiate the West, universal, English and modernity from the East, local, vernacular and tradition; rather they are there to establish a system of hierarchies in which all that fall in the first category is superior to those comprising the second category.

So, in the colonial discourse, West, coloniser, universal, English and modernity occupies a central, hegemonic place -- not only an epistemological position to define the East, local, vernacular and tradition but a political power to relegate everything related to the colonised to the margin. This way centre/margin binary acquires a status of meta-binary.

Magical realism is played out in multiple ways. Sometimes it is confined to the confounding past and present; at other times, it goes on adopting a vexatious use of language and in some cases it rewrites -- partially or wholly -- old, forgotten, silenced, marginalised stories.

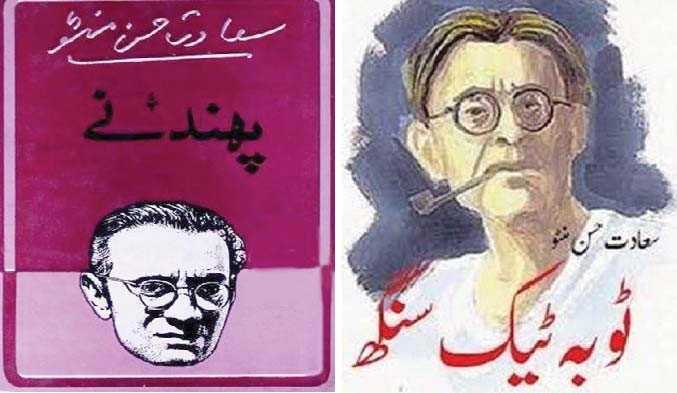

Manto hits out at this meta-binary. Instead of showing resistance against small sets of binaries, he aims to subvert the mother of all binaries -- centre/margin. In ‘Inqilab Pasand’, ‘Sooraj K Liay’, ‘Naya Qanoon’, ‘Batain’, ‘Boo’, ‘Toba Tek Singh’ and other stories, he goes on destabilising the centre’s rousing claim to define and delimit the margin by making the latter reclaim her authentic voice that was silenced and distorted by the former’s hegemony.

Destabilising the stable self

Development of ‘Modern Urdu fiction’ tells a story of conformity and resistance. Its inception owes itself to colonialism. It was the colonial administrators who encouraged indigenous writers to produce ‘new, realist stories’ that could be made part of school curricula. So, the earlier instances of Urdu novel written in late 19th century seem to eulogise conformist, obedient male and female figures presenting themselves as ‘role model’ for the youth.

Moreover, the earlier fiction writers took upon themselves to portray a realist picture of the ‘linear progress’ of events, reform agenda of colonial education through characters having a ‘stable self ’-- not surprising to note that only a conformist character can claim to have stability of self. Realism to some extent and stable-self to a greater extent served the colonial purpose. Dependence on realism, on one hand, forces a writer to see just one, usually brighter, ‘enlightened’ side of reality and on the other makes him believe that language is a transparent medium -- a naïve concept that suppresses the mediational role of language.

While the stable, unquestioning self becomes a faithful medium for transporting (colonial) ideology; it does keep intact his ‘stability of character’ by not raising eyebrows at what happens to him (at the hands of colonial forces), staying calm and attributing everything to destiny or qismat, nor turns eyes to the inner world where nothing is stable or unwavering, where there are dark forces defying ‘brighter, enlightened’ narratives of life.

In this backdrop, surrealism emerges as an anti- and postcolonial phenomenon. It believes that what we call human reality and which fiction attempts to reveal is essentially multifaceted, obscure, wrapped in darkness. Some of Manto’s best stories are surrealist though mostly partially; they confound rational/conscious/ social/political/colonial and irrational/unconscious/personal/local elements into the ‘new, imaginative reality’. For instance, in ‘Toba Tek Singh’ the phrase Oppar the gurgur de annex the bedhiana de mung de daal of the Pakistan government (last two words are afterward replaced by Toba Tek Singh) …. repeated by the protagonist of the story Bishan Singh is surrealistic in nature -- interweaving the irrational with rational, conscious with unconscious, and personal with political in a way that resists simple, single, rational interpretation; yet opens up a window onto the complex, distorted, divided and tarnished world of colonised people.

In this surrealist line, the word annex has deep political connotations. How a real motherland of Bishan Singh can be annexed to an imagined, new born country and turning it foreign to him, was so perplexing a question which wrapped his total being.

Cultural dementia and magical realism

As a common structure can be found beneath all, diverse forms of colonialism (practised in Asia, Africa, Latin America), so a shared strategy to deal with the colonial problem can be seen among the postcolonial writers belonging to different regions, languages and periods. Things like imposition of silence and forging cultural dementia can be reckoned as chief characteristics of colonial structure. Magical realism sprouted as a form of resistance against imposed silence and forged dementia.

Interweaving of the magical with real, natural with supernatural, reality with fantasy in stories was in reality an attempt to break the silence and dispense with cultural dementia. We know, as the silence is broken, a concatenation of voices (out of known and unknown regions of psyche, in this case out of collective psyche of tradition) begin to pour out -- a sort of multivalence, an essential feature of postcolonial fiction. In Manto’s ‘Farishta’ and ‘Phundnay’, Qurratulain Hyder’s Aag ka Darya, Intizar Husain’s ‘Nar Nari’, Surrender Parkash’s ‘Bijoka’, this multivalence seems to spawn out of the melting borders of reality and fantasy.

Magical realism is played out in multiple ways. Sometimes it is confined to the confounding past and present (as in Aag ka Darya); at other times, it goes on adopting a vexatious use of language (as in ‘Phundnay’) and in some cases it rewrites -- partially or wholly -- old, forgotten, silenced, marginalised stories (as in most stories of Intizar Husain).

The overall purpose of magical realism seems to be to do away with epistemological violence caused by the colonial world’s claim that empiricism and realism are the only authentic ways of capturing reality. Mind it, magical realism doesn’t outrightly reject realism, rather it breaks the binary of real and fantasy which wards everything off that appears or might appear to contest what is presented as real.

In magical realist fiction, the binary of real and fantasy is broken in such a way that none of them is in a position to claim superiority or exercise hegemony. Imagination is believed to be a more reliable, more powerful source of creating reality as the mind is taken as a trustworthy means of conceiving reality -- an attempt to assert the whole being of postcolonial people.

Colonialism’s notorious binary of East and West is also done away with in the same way because the magic of Eastern traditional fiction is ingrained into the Western form of novel and short story. What was displaced, i.e. Dastan, Hikayat, myths, is reclaimed -- not revived.

While reading the postcolonial literature, a line must be drawn between revival and reclamation. Notion of revival is steeped in a wish to bringing back the old, lost, golden period which is glorified simply because of its having existence in nostalgic memories. While the concept of reclamation arises out of the realisation that past cannot be revived in totality but partially, it can be sewn into the fabric of the present by interpreting it and extracting its significance that outlives time.

Manto’s ‘Daikh Kabeera Roya’ is a fine example of reclamation. In this short story, Bhagat Kabir is shown visiting different parts of Pakistan and on seeing how humanity is being massacred by zealots starts weeping. To Manto, it seems, Kabir, a 15th century poet-devotee, is an indigenous prototypal image of humanity, defying all kinds of discriminations, divisions, hatred and violence. Kabir weeps when he sees the book containing poetry of Surdas being mutilated, the idol of Laxmi being veiled, the armies of both sides engaged in war and religion being forcefully imposed. He weeps because no one is there to listen to him.

Both ‘Farishta’ and ‘Phundnay’ were written after independence, in the postcolonial era. Both diverge from the style, technique and of course themes that Manto himself had been employing in the stories written before independence, in the colonial era. These stories tell that the conditions inspiring Manto’s imagination have altered significantly. Not that the so-called dream of freedom from colonial rulers has been fulfilled and a new, emancipated world has come into existence; instead, reading these stories we come across the ‘fact’ that a more complex, far perplexing, much confusing world is there to be understood through ‘our, own ways’.

These stories also tell that political freedom from colonialism doesn’t guarantee true, complete emancipation. A long, multifarious struggle is still required. In both these stories, written in magical realist style with a non-linear plot, the protagonists are shown struggling for their emancipation in uncanny situations. In ‘Farishta’, the identity of Farishta (doctor) is unspecified. Attaullah, a patient admitted to a hospital is unable to come to know whether the doctor is Farishta-e rahmat (angel of blessing) or Farishta-e ajal (angel of death)? He sees multiple images of his own and fails to conclude which one is real and becomes helpless in distinguishing the real from that of work of fantasy -- entangled in a multivalence. He kills his own son which is also symbolic; he kills him whom he had given birth.

In this story, from ailment to hospital, to a doctor to killing his son and to multiple images, everything is pregnant with metaphorical meaning(s), which can be interpreted in the postcolonial perspective. It is not difficult to understand which place can qualify to be called ‘hospital’; who is ailing and why he is seeing multiple images that seem to refer to specters and ghosts. Also, it is not hard to know why the identity of the doctor, traditionally known as Messiah, remains unspecified? Similarly killing his own son connotes those effects -- in the form of specters -- of brutality exhibited at the birth of a new nation that keep haunting an ailing Attaullah, literally meaning benefaction of God.

‘Phundany’ also features a struggle in an uncanny, postcolonial world. In this story, a female painter undresses herself and paints her nude body. The tassels she paints on her neck strangle her in reality. Both stripping off (colonial) dress from her body and painting it has a sense in the postcolonial world. Her death caused by painting of the tassels is fantasy, but not a hollow fantasy; it is full of deep meaning. She painted the same tassels wearing around her neck in reality. Producing replica of (colonial) dress caused her death.

This story implies that entering the postcolonial, free world requires the death of legacy of colonialism on one hand and on the other a new birth or reclamation of indigenous world, languishing in wreckages of dementia.

The writer is a Lahore-based critic, short story writer and author of Urdu Adab ki Tashkeel-i-Jadid (criticism) and Rakh Say Likhi Gai Kitab (short stories)