The film fails the politics of representation, but pushes the politics of craft

One of the first scenes in Gully Boy is a confusing, but exciting one. Murad (Ranveer Singh), the underdog poet/rapper of the movie, who lives in the slums of Dharavi, is standing by the entrance of his house, watching a man (his father?) walk in with a bride. As the people in the gully make room for the couple to pass, Murad stands fixed on his spot, and plugs in his earphones. The rap song he is listening to grows louder, drowning out the wedding music. We, the audience, slip into his feet, listening to the music with him, zoning out his surroundings. We do not completely understand what is going on -- Is his mother dead? But didn’t we see her two scenes ago? -- but we trust him. We trust that it will make sense; for the moment, we are present with him, moved by the distance he feels.

This is not a usual scene in Bollywood. It lingers without explanation. It does not effectively serve its plot-point, the father’s second marriage, which could have been relayed through quicker dialogue. It is too empathic, too realist, and realism is not a quality one associates with Bollywood.

Growing up on Bollywood, I have known it as the site of impossible truth-bending. A world where natural laws can be defied in the service of a masala script, where the wildest twists can be smoothed out to result in a happy ending. Dead people can come back to life, pills inserted inside paans can impregnate people. Bollywood is founded upon exaggeration and absurdity, on rules that are stripped of their fidelity to the real world. The same applies to its characters, who do not behave naturally, they are superficial at best, if not completely un-human and unreal.

Watching Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham, for instance, there is the acute awareness that this is Shahrukh playing Rahul or Kareena playing Poo -- we are never really convinced that Rahul and Poo are real people who actually talk like this, because it is difficult to distill the character on-screen from the superstar celebrity playing at them, and because real people do not dramatise and over-explain. In K3G and most of Bollywood, characters are expository and one-dimensional. They voice their ulterior motives, they help make connections in the plot-line, they lack depth, and move only in service of the script. There is zero breathing room where the audience can actually, meaningfully connect with the character on-screen. In short, there is no room for a scene like Murad watching the street, standing by with his earphones.

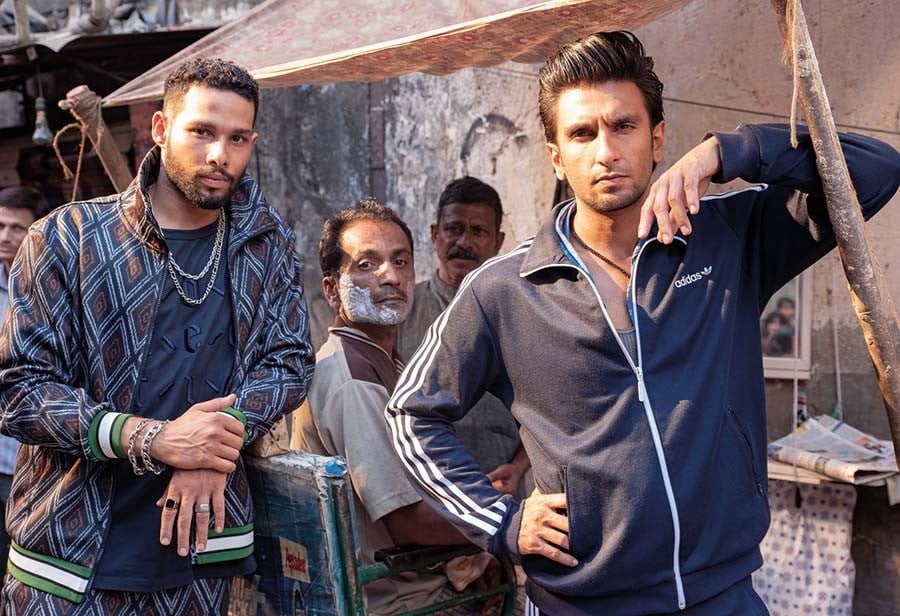

Which is how Gully Boy raises the bar. It is full of quiet scenes that do not necessarily further the main plot, but allow us to linger in the characters’ lives. Murad and Safeena (Alia Bhatt) romancing in the bus; Safeena being scolded at home; Murad and his friends smoking up on the bench; MC Sher (Siddhant Chaturvedi) with his alcoholic father; Murad writing by himself at night. Zoya Akhtar takes us through the different spaces these characters inhabit, stitching the narrative through banal spaces of routine; she connects us to these characters by letting us experience their everyday moments of intimacy. Important revelations and plot-points are shot with the same matter-of-factness of a day moving ahead: Murad folding the towel before placing it back in his rich friend’s bathroom; Murad having dinner with his family in the new apartment; Safeena crying by herself. Gully Boy’s characters feel real and believable because we witness their lives through their everyday.

As we see these characters in different spaces and settings, we start to think of them as multi-dimensional. We see how different parts of them surface on different occasions, how nobody is attached to a single concern or plot-line. Their decisions and contradictions are convincing because they exist and behave like real people; moving in multiple places, juggling the different parts of their lives, channeling their frustration from one relationship into another, now warm, now inexplicable, now familiar, now unpredictable. We are moved even when they mess up, because just like real human beings, they do not exist on a single pitch. Murad is more than his rap, Safeena more than her relationship, and Moeen (Vijay Varma) more than his drug-dealing.

By humanising its characters in this way, the film also humanises their identities. They are not a caricature of the gender, religion or social class they represent, unlike typical Bollywood movies, where a woman is only concerned with her love life, where the Muslim character is obsessed with Islam, and the poor character only complains about her poverty.

It helps that the characters are not typecast, of course. Murad is not the macho Bollywood hero blindly following the family’s parampara, but a humbler, more tender individual, who uses his gender privilege only where he needs to take a stand. Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti have ushered in a new kind of hero, one who isn’t necessarily un-masculine, but whose masculinity is also grounded in his emotional power. Then there’s Safeena, a complicated, unforgiving heroine who is neither the bad girl, nor the virtuous Parvati. Her moral compass is sketchy and unreliable; she is caring, but also jealous and possessive, even violent. What is key here, is that she does not carry the burden of being the perfect, supportive, submissive girlfriend, nor the burden of representing all of womankind: she is her own person, and therefore, once again, a real person.

The main characters are all Muslim, but at no point is that all they are. It is impossible not to compare Gully Boy against the scores of movies which have always shown Muslim characters glued to the prayer mat, or speaking in a stream of Mashallahs and Inshallahs, or brandishing tasbeehs just in case we forget their Muslimness. Murad goes to the mosque in the same way he goes to rap circles; Safeena takes off her scarf when she like without making a big deal out of it; and not once does the Azaan blare in the background. For Muslims in Gully Boy, Islam is part and parcel of their days but it is not the only thing that defines them.

Similarly, class is present everywhere, but it is not constantly named. It is present visually and experientially, through the slums Murad and his friends live in, through the clothes they wear and the spaces they hang out in, through Murad’s job as a driver, in the toxicity of his family’s circumstances, in the weight of his responsibilities. It is present in his relationship with Sky (Kalki Koechlin), in his gesture of covering his face when a white tourist photographs him, in the nights he tries to record music without interruption. Class is a shadow that falls on Murad throughout the film; and while his life is not just about class, but also love, friendship, dreams, ambition, the film shows the nuances of how class intersects with each of these themes.

For once in Bollywood, class is not demonised, it is not evil or morally corrupt. Most interesting is the character of Moeen, who ‘uses’ young boys to peddle drugs. In a poignant scene, Murad is screaming at Moeen for making the boys do his dirty work, and Moeen replies: At least I give them a roof over their head. Would you rather they be abandoned? This is a moment where the audience checks their class privilege. I know I did: in judging Moeen and limiting him to a single context, I realised I had reduced his identity to the poor, fallen drug-dealer, permitting no room for the caring guardian. I had failed to empathise.

Which is constantly what Gully Boy is asking you to do, especially in terms of class, making the middle/upper class audiences aware of their gaze. The tourist scene, for sure, where they are teeming through Murad’s family’s house with exclamations of ‘How exotic!’ But also the character of Sky: the well-meaning but still-ignorant elite friend who helps Murad make a music video. Sky is a critique of the English speaking, study-abroad brand of social justice activists whose generosity aids their personal gain, and who are often blind to their own problematics. Many of us will be made uncomfortable by the character of Sky because we will see ourselves in her. In the graffiti scene, Sky spray paints radical-sounding slogans like ‘Brown + Beautiful’ but Murad paints ‘Roti Kapra Makan & Internet’ in Hindi. When they are recording the song, Sky tells Murad she is interested in him because she sees beyond his class, sees him as an artist. We don’t buy it. Through Sky, the movie suggests that even with all our good intentions, our idea of what is equalizing (art, maybe?) is grossly misleading. But perhaps we are made most aware of our class gaze in the song ‘Doori’ when Murad/Ranveer looks directly into the camera, breaking the fourth wall, reminding us of our own complicity.

Despite these undercurrents, Gully Boy has still been critiqued for its class politics. Specifically, how it sells the individualistic, neoliberal dream of ‘making it’, that if you work hard enough, you will get there. While the movie does promote this trajectory, I think it offers a subdued version of the usual rags-to-riches story. It is only in the second half that the Nas concert presents itself as an opportunity, and globalization offers its fruits to Murad, his sweet escape out of poverty. To even get to the point where Murad has the confidence to audition, he is helped by very different powers: social media and community. Murad’s early journey into hip hop and rap is mediated through Facebook, a capitalist agent sure, but also a democratising tool for a poor kid in the slums; and Murad’s rise to prominence is fueled by the unwavering support of the hip hop community, by MC Sher and his tribe. It can be criticised as unrealistic, such unconditional, pure loyalty and support, or it could be seen as a hopeful, positive re-imagination of social norms in a cinematic milieu that thrives upon villains who are waiting to ruin the protagonist’s plans.

Still, not everyone is happy with Gully Boy. Yes, it reinforces the neoliberal myth, the false idea that passion alone can carry you through. It waters down anti-establishment politics, by co-opting the Azadi slogan and editing it to make it more digestible. And it erases the chant’s link to Kashmir or JNU. Meanwhile, Gully Boy’s superstars are certainly not helping matters. Alia Bhatt commented that Safeena’s identity as a Muslim has nothing to do with her character. Zoya Akhtar distanced herself from the Azadi critique, claiming that the erasure was irrelevant because the movie is about economic disparity. It would have been better for her to simply admit that the film had its limitations as a commercial product. It would have been more honest.

But it would have been too much to expect from Bollywood. Gully Boy, and mainstream Indian cinema, exists only because of the neoliberal capitalist machine, and is not going to critique it. I personally feel Bollywood is not the site where one can place their hopes for politically responsible art. Maybe I am giving the film too much credit. I know I am biased because of my positionality; it is impossible to watch Gully Boy without measuring it against the lifeblood of Bollywood, without thinking of all the films I have consumed in my childhood, their stifling moral codes and unconvincing worlds. In light of that, Gully Boy feels to me a huge step in an exciting new direction.

Because even when lacking in nuance otherwise, Gully Boy has pushed the possibilities of mainstream Indian cinema creatively: basic questions of what constitutes entertainment, what a narrative looks like, how a story behaves. In an industry which looks down on realist cinema, even a film as promising as That Girl in Yellow Boots fails the imagination by forcing the plot to fall into place. I am not suggesting that exaggeration and absurdity are unequivocally unimaginative, but in Bollywood they have become staple, and therefore lazy. Gully Boy rejects popular cinematic traditions in Bollywood for realism, opening up possibilities for better, more emphatic representation in art: its streets are populated with characters who behave like real people, in a world whose rules we can rely on, in a story that genuinely moves because the script serves its characters and not the other way round. The film does not condescend towards its audience. It allows us to care for Murad’s world, not by explanation but by empathy. What about the politics of empathy -- not just through representation, which Gully Boy has rightfully been critiqued for -- but through craft? By lingering on everyday scenes and dialogues and writing multi-dimensional characters, Gully Boy has shown how to humanise the people we would never know, foster connection through banality and vulnerability, make us aware of our gaze, and open up room for empathy. Empathy politicises art. And all other failures aside, advancing new ways of empathy in Bollywood fundamentally alters what we can expect from mainstream cinema.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the Encore section of The News on Sunday