Sehat Sahulat-Insaf Cards could cover a majority of the people but a downside of a limit is that unscrupulous hospitals will deliberately exhaust the limits

For most of my professional life in the United States, I dealt with patients with some form of health insurance. Even I had medical insurance and carried an ‘insurance card’. In the US there are basically three types of health insurance; private health insurance, government insurance for the elderly (Medicare) and government insurance for the poor or the disabled (Medicaid).

As the US gears up for its next general election less than two years away, a big political issue that will likely become a part of the Liberal-Democratic Party agenda is going to be a government-run health insurance system for all US citizens.

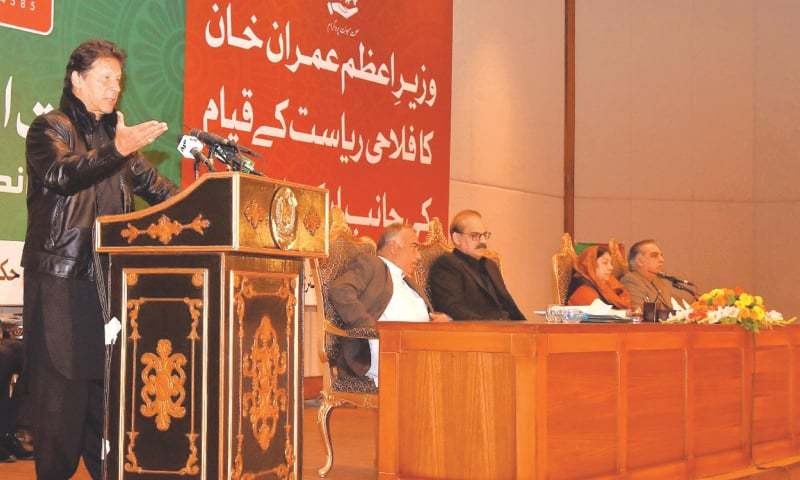

As a political liberal, I strongly support free or heavily subsidised healthcare for all citizens. Healthcare for ‘all’, as I have said before in these pages is a right rather than a privilege. As such I support the ‘health card’ scheme being initiated by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government for the entire country. Though I vacillate between thinking of it as a glass half full or a glass half empty.

Complete details are not available as yet about this programme. What we do know is that over the next two years families with an income below the officially determined poverty level will be given health cards (Sehat Insaf cards) providing health insurance through State Life Insurance Company. This, if implemented, could essentially cover a majority of the people in this country. And official statements suggest that this programme will eventually cover all Pakistanis.

Eligible families will be identified through existing poverty alleviation programmes, especially the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP). In my opinion, identification of all those eligible for health support is going to be a major problem and there does exist a real possibility that many deserving families might not be identified.

The other thing we know is that each of these families will receive ‘free’ medical treatment up to the value of Rs720,000 a year. Also, this financial support will be limited to medical treatment that is provided in an ‘approved’ hospital. We also know that all sorts of treatment except organ transplants will be covered by this programme.

But the devil, as they say, is in the details. And the most important detail that we do not know is what a hospital can charge a patient carrying this card for a particular service -- all hospitals participating in this programme will have to charge patients uniformly for a particular medical treatment.

Based upon my experience with health programmes run by the federal and the state governments in the US (Medicare and Medicaid), developing these lists of medical services and an appropriate uniform fee for them that is accepted by all the participating hospitals is going to be a significant endeavour.

What is, however, going to be a serious disadvantage in this scheme is the limit for the yearly medical expenditure per family. For young people who are generally healthy, the yearly limit might work but for those who are older and are really sick and in need of serious medical attention over a prolonged period of time, a monetary limit on treatment can be a problem.

Enforcing a limit on the total expenditure for treatment can even be more dangerous in cases where real medical help is needed. What for instance happens when a patient is sick and during treatment, over a period of days or weeks while in the hospital, uses up the established financial limit?

Another downside of a limit is that unscrupulous hospitals may deliberately exhaust the limits, the bill for treatment and then refuse further help. During medical care in Pakistan, most private and even some public hospitals offer a so-called ‘financial package’ for a particular type of treatment or an operation. And if hospitalisation expenses exceed that package the patient and the family are forced to pay for any expenses in excess of those agreed in the package.

There is a possibility of this happening to many of the seriously sick patients under this scheme. I have even heard of incidents in ‘private for profit’ hospitals where the hospital refuses to release a dead patient’s body to the family until all excess charges are settled.

Another problem with the scheme is that there is no money set aside for doctor’s visits. It is well known that a significant percentage of medical problems can be treated in a doctor’s office. So, if a patient only gets free treatment in a hospital, every patient with a sore throat and upset stomach will end up admitted to a hospital.

More importantly, much of preventive and routine care that can prevent serious medical problems and cut down the need for hospitalisation will not take place if there is no proviso for paying for doctor’s visits. So who’d pay for routine medications for problems like high blood pressure or diabetes or the laboratory tests that might be needed to treat chronic medical conditions?

During my time working at Mayo Hospital, Lahore, we often saw sick patients that were beyond help because they never had any routine medical care. Typical examples were patients with strokes (paralysis) that never had been checked for high blood pressure or treated for it.

To make this scheme better, it should be possible to modify yearly financial limit based upon patient need. And a certain percentage of money in the scheme should be set aside for non-hospital medical care.

From a personal perspective, the more important news was that when the Punjab Health Minister Dr Yasmin Rashid announced this programme in Punjab, she also mentioned that the public health sector was being improved. This includes all the facilities starting from the basic health units (BHUs) to rural health centres (RHCs) all the way up to the rural hospitals to the major teaching hospitals.

The health minister also mentioned that physicians might be allowed ‘on premise’ private practice when working in government facilities. In my previous articles, I have mentioned the need to provide some form of private practice for doctors working in the government run rural and semi-rural health care institutions.

Perhaps a portion of the money from the health scheme can be used to pay the doctors for seeing patients in the BHU-RHC environment. This, in my opinion, will not only be an important step to cut down on future hospitalisation expenses but will also be beneficial in terms of preventive healthcare. It will also augment physicians’ income and attract well-trained doctors to these rural institutions.

I am cautiously optimistic about the health card scheme. It does need to provide outside the hospital medical care and it must go hand in hand with the improvement of the public healthcare system.

And if this programme is successful and is expanded to cover most people in the country it will become very expensive. With better healthcare people live longer and will then use more healthcare as they get older. That’s the way the system works.

The author served as professor and chairman, department of cardiac surgery, King Edward Medical University