The journey of the political Left

People’s aspiration articulated through political action and state’s priorities usually don’t converge. Even a cursory glance over South Asia’s political history Asia leads one to this incontrovertible fact. The plausibility of that divergence between these parallel streams -- politics of the people and the state apparatus -- cannot be ruled out in other regions too. In the case of South Asia, strictly, the regimes of Nehru in India and Z.A. Bhutto’s (ZAB) in Pakistan are often described as populist (a pejorative term with pro-people overtones like roti, kapra aur makan etc.).

However, the impersonal, invisible and amorphous ‘state’ in Foucauldian terms reigns in such initiatives of those leaders with incredible measure of success. Thus, people’s aspirations are translated into practical reality only to a limited extent. Despite Nehru’s secularist/semi-socialist vision for India, caste, class and religion are the most glaring socio-political realities. The same can be said about ZAB in the case of Pakistan. He tried to use socialist slogans but what actually transpired was quite the opposite. The ultra-right-wing politics gathered force, rendering secular parties virtually irrelevant. Even Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) under Benazir Bhutto was pushed to the defensive and forced to re-invent itself in the light of right wing, statist prescription.

It goes without saying that the covert support was lent to reactionary forces to move to the centre stage of Pakistani politics by none other than the state and its core institutions. Exigencies stemming out of the cold war era and the peculiar situation in the wake of the Afghan war were contributory factors in according legitimacy and strength to ultra-right-wing political trend in the 1980s. Thus, ideological unilateralism found a conducive environment to flourish and the left-wing politics had no option but to retreat to the margins.

Interestingly, secular political agenda and socialistic ideals were what quite a few parties and groups adhered to in the 1950s and 1960s. Most parties with electoral support base in either East Pakistan or smaller provinces (which then were parts of West Pakistan) did not subscribe to right-wing politics. But, within twenty or twenty-five years, we witnessed a complete transformation in Pakistani politics. Of course, the situation calls for a serious analysis by political historians so that it can be ascertained as to where and when exactly things were messed up by our political elite.

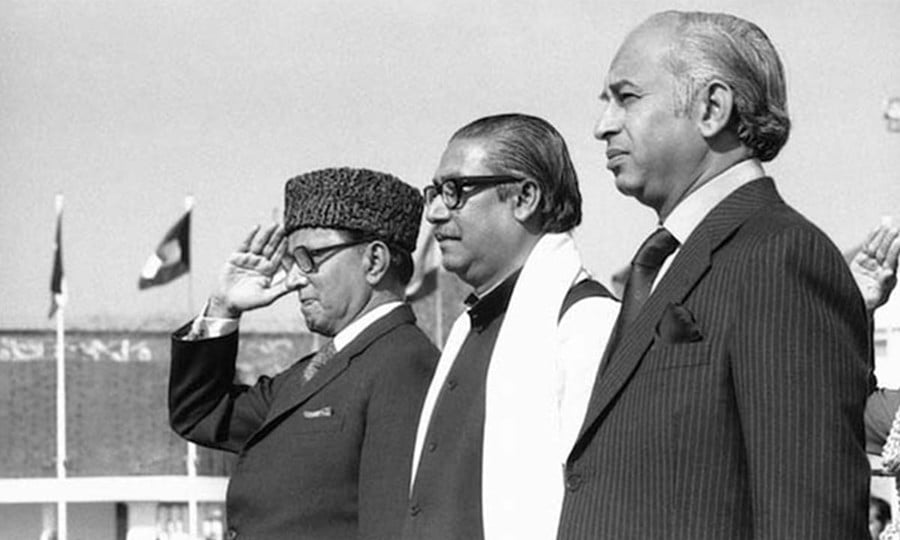

To my reckoning, barring the Mujib ur Rahman-Zulfikar Ali Bhutto duo’s obdurate animosity for each other which culminated into an impasse with disastrous consequences (undoubted the biggest tragedy in the entire history of Pakistan), clamping a ban on the National Awami Party (NAP) was the most condemnable act. Ironically, Bhutto for whom some of NAP’s ideals and objectives mattered a lot was responsible for banishing it from politics. NAP’s leadership was accused of treason and, after controversial trials, put behind the bars.

Before proceeding any further, it is pertinent to provide the context of the circumstances in which the NAP was founded. At the time of Pakistan’s independence in 1947, an organisation by the name of Democratic Youth League existed in East Pakistan which evidently had a leftist manifesto. Subsequently, the workers of this organisation came to identify themselves with the Awami Muslim League which was founded by Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy in June 1949. The Azad Pakistan Party in West Pakistan led by Mian Iftikharuddin was also known as a leftist party, and in 1957 it merged with the NAP.

The National Awami Party was brought into being in July 1957 by Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani and his leftist followers who had broken away from the parent Awami League in order to have a platform of their own. Over 500 leftists of various ranks from all over the country assembled at Dacca to form the new political party. The two main components of the new party were the Bhashani-faction of the East Pakistan Awami League and the left-wing Gajnatantri Dal (Democratic Party) which was founded initially in 1953 and, later, it joined the electoral alliance with the Awami League and Krishak Sramik (Peasants and Workers) Party to form the United Front (Jugtu Front) which put the Muslim League to a rout in 1954.

The main objectives of the new party were: an independent foreign policy, abrogation of military pacts, regional autonomy, dissolution of One Unit in West Pakistan, reorganisation of the West Wing into a number of provinces on linguistic, cultural and geographical basis, and the abolition of the Zamindari system in West Pakistan.

Also read: On the Left of political spectrum -- II

The creation of a separate political party was accompanied by the parallel formation of NAP parliamentary parties in the central and provincial legislatures. After passing through various phases, NAP had a tumultuous ride ahead. Internal wrangling and challenges from outside precluded it from finding a firm footing. Bhashani favoured Ayub Khan in the 1965 presidential elections, primarily because of his pro-China tilt whereas other leaders including Wali Khan threw their weight behind Fatima Jinnah. Until that time, a pro-China and pro-Soviet Union split within the NAP had become quite visible.

In 1967, the party split into two factions, one in East Pakistan and another in West Pakistan. That split not just weakened the NAP, it created a gap in Pakistani politics which provided a life-time opportunity to ZAB who founded his own PPP and filled that gap.

After the 1971 war, the Pakistani faction of NAP became the principal opposition party to the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto-led government of the PPP for which it paid dearly. Political differences between Bhutto and NAP’s leadership turned into those of personal enmity which wreaked disaster on the political culture and climate.

To be continued