Who are we if we don’t know our own history? Mudassir Bashir asks in his new novel

Mudassar Bashir, one of my favourites among the younger generations of Punjabi fiction writers from the west side of the border, has written his second novel, Kaun, the first being Samay, which I reviewed here several years ago. Prior to the publication of his recent novel, Bashir has published at least two well-received collections of short stories and several books on history, especially concerning Lahore. If readers were to have an opportunity to peer into Bashir’s heart, they’d have a difficult task discerning whether the heart belongs to a fiction writer or a historian. Inviting the historian within to accompany the novelist as he weaves a narrative can be a good or a bad thing, depending upon the result.

The title of the novel can throw the reader off initially, but eventually, the idea sinks in: Who are we if we don’t know our own history? Bashir seems to ask. Bashir’s two strong points as a writer are his interest in local history and keen observation of life as it unfolds among the working class and ordinary people. The latter gives a genuine lustre to the prose in his short stories. The novel is a different kind of a beast though. Bashir is aware of it and attempts to ground the novel in a political, somewhat philosophical terrain. Sarmad, the protagonist, wants to be an actor and pesters his close friend, Joseph the film director, for a chance. Joseph asks Sarmad to go through several scripts to find the one he likes and work on the role so the director can reach a conclusion as to whether his childhood friend deserves a chance or not.

Sarmad takes up the challenge and locks himself up in a spacious office with a huge wardrobe accommodating varied characters and roles. Each script Sarmad picks leads to two things: that it’s not easy to become an actor unless you have done a deep study of your character and a tutorial of the history of the profession or era. In each case, Sarmad gives up. But it’s the last script that really spooks him out. In his final attempt at convincing his director friend and himself of his ability to act, he decides to do a female role. Sarmad realises how hard it is to be a woman in the world, made toxic with masculinity. He alludes to women’s reduced worth in a patriarchal system by pointing out that the last script that he picks up with a lead female character was only "half written"; a point that is both very poignant and clever.

Having grown up on film sets in Lahore myself because my mother was an actor, I appreciated Mudassar Bashir’s inside knowledge of the studio culture and the way his characters talked; the studio lingo they used, rang true. It brought back many memories of having spent days and nights either silently watching the camera roll or loitering about the studio since every other person knew whose child I was, which lent a sense of safety. The dialogues of the characters who emerge from Punjab’s past history, as Sarmad gets into the skin of his characters are delightful, even if they are speaking modern Punjabi.

The reader is willing to allow Bashir a bit of poetic license here and there. The only problem Bashir runs into is when the historian accompanying the fiction writer becomes the rider and the writer his horse. The novel occasionally stops being a work of fiction and appears to be an exercise in historical exploration. There is nothing wrong with that, but the episodes are too small for any deep exploration and risk appearing didactic. It also limits character development. For example, we learn very little about Sarmad’s personal life.

The twin themes of the novel, the essence of acting or any art form and an average Punjabi’s lack of knowledge about their own history, are too heavy a material to be fitted neatly into a slim novella. Bashir is not alone in feeling frustrated about the fact that the Punjabis don’t read in Punjabi, for the primary reason that the language and its culture have been devalued in the minds of most Punjabis. On the one hand, our colonial experience has cut us off from our own history, literature and culture; on the other, our post-colonial rulers continue to show apathy towards this issue. Seen from this context, the title of the novel Kaun inverts Bullah Shah’s ki jaana mein kaun! into a sarcastic lament, almost, as if asking the reader and the writer collectively if they know who they are.

Like I said earlier, the novel is a different beast. In today’s world, it is not important to write a complete or successful novel, but the one that struggles with difficult questions, techniques, and tries to swallow bitter flavours. That’s the only way to arrive at self-awareness as a writer and a reader as well.

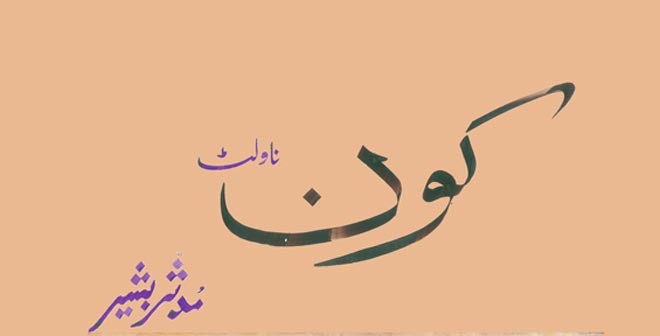

Kaun

Author: Mudassar Bashir

Publisher: Saanjh Publication

Price:Rs.200/-

Pages:250