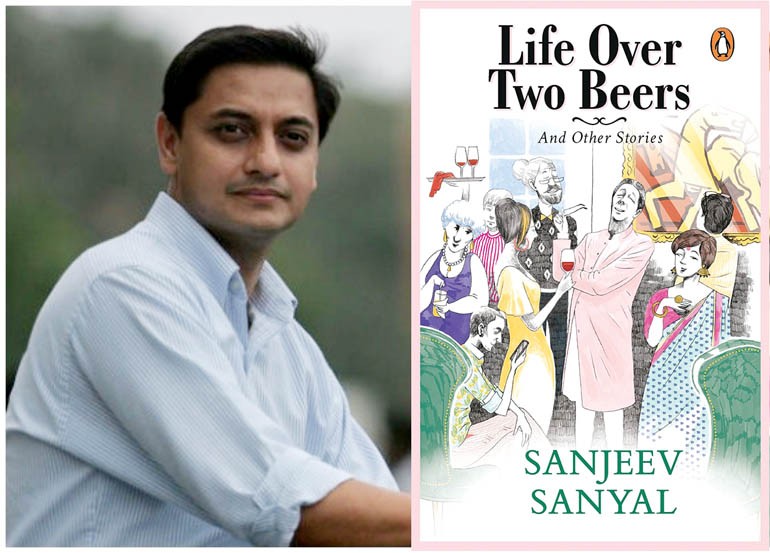

In a humorous take on Indian society, Sanjeev Sanyal makes astute points about the country’s shortcomings and fresh interpretations about its eccentricities

If the views of American fiction writer Lorrie Moore are anything to go by, short stories can be likened to love affairs because they don’t demand the same degree of commitment as a novel. As mere snapshots of a larger reality, they are constrained by timeframes and specific events, and often allow little room for lengthy expositions and complex subplots.

The short stories in Sanjeev Sanyal’s Life Over Two Beers and Other Stories break away from this mould by taking creative risks that may not appeal to all readers. More often than not, the ‘love affairs’ in this collection are saddled with long-winded passages that explain a character’s intentions before making any attempt to introduce them on the page as full-fledged individuals. The author’s preoccupation with telling more than he is willing to show, also makes these stories somewhat tedious to read.

But Sanyal’s words are embedded with the gift of wit and rare insight. Through these long-drawn-out explanations, he manages to offer sizzling insights into contemporary challenges in a perennially misunderstood country like India. As a result, his 13 short stories are able to push the parameters of how the world views the country’s moment of flux. Written with wisdom and empathy, Life Over Two Beers makes some astute points about India’s shortcomings and brims with fresh interpretations about its eccentricities.

However, it would be wrong to assume that these stories are pedalled by political polemics just because they paint a portrait of an evolving India. Sanyal’s work is peppered by social commentary and soaked with wry observations. The prime targets of his pen are elitism and intellectual snobbery. A witty, irreverent tone is maintained in every story and makes for a funny, insightful read.

In ‘The Used-Car Salesman’, the author examines how Rishi Taneja, an unsuccessful car dealer in England who returns to India to set his life in order, spins a web of lies to become part of an exclusive group of litterateurs. At first glance, Rishi’s treachery is driven by an impulse. With time, his meteoric rise seems to be fuelled by a faint desire for mischief, even though he clearly doesn’t put much thought into his lies. Although Rishi’s success draws hostilities from within the literary set, the graceless protagonist of this story realises that he can get away with his ruse so long as he has the benefit of good fortune. Rishi is the quintessential anti-hero who doesn’t always gain sympathy from readers. But his charming rascality and ability to penetrate an otherwise closed group offers a powerful critique on modern-day intellectuals.

A similar motif is adopted in ‘The Intellectuals’, where Sanyal revisits the power dynamics that exist within such groups. In crisp, humorous prose, the author writes about a foreign researcher’s experiment with a group of intellectuals in Kolkata. While this story mocks the yardstick through which these exclusive groups measure success, there is something crude and myopic about the perspective that the author brings to the fore with this story. On many levels, it comes across as slightly xenophobic and disparaging in an almost unfunny way.

‘Drivers’ is another narrative that builds on the closed-mindedness that elitism breeds. However, the subtler points of this story are lost amid the glut of characters and a weak plot. There are some gripping moments when Sanyal skilfully addresses the differences in local and foreign perspectives on India and its problems through well-conceived dialogue. But these moments struggle to salvage the overall effect of the story.

A more perceptive attempt to understand the blinkers that elitism imposes on people’s minds can be seen in ‘Reunion’, which shows how two college friends who meet after several years negotiate the material differences that threaten to separate them.

‘The Caretaker’ is another short story that stands out because it is told from the perspective of the ‘underdog’ rather than a person whose privilege keeps him from understanding social dichotomies. When a villager is appointed to guard the premises where a rural development programme plans to establish its office, he makes it a point to assiduously perform his duties as the caretaker. But fate and the government’s ever-changing policies bring him towards the stark realisation that his dedication and commitment mean little to the powers that be.

The other stories in Sanyal’s collection come across as somewhat half-baked because they rely on lengthy explanations that do little to make the stories come alive. Even the title story seems to lose focus and, therefore, fails to entertain.

A few poems have also been included in the collection. Readers may be tempted to ignore them because of their commonplace and slightly arbitrary observations. However, these poems ought to be viewed as much-needed intervals from stories that don’t always satisfy a reader’s curiosity. Each poem must be accepted as an alternative means of presenting the themes of this collection.

By turns clever and enticing, Life Over Two Beers makes you think and laugh in equal measure.

Life over Two Beers and Other Stories Author: Sanjeev Sanyal

Publisher: Penguin RandomHouse India

Pages: 223

Price: US$5.75