Of all the powers invested in the endgame leading to peace, Pakistan’s role is perhaps the most interesting to watch

The hints were all there in October 2018 when Mullah Baradar, one of the founding Taliban leaders, was released by Pakistan after having kept him in custody for eight years. At the time it did seem a sudden development but his possible role in the on-going peace process was acknowledged even then. And then there were reports of release of other Taliban leaders the next month, all in the wake of the meetings between Taliban leaders and US officials in Qatar.

With an almost categorical announcement of pullout from Afghanistan by the US, the talks led by their peace envoy, Zalmay Khalilzad, have assumed a new meaning, raising hopes about this seventeen year-long war coming to an end.

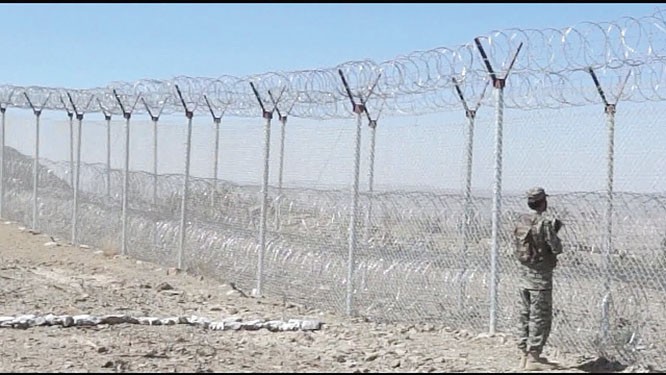

Of all the powers invested in the endgame leading to peace, Pakistan’s role is perhaps the most interesting to watch. It has, no doubt, facilitated the Taliban to come to the negotiating table, but the approach clearly reflects a change of policy that is geared to a destination that is galaxies away from its long-held position about Afghanistan’s future. So what led to this change of heart: have the external powers prevailed upon Pakistan or is the new policy home-grown; where do Indian interests in Afghanistan figure in this new policy; how central is China in this decision-making; and finally, what will become of Pakistan’s unilateral decision to erect a fence along the long porous border with Afghanistan, 900 kilometres of which is already complete.

Analysts are divided on framing Pakistan’s policy as a sudden "change of heart". Some like Brig. Mehmood Shah, former secretary security Fata, think "Pakistan had changed its policy with reference to Taliban about four years back; it decided to work with all the stakeholders in Afghanistan because it had realised after all this time that no single party could gain victory in Afghanistan."

This policy of non-interference, Shah says, "was being discussed since 2015-16, in various conferences of which I too was a part where it was said that Pakistan should be neutral in Afghanistan". This, he adds, is what has now been conveyed to the Taliban in the presence of the Americans "that they should sit in the talks and pay heed to any reasonable options".

Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Program at the Washington-based Wilson Center, in a way agrees with Shah. He goes to the extent of saying that the "US framework agreement with the Taliban is a validation of a Pakistani policy toward Afghanistan. Islamabad has long called for a negotiated end to the war, and now the US is trying to move quickly in that direction -- and apparently with some very big assists from Pakistan". He is referring to Pakistan convincing the insurgents to participate.

Clearly, this kind of future was not on top of Pakistan’s policy makers’ minds in 2010 when Mullah Baradar was arrested from Karachi. He is said to have engaged in secret talks with the Aghan government and "indirectly with the US and Nato forces" which was unacceptable to Pakistan then. In his recent op-ed for the New York Times, senior analyst and commentator Ahmed Rashid notes that Baradar "was a moderate on social issues and argued for maintaining relationships with the West and Afghanistan’s neighbours…. Mr. Baradar argued against isolating Afghanistan and cutting off all aid. He was aware of his country’s dependence on financial aid from the West".

So what are the recent compulsions for Pakistan to change policy, in Rashid’s view? "First of all, the military is finally convinced that the Americans want to leave; it’s a real thing that’s happening and they don’t want to be left out of the bandwagon.

"Secondly, there is a great deal of pressure from China because at stake are the whole CPEC and China’s huge investments in Afghanistan. Then the countries in the Gulf, too, are fed up with this war because they have suffered enormously because of drugs, money-laundering and extremism and they want an end to this sanctuary of extremists. Finally, there is NATO and EU and all the rest," says Rashid.

Pakistan’s foreign policy, for a long time, is said to have remained India-centric. During all these years, India has initiated huge development work in Afghanistan, creating a good will for itself while Pakistan was diplomatically, and even otherwise, isolated. How will the current situation bear on that? Ahmed Rashid thinks, "Indian interests have been hugely exaggerated by Pakistan. You can’t carry this clandestine covert warfare between ISI and RAW from one border to the other. There has to be a dialogue between India and Pakistan on Afghanistan and that could be brokered by either America or China".

He refers to India having no military commitment in Afghanistan and no contiguous border either, which can be blocked at any time by Pakistan. "They know their limitation and we should also appreciate that they have severe limitation regarding what damage they can actually do to Pakistan from Afghanistan."

Somehow, there is this sense in Pakistan that India is out of the game. A foreign office spokesperson even hinted this last month that India has no role in the peace process. Kugelman agrees that Pakistan’s "objective in Afghanistan is all about denying India space. So long as the Taliban don’t hold political power, that’s a tough goal to achieve given that non-Taliban Afghan governments tend to be quite friendly to India. But if an eventual agreement between Kabul and the Taliban leads to a new government that includes some type of Taliban representation, then the calculus could change in a big way, with troubling implications for New Delhi."

Also read: Withdrawal symptoms

So far, so good. Pakistan’s objectives seem clearly directed, except perhaps the fence it is making on the Durand Line. In Rashid’s view, it’s a disaster that "will antagonise Pashtun populations on both sides". Shah recalls the conferences discussing the future course of action for Pakistan where the only way to Pakistan to become neutral was by securing its border. "Thus it was decided to make a fence. But it needed Rs70 billion that were sanctioned by the government. I think it is a right decision."

Kugelman says, "the problem with the fence is that it risks antagonising Kabul, which thinks the fence is meant to legitimise a border that it has never recognised. There’s never been a more important time for Islamabad and Kabul to patch up their differences". Who knows what Pakistan may have to do with this fence after the final peace settlement? Who knows what the final settlement entails?