The young artists displayed at NCA’s annual degree show address a "confusion and anxiety" that a city like Lahore confronts regularly

National College of Arts (NCA) recently held its annual MA (Hons) Visual Art Degree Show for the 2017-18 session at Zahoor Ul Akhlaq Gallery. As per tradition, the December exhibit showcases the works of the college’s Master’s students while the upcoming January show will focus on those of Bachelor’s students.

As a conglomerate, the displayed works seemed to comment passionately on some uncertainty and confusion of metaphorically -- or literally -- ‘existing’ in Lahore. Sarah Mir, for instance, concentrates on the cacophony of urban mobility and sound. Her work makes use of a mixture of broad and stunted strokes to illustrate a city that fluidly melds into its people as they do into its environment, and so forth. Marketplace scenes are appropriately put under a painted layer of disturbance, of aesthetically opposing and disrupting forces and colours layered upon the strong skeleton of a bazaar.

The scattered, overpowering foreground of Mir’s work called to mind the technique of Mashkoor Raza. It is exciting and propels you to question: is this pure aestheticism or is it simply the representation of Lahori pollution? Fortunately, it may be both to its audience.

Huma Maqbool explores a similar scatter through her pieces. Her artist statement reads: "Uncertainty that arises in the disclosure of a reality inherent is what I am trying to capture in my work." She views this with skepticism. Her paintings depict withering or broken concrete corners of roofs and buildings.

This dialogue of the industrial urban space with its dishevelled, discordant observer seemed to serve as a prominent theme in this year’s show. Saif Ali Siddiqui characterised it in his work through elaborate, mishmash patterns that melt into one another, other objects, or members of the city -- from people to structures, and arguably, a lot that is uncertain in between. Siddiqui attributes the inspiration and content of his art to the nexus of his surroundings and his "post-colonial concerns." With his thesis display, he aims to incorporate his signature patterns into the historic spaces and images of his environment. Here too, the artist wills to address a "confusion and anxiety" that an urban city like Lahore confronts regularly. In the city’s postcolonial origins and its moulded development under a world submerged in imperialist culture, politics, and taste, Lahore is subject to these anxieties of contradicting aesthetics, ideologies, and futurisms superimposed on one another without much deliberation and care.

Hina Muhammad’s take on the topic is far more extreme (and perhaps, as much real). She mixes the mediums of painting, sculpture, and photography to construct life-like representations of "experienced spaces" -- walls contaminated and inhabited by moss, broken stones, and half-completed restorations. Her work is morbid, and her opinion on our urban condition is poignant and incisive.

To an observer, the exhibition may provide a pertinent (and unfamiliar) moment of reflection. What constitutes Lahore today? How does the city’s history interact with its present? What forces are responsible for implementing this present on the vast but decaying greenery of Lahore?

Of the remaining artists, Noor-Ul-Huda and Javed Iqbal Mughal brought my attention to the idiosyncrasies of our social reality and domestic cloisters. Huda’s work charts the private space and its leaking into the public space to develop the map of Pakistan’s socio-political dialogue and its impacts. The faces in Huda’s work are distorted but confident. Her style is unique and disarming, but often leaves an uncomfortable room for curiosity. In its most remarkable element, the eyes of Huda’s characters stand out and speak up. Her concentration is on the identity consequences of Pakistan’s political reality, using "hidden details that speak to the societal and cultural influences on us, particularly ones that came from being a woman." While some audiences (like myself) may be more susceptible to finding themselves ignorant to the subtleties of Huda’s work as it pertains to gender, the work seems often too defiantly obtuse and elusive.

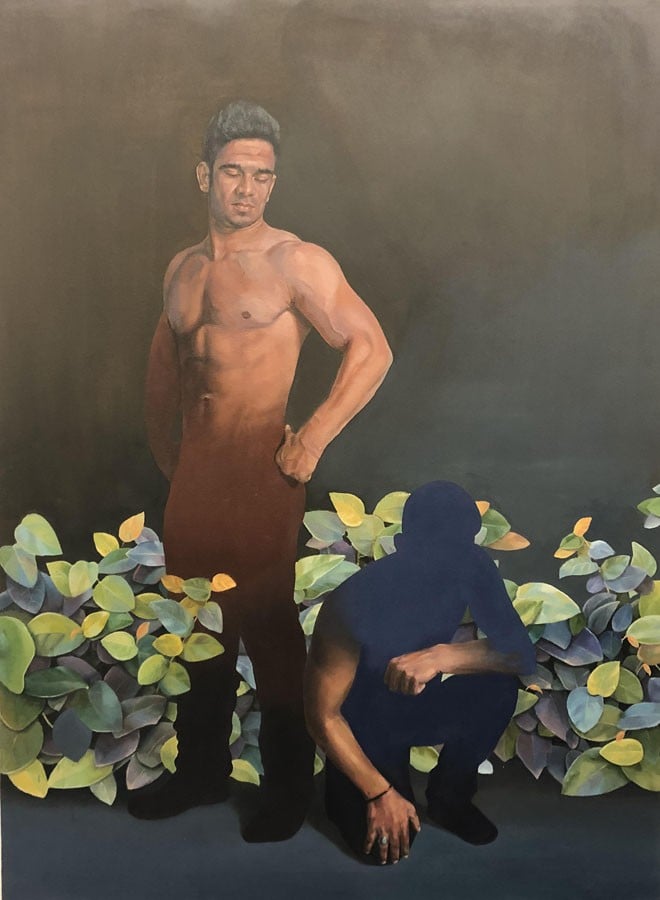

Mughal’s pieces attempt a similar, but more invasive, analysis of men and masculinity. His work explores masculine facial expressions to expound upon the silent conversations of hierarchy that exist unquestioned within our society. Mughal fades in masculine bodies within sinister negative spaces: his critique remains inwards. Ramzan Jafari, on the other hand, does not shy away from making his criticism macro-political, open, and direct. He targets in his voice the national issue of missing persons and enforced disappearances in Pakistan. He masterfully uses fabric, bukrams, aprons, and bones as proofs of missing people’s existence and burnishes (and sometimes, burns) these objects within layers onto each other. It is evocative and disconcerting, as artistic representation of an issue that merits it.

Lahore is seldom afforded the opportunity to reflect on itself through the expansive and intelligent channel of art, media and literature. In this dearth of creative and cultural showcases, the NCA annual Visual Art Degree Show provides to the onlookers of our city a unique but reliably consistent window into its heart and soul.