Does moving on from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle really mean improvement?

"To be governed is to be at every operation, at every transaction, noted, registered, counted, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorised, admonished, prevented, reformed, corrected, punished."

-- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

A litany of woes, to put it mildly. States which are supposed to provide us comforts of life, to ensure our protection, have evolved only to become sophisticated prison houses, where the illegally wealthy few rule the roost, and the majority, reduced to a cleverly duplicitous form of slavery, work all their life to feed the filthy rich. Has it always been like this?

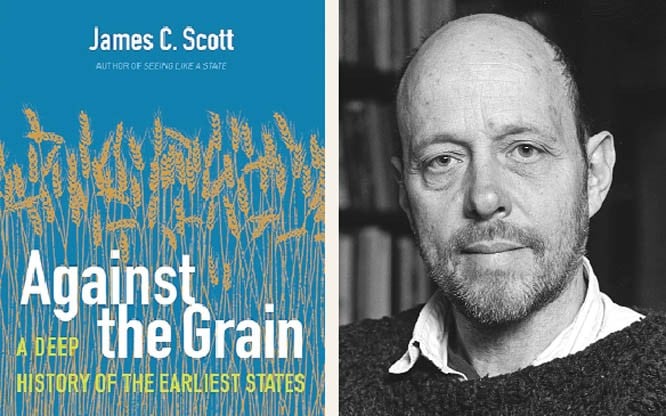

In a ground-breaking book entitled Against the Grain (note the double meaning) James C. Scott, a professor of political science at Yale University, who, with mock modesty, calls himself an amateur, has upended many fanciful definitions of early states. He mainly concentrates on ancient Mesopotamia because of the richness of the evidence. The period covered is from 4000 BC to 200 BC.

We like to see in history an orderly, linear progression, during which the early homo sapiens are seen as primitive people, nomadic, surviving as hunters-gatherers, living in fear and abject poverty, at the mercy of natural forces they didn’t understand. However humanity forged ahead, albeit slowly, cities sprang up, states emerged, usually dependent on fixed-field crops, the prehistoric and preliterate ages came to an end. It was the beginning of civilisation, ushering in civil peace, social order, formal religion, freedom from fear, setting in motion culture, making historical records, law codes and literary activities possible. It is a convenient and comfortable picture.

In his book James C. Scott has torn up this picture. He shows, convincingly, that coercion was the main factor in establishing and maintaining the ancient states. On the other hand, those populations, regarded as barbarians or primitive, remained outside state centres for millennia may have chosen to do so because their way of life was better and less encumbered.

What about fire, for instance. The discovery of fire owes nothing to the beginning of statehood. Evidence of human fires is at least 400,000 years old. Our ancestors knew how natural wildfires changed the landscape. Old vegetation was burnt away, to be replaced by quick-colonising grasses and shrubs, bearing berries, fruits and nuts. They also used fire to drive herd animals off precipices. Once they learnt how to make fire they also turned, as the occasion demanded, into slash and burn cultivators. Fire also allowed food to be cooked, making it more digestible. Later on, fire also allowed many new professions to flourish, that is, pottery, the blacksmith’s art, baking, metalworking, brewing - not necessarily the doing of townsmen.

It is also incorrect to assume that the states invented irrigation or crop domestication. These were the achievements of prestate people. Even today, Scott says, there are large stands of wild wheat in Anatolia from which, as has been proved, one can gather enough wheat with a flint sickle in three weeks to feed a family for a year.

What about the early states. They were an innovation and very fragile. Proper governance is an art and a difficult one at that. We are, globally speaking, still no good at it. The early states rose and fell constantly, wrecked by epidemics or famines, civil wars or insurgencies, or attacks by rival states or barbarians. Sometimes the invaders resorted to scorched earth tactics, setting crops on fire. Occasionally they behaved intelligently, waiting for the harvest to be reaped and stored. An attack immediately afterwards yielded rich dividends. Looting the entire harvest must have been great fun for the raiders. In either case, the victims had nothing to look forward to save famine.

How big were these cities, the hubs of the states? Guesstimates suggest their population to be anywhere from five thousand to ten thousand. By 3200 BC, Uruk was almost certainly the biggest city in the world, with anywhere from 25,000 to 50,000 inhabitants, together with their livestock and crops. The cities were walled, the walls a sure give away that something valuable was being protected. No wonder that Gilgamesh, a founding king, is said to have erected the city walls to safeguard his people.

It is striking that virtually all classical states were based on grain. Scott’s guess is that only grains are best suited to concentrated production, tax assessment, appropriation, cadastral surveys, storage, rationing and transportation by land or rivers or sea. However, ploughing, planting, weeding, reaping, threshing and grinding called for hard work. For the state to function effectively a large number of unfree labour was needed. Prisoners of war, convicts and communal slaves filled the bill. Slaves were also needed for building city walls and roads, digging canals, mining, quarrying, logging and monumental constructions. The life of the slaves was one of unrelieved, wearisome drudgery. Nonstate persons must have felt that to live in the wilderness without masters was vastly preferable to working like a dog in the walled cities.

Not only were the cities overcrowded and squalid they also attracted a lot of unwholesome creatures like mice, weevils, ticks, bedbugs, cockroaches and lice. Dogs and cats also joined in. This uneasy mix helped proliferate diseases like measles, mumps, diphtheria, flu, TB, smallpox, typhus and bubonic plague. In addition, there were class differences, the royalty and the rich making merry all the time, the poor leading a hand-to-mouth existence, the miserable slaves toiling away. The very image of a society on the verge of bedlam and explosion.

You might say: well, that may be true, the non-state population, the so-called barbarians, being better off, roaming freely around, but didn’t the city-states improvise writing and by doing so made religious texts, literature and history possible? Wrong again! States, based on large-scale grain production, emerged between 3300 and 2350 BC. It is roughly at this time that writing made its first appearance. Every state, even an early one, needs a system of numerical recordkeeping. Writing was basically used for bookkeeping purposes for more than five hundred years. Neither in China nor in Mesopotamia was writing originally devised as a means of representing speech. The earliest administrative tablets from Uruk are lists on lists, of grain, manpower and taxes.

The modern world is Uruk updated and multiplied by a million. As they say, the more it changes the more it remains the same.