Instep Overview

The business of fashion has many cogwheels that keep it turning and can aid in its growth. Trade expansion, a solid international presence, the introduction of new designers and the evolution of older ones, standards of professionalism in the industry, growth of the high street and memorable campaigns are all factors that help the industry progress. While we have managed to rectify quite a few issues, there are some that still linger, dragging down overall industry standards.

Here’s an overview of Pakistan’s fashion growth in 2018, or the lack thereof…

International forays

Several designers showed abroad in 2018. Sania Maskatiya, with Sania Studio, showed her S/S ’19 collection at New York Fashion Week, Shamsha Hashwani showed her S/S’19 collection at Vancouver Fashion Week, Zuria Dor showed at Jakarta Fashion Week and eclectic jewelry designer Zohra Rahman took her S/S ’19 collection to Paris Fashion Week. HSY, more recently, collaborated with Scottish brand Harris Tweed for an innovative collection. While numerous designers have shown at international events through the years, some pulling the right connections and others going by virtue of merit, fashion is always a good way to market brand Pakistan to the world.

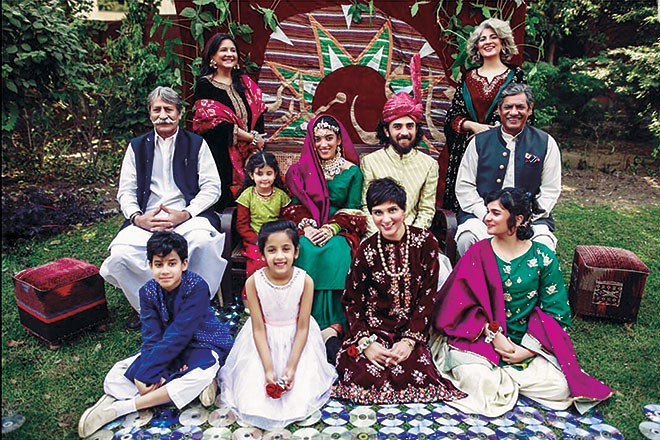

Therefore when Lahore based designer, Mohsin Naveed Ranjha got Ranveer Singh to model his clothes on the cover of big-time Bollywood magazine Filmfare, it was a coup and a half. While he may have paid a hefty fee to get that coveted placement, he allocated his budgets towards intelligent marketing. The cover put the designer on everyone’s radar at BCW and one could overhear people discussing MNR alongside names like HSY and Nilofar Shahid. That is what one strong campaign will do; the challenge is to follow it up and stay in the limelight.

Another designer who has had good luck with Bollywood celebrities is Saira Rizwan. She bagged Kangana Ranaut earlier in the year, having shot with Shilpa Shetty and Amy Jackson in the past. One wonders whether shoots with celebrities from across the border garner an actual increase in sales. Do they lead to the brand’s retail presence in India? Does it have any impact on their business altogether or is it purely about image making (like in MNR’s case)?

While we’re on the topic of image making, this year Nabila was the official stylist for India’s acclaimed International Indian Film Awards (IFFA’s) and then again the stylist for Indian designer Manish Malhotra’s show in Qatar. She has swiftly positioned her brand in markets abroad, selling the No Makeup palette internationally and working with international stars like Lindsay Lohan and Manish Malhotra. Nabila and her team definitely broke new ground in 2018.

On the flipside, one didn’t see much retail activity for local brands internationally. Khaadi opened a flagship store in Glasgow, taking their count to round about 60 stores globally, including Pakistan. Faraz Manan continued growing through the UAE, consistently reaching out to a high-end clientele traversing the Middle East and India. But that’s more or less it. Designers showing all over the world obviously did not translate to designers taking their businesses to the world. We’re not counting exhibitions and trunk shows as veritable growth.

The highstreet

There is no iota of doubt that the high street continues to grow in Pakistan. A multitude of ready to wear brands are expanding and driving out designer stores from malls, where the high street truly is thriving. Two major high street brands on the market this year were Zaha and Afsaneh, both helmed by Khadija Shah. While Zaha was launched as her eponymous high street brand, Afsaneh was created under the umbrella of the Hussain Group, with Khadija as Creative Director.

Khadija’s association with Sapphire put the textile brand on the high street map but both Zaha and Afsaneh are yet to establish a brand identity strong enough for one to be able to identify their outfits in a sea of similar looking flora and fauna designs. Khaadi’s Chapter 2, however, created dominant characteristics and a strong signature - both signifiers of a memorable brand that is here to stay.

Another consistent low observed throughout the year was the weak supply chain. Videos of sales, where women break through the doors, scream, shout and manhandle salesmen, are old news. This hysteria does not happen because a brand is so covetable rather because false marketing is implemented. Claiming that your product is sold out the moment it goes online also does not indicate that your brand is doing extremely well. It just means that a) the supply is not catering to the demand, indicating a weak business model, and b) most designers sell their collections to retailers like Saleem Fabrics and Portia in advance and then put a ‘sold-out’ sticker online, misleading the customer into thinking an item is sold out while it may be available in the market place for weeks on end. One observed many popular high street brands advertise pre-booking online, claiming to be sold out before the given time for the sale.

While we’re talking about industry lows, a word on standardized sizing, which still remains an issue even though the Pakistani masses now have a plethora of high street brands and price ranges to choose from. Khaadi’s medium will be an entirely different size from a medium at Sapphire and pants it seems are made entirely on whim, with varying waists and lengths. Sizing is one of the easily resolved aspects of production but standardization it seems is nowhere on the horizon of ready to wear businesses. For the average sized Pakistani woman, it’s a demoralizing experience to go shopping at local high street brands. Designers envision their designs on thin women so when women of different body types wear the same clothes, especially pastels and large scale lawn prints, they create an unflattering look. The high street urgently needs to cater to the average woman and design for all body types.

No prominent entrant

There is a large number of fashion students graduating every year from the many fashion schools dotted around the country – Lahore’s Pakistan Institute of Fashion Design (PIFD), Beaconhouse National University (BNU), National College of Arts (NCA) and the Asian Institute of Fashion Design (AIFD) in Karachi. But still, the number of breakthrough designers is just a handful. Hussain Rehar, Hira Ali, Hamza Bokhari come to mind but the rest of the graduates seem to have been nabbed up by the growing high street. It seems to be harder and more expensive to set up a brand than it ever was before. Looking into marketing costs, PR, production, retail space, fashion week costs can be daunting for a fresh grad so most of them settle into well cushioned jobs as designers for other brands. Technically there’s nothing wrong with that; not every graduate will be an independent designer and working with design houses is an integral part of experience and growth. But eventually one needs to see the industry grow in every direction. Since the prices for all imports have gone up by almost 30 per cent, it has generally become even harder to sustain a business let alone establish a new one. Humza Zafar, CEO at Hira Ali shares, "for a fashion grad; funding available, social clout and of course, good design sensibilities decide their future." Therefore we see many talented young designers starting out bravely but withdrawing all too often, due to lack of investment and business opportunity.

What happens with young designers who take jobs in the high street is that they at times curb their creativity and adapt their design sensibilities to the high street masses. To ensure that the new breed of designers keeps coming forward, fashion councils should not only mentor but also arrange for financial investments, subsidized retail spaces and slash fashion week participation fees’ for new comers.

Models

A handful of good models came forward this year. Yasmeen Hashmi, Rabia Chaudhry, Eman Suleman, Mushk Kaleem, Fehmeen Ansari and Roshanay among others stood out. Older ones like Anam Malik were recognized for their talent with a long time coming Model of the Year award. Ironically, while one may have thought it was a good year for models, Anam took to social media to allege that she and fellow model Farwa Kazmi had not been paid for a fashion shoot they recently did, along with sharing perturbing stories about the (lack of) standards of professionalism in the industry. Local fashion has long passed its fledgling phase, there are big mills, ateliers, high street stores running so proper representation for models should be part of the growth. Currently, almost none of the models have agencies or managers behind them, which means that in any situation it’s their word against the client’s, leaving them in a weaker position.

There are older models like Vaneeza Ahmed, who’s seen choreographing major shows and Mehreen Syed, who mentors models at her academy but there needs to be more support. There needs to be unity amongst the models because it’s easy for another model to pick up a project that’s been dropped by one because of unprofessional behavior. There needs to be a collective union of creatives in the industry where they can stand behind each other and fight for better work practices. There is power in numbers. Additionally, there is still very little diversity amongst the models we see on billboards, ramps and our social media. We’d like to see transgender models, plus size models, models with skin conditions, hijabi models and older models become more common.

Campaigns

Inclusivity in local campaigns, though on a rise in 2018, is the exception not the norm - it is still seen as a buzzword and a PR push. Pakistan has the occasional brand use ‘real women’ for their campaigns but it is being done on a very small scale. Generation has been monumental in their advertising because they’ve been consistent with their messaging and may actually be able to alter certain perceptions. Repetition is key; when we see something over and over again we normalize it. Such campaigns create familiarity, which in turn breed acceptance and tolerance. That’s why it’s important to see a range of body shapes in images and on the ramp. Here’s to hoping that next years’ fashion week pool will have more diversity.

Solo shows

Last year the the solo show trend came back with every designer who could afford it, breaking off from the fashion week bus and orchestrating a solo outing. 2018 had two main solo shows with HSY’s extravagant Mohabatnama in Lahore and Shehla Chatoor’s show in Karachi. Fahad Hussayn experimented with a different format, recording an entire runway show and then airing it digitally on his social media. Faraz Manan, who was the first to break off from PFDC to show independently years ago, marked a return to the platform. It is evident that designers are showcasing as and how it makes sense for their brand rather than following any ‘trends’.

In 2019, we not only hope that Pakistani fashion traverses further abroad but that trade connections become stronger. We’d like to see designers show in new and exciting ways, creating experiences and a distinct, original aesthetic rather than merely putting together a show of commercially safe clothing. We’d like to see the high street get more interesting rather than follow the mass-friendly generic route and create brands that stand out from the clutter. Industry practices and treatment of creatives should become better this year. There should be standardization of not only sizes, but of practices all around. There should be support for one another and for the new generation of fashion. How else will we see any growth?