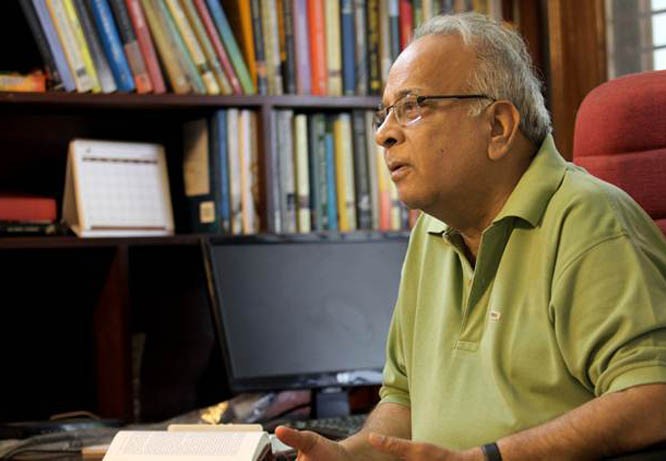

Mushirul Hasan (1949-2018) has left a legacy of amazing historical sensibility and responsibility which will guide and inspire generations of future historians in South Asia

He had to carry the legacy of the divided nation as he was born in India almost two years after Partition when the ‘Muslims were generally viewed as a religious collectivity who (we)re presumed to represent a separate political entity’, if not the sole conspirators who had partitioned the nation. In his ground-breaking work on Indian Muslims, Legacy of a Divided Nation: India’s Muslims since Independence (1997), Prof. Mushirul Hasan, who passed away recently, had raised a series of questions that perhaps rescued the Indian Muslims from becoming mere stereotypes.

Being one of the most prolific historians who could analyse a huge amount of records within and beyond archives that reflected his authority on the contemporary literary references, Hasan had always challenged the hegemonic version of history, replacing it with plurality of perspectives which could help reveal the complex layers of the composite political culture of pre- and post-Partitioned India.

Born in a family of historians, Mushirul Hasan followed his father Mohibbul Hasan, when he chose to study History. Trained in Aligarh, Delhi and Cambridge, he joined teaching in Delhi’s Ramjas College. Later he was selected as a Faculty in Jamia Millia Islamia where he served for more than thirty-five years, initially as a teaching faculty but later in his career, as an administrator, in the post of Pro-Vice Chancellor and also as the Vice-Chancellor.

Writing about his contribution, Prof. Hari Vasudevan, professor of History, Calcutta University, mentioned him as one of the finest of his generation. Hasan’s abiding interests in unveiling the complexities of the socio-cultural fabric of modern history had perhaps led him to explore a wide variety of subjects, spanning from the history of communalism (1979) and the rise of political Islam in northern India to the idea of pan-Islamism (1981) that included the terrains as far as the Indian Ocean and Ottoman Empire. But Islam or Muslims, particularly in the Indian context, always remained far from being monolithic to him.

Hasan had always attempted to understand the nuances of the Indian Muslim identity/identities by exploring the life and time of a number of individuals which led him to write political biographies of personalities like Mohammad Ali (1995) and M. A. Ansari (1987). Being a complete historian, Hasan’s minute observation did not miss out the socio-political contexts of these individuals which further took shape in his researches on qasbas of colonial Awadh (2004). His junior colleague and one of the prominent contributors of the subaltern studies, Shahid Amin has estimated this work as a specimen of his poetic craftsmanship where the socio-political components such as the world of the patriarchal landlords, their subordinate artisans and the fun and frolic of the cash-rich economy was weaved in with ultimate mastery.

Hasan’s passion for exploring political culture led him to focus on popular media which bore fruits in his two excellent historical researches -- one on the humour of the Awadh Punch (2007), and the other on the contemporary portrayals of the Muslims in media in Moderate or Militant: Images of Indian Muslims (2008). He never hesitated to look into alternative sources to enhance the quality of historical researches which was spelt out in the volume on the Partition (1993) where he introduced the trauma by placing the literary work of Saadat Hasan Manto’s Toba Tek Singh as the opening chapter of the collection.

With his the variety and quality, Mushirul Hasan had become one of the most prolific historians who had more than twenty monographs to his credit.

Apart from being one of the finest historians of his generation, Hasan was a brilliant institution builder who perhaps revamped the century-old institution of Jamia Millia where he introduced a series of new departments and institutes, such as the Centre for Dalit Studies, Academy of the Third World Studies and Centre for Peace Studies. He was also credited for pulling in huge funds for building enterprises which helped to build a world-class library that brought back Jamia Millia to the academic mainstream. He was thus often fondly remembered as the Shah-Jahan of Jamia, as mentioned by Mohammad Shakir, his assistant for last twenty years.

He, however, had to face resentments, especially from the conservative quarters for transforming the image of the institution. His open support to Rushdie’s Satanic Verses earned him many enemies which almost put him out of the campus during his tenure as the Pro-Vice Chancellor of the institution in the 1990s. After his retirement from Jamia, he also served as the Director of the National Archives of India.

Also read: A historian par excellence

Despite being an administrator of public sector institutions, Hasan was always cautious about state-intervention in history-writing endeavours. In Making Sense of History: Society, Culture and Politics (2003), Hasan argued in favour of maintaining the ‘historian’s sacred autonomy’. Perhaps this challenge to the historian/intellectual’s role is what compelled Hasan to share his views with the world beyond academics via fortnightly columns in newspapers and public media where he constantly addressed issues from the past as well as of contemporary world during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

His accident in 2014, however, put away this brilliant historian and institution builder from the public life. Hasan was battling ill-health since then. Mushirul Hasan passed away in the early hours of December 10, living a legacy of amazing historical sensibility and responsibility which will guide and inspire generations of future historians in South Asia.