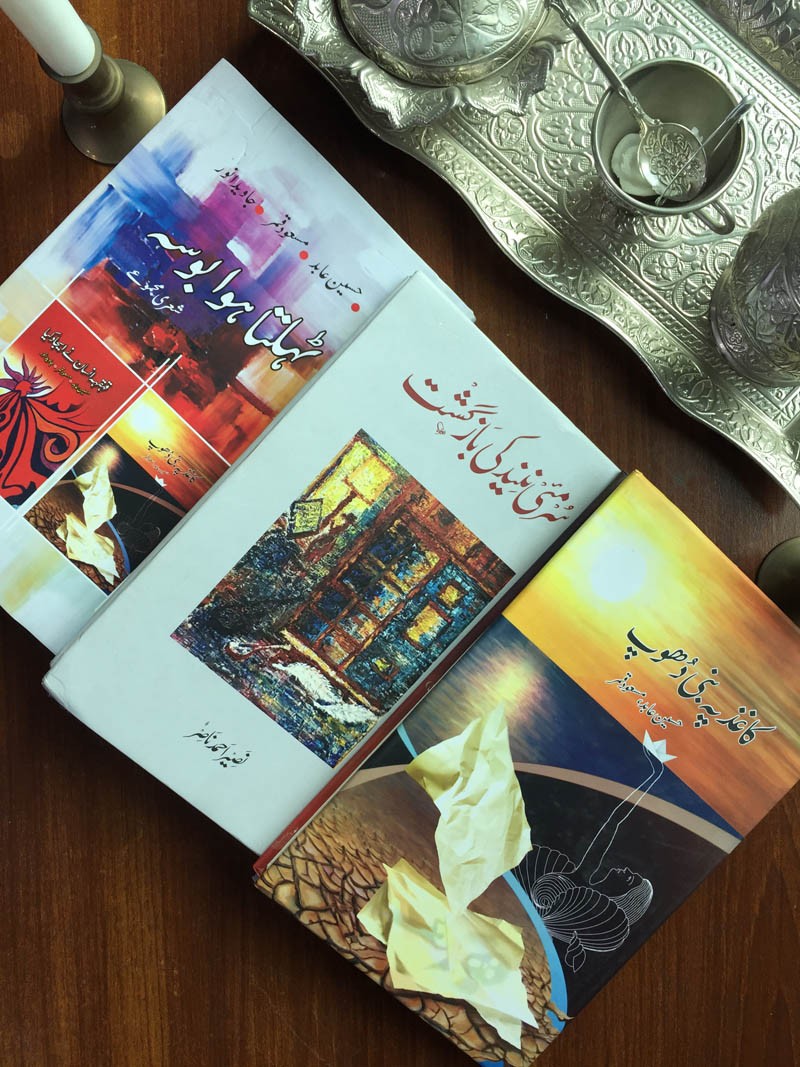

How else will more readers be drawn towards Urdu books before reading them -- except by how they look?

It happens almost instantaneously. Without us even realising what’s happening, without any warning. No matter what we are told about refraining from judging a book’s content by its cover, we can’t avoid it. The more alluring, the better. However, as far as publication of Urdu books in Pakistan is concerned, one can’t help but think that these books are selling despite the covers, not because of them.

Some research that was done years ago into book buyers’ purchasing habits showed that most people in bookshops will decide to buy a book approximately in between 10 and 20 seconds. Based on this study, it is the book jacket, apart from the title and blurb, that should display a strong, memorable image.

However, the publishing industry in Pakistan seems to conveniently overlook this little detail while publishing books in Urdu.

"Publishers these days are hesitant to invest in the design of jackets," art critic Quddus Mirza says. "They typically have in-house designers who take care of all the illustrations that go with the books."

Mirza says that in the years gone by, publishers would employ artists to produce book cover images; which would naturally be more appealing than the dreary covers that are being churned out these days. "Zulfiqar Ahmed Tabish, Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Jamil Naqsh, Sadequain, to name but a few, were among the artists who were actively involved in the designing of book covers." He believes Urdu publishers are not even aware of the significance of a good cover, mainly due to a general lack of exposure.

Noted Urdu critic and fiction writer Nasir Abbas Nayyar concurs: "Most publishers that I’ve come across are completely illiterate and hence unaware of what the Urdu reader really wants. This is worrying, considering that it is books we’re talking about." He says for most publishers, the writer’s name and to some extent the content of the book are the only aspects that matter.

Fortunately, however, there are a few publishers who take the cover business seriously. "Covers are absolutely important if the publisher wants an increase in the sales of books," says Khawaja Aslam, who works at Readings, one of the major bookstores and publishers in Lahore. "We have hired specialised designers to try and bring the quality of our books equal to the international market standards."

Abubakar Siddique who works at Maktaba e Daniyal, a Karachi-based Urdu publisher, begs to differ: "We don’t need attractive titles to sell books, as it is content that really matters. If the content is good people will buy it, regardless of the cover. Attractive covers are designed to lure non-readers; regular readers don’t depend on these things to choose books." One wonders if the publishers shouldn’t probably turn their attention to non-readers too.

According to Nayyar, these issues aggravate due to the absence of editors in publishing houses -- to act as a bridge between authors and publishers. "A competent editor in the publishing process is crucial; preferably someone who understands art and what the reader really wants, and can guide the publisher accordingly."

Also, the fact that the author and to some extent even the designer are hardly ever consulted by the publisher while choosing a cover design, doesn’t help either. "When I used to design covers, the publisher once asked me to avoid using the colour black as it would ‘decrease’ the saleability of books," says Mirza.

The problems with Urdu books unfortunately do not end with the title. There are two other things that impact the reader’s final decision to actually buy a book: price and paper quality. Though some would argue the two are directly proportional to each other, Aslam thinks otherwise: "Publishers all over the country are more or less using the same kind of paper which is being imported." He says the paper quality is usually substandard, but publishers have to make do with whatever they are getting. "There is hardly any difference in the production quality of books, barring a few; mainly the cover design." According to him these differences do not warrant the kind of price increases that we are witnessing in the book market presently. "Huge difference between the cost and price of books, unfortunately, points towards an underlying ethical rather than an economic problem."

So how can the production quality of books be improved? "It all comes down to the kind of investment the publisher is ready to make," says Nayyar. "However, most publishers are selling books to local libraries in bulk, which means quick returns on their current investments. After which they generally feel no need for any further investment."

Broadcaster and linguist Arif Waqar couldn’t agree more. "If a book is worth Rs400, the publisher would put Rs1000 as the price tag. The extra 600 rupees would then be divided between the librarian, who has approved the purchase, and the publisher. The show-room sale is a very minor part of the publisher’s business; his main income comes from libraries."

Waqar suggests some other measures in order to increase the readership and sales of Urdu books. "In Pakistan, at least five different government/semi-government publishing organisations that are currently consuming public funds in the name of Urdu can all be merged into one central organisation. In the private sector, we need something on the lines of English Book Society that used to publish cheap paperback editions of expensive books."

Book critic Moazzam Sheikh expresses the need to cultivate a culture for propagation of any language, let alone Urdu. "The writer has to modernise the language constantly by striking a delicate balance between the emerging street language and a people’s linguistic heritage or inheritance." Nayyar maintains that writers have to be extra assertive about their rights to be involved in the production process of books. "If they themselves are going to forgo these rights, what can anyone else do? Besides, Urdu books have to be advertised in a better manner. Some bookstores are now actively trying to advertise Urdu books by using social media, which is a refreshing change."

As I loitered in a local bookstore last Sunday, I observed an old woman with a couple of Urdu books in her hands, wandering down the aisle. The covers were kind of tacky but she seemed thankful anyway. "Ah! But I wouldn’t mind a good looking book. After all, a thing of beauty is a joy forever," she smiled.

Perhaps it’s time the publishers paid heed as well.