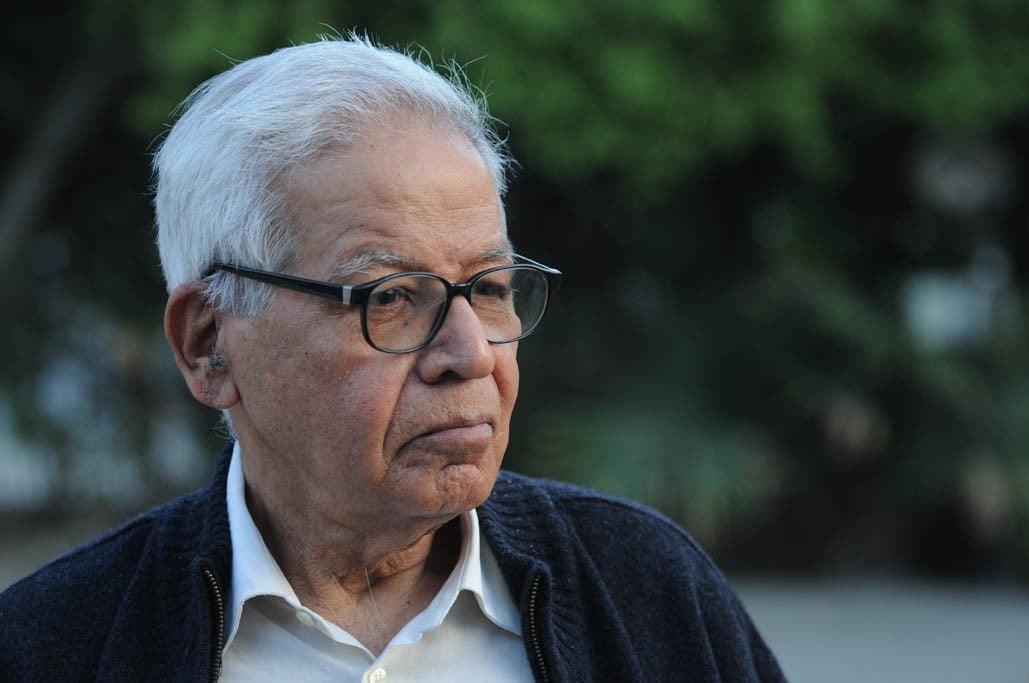

A fighter for economic, social, political and human rights, this is him. If it is right, he fights, even if he is alone

The scene: Office of the Principal, Shah Husain College, Lawrence Road, Lahore. The office was usually occupied by Professor Eric Cyprian, as the Principal himself, the charming Professor Manzoor Ahmed, was generally out seeking support for this new venture started by teachers dismissed from Islamia College, Civil Lines for courage of conviction. Amin Mughal, the third academic in this troika, was also present, talking to the students who followed him from a just concluded lecture. And there was me, a new recruit to teach the dismal science of economics.

It is the beginning of the winter of 1970, the run up to the most tumultuous elections in our history. Enters a gentleman in a casual attire, lowers himself in a one-armed chair with great ease, and loses no time in taking on everyone in the room in his Urduised Punjabi on issues ranging from personal to political. This is when I first saw Husain Naqi. He had just become the regional head of a new daily from Karachi, The Sun. He was there to gather a regular team of writers. He asked Saab, as Professor Cyprian was known among friends, to become a contributor.

Now Saab was a teacher in the oral tradition. He could spellbind an audience for hours on any issue, but had no patience to pen his thoughts down. Looking at me, he said to Husain Naqi, "Why don’t you ask him to write for you." Saab knew I occasionally contributed to The Pakistan Times. As I found out later, Husain Naqi was great at encouraging young entrants into the business of writing. Almost every other youngster admitted to being his shagird. A bit disappointed at Saab’s response, he did ask me to send him some piece.

In its layout and printing style, The Sun was perhaps the most modern paper during its short life. Husain Naqi liked my thoughts but not their straying. "Remember, you are not writing for yourself but for the immense variety of newspaper readers," he would say. "Even more important, you are not the only contributor."

The result of this coaching was that I was invited by the paper to join the editorial team in Karachi. I did not join but enjoyed my maiden air flight.

Husain Naqi’s sojourn also ended sooner than expected.

As I knew by now, he had a history of standing his ground, whatever the cost. Hailing from an urbane family of Lucknow, he migrated to Pakistan and quickly assimilated the local cultures and politics. A born activist, he held elected offices in student unions, trade unions and was in the forefront of rights struggles, be it nationalities, women, children. He was jailed, hounded by goons and rendered jobless in short intervals.

However, he was not the one to exit. The voice continued, with sound and fury signifying everything about an undying spirit, and undiminished optimism in the betterment of human condition.

Students spearheaded the movement against the dictatorial regime of Field Marshal Ayub Khan. Husain Naqi, leading the Karachi University Students Union and the National Students Federation, was in the eye of the storm. When some students from Balochistan were expelled from Karachi University, Husain Naqi and colleagues led a protest that resulted not only in their own rustication, but also externment from Karachi.

Husain Naqi returned to Lahore, where he had been the Secretary General of the Students Union, Islamia College, Civil Lines. Back in Lahore, he was Bureau Chief, Pakistan Press International, started an eveninger Punjab Times, contributed to the Holiday, Dhaka, and Outlook, Karachi, all to the displeasure of the powers that be.

After the elections in December 1970, the country was in a state of ferment. The estrangement between the two main political parties, the Awami League and the PPP, the machinations and the manipulations of the dictator General Yahya Khan that eventually led to military operation in East Pakistan and a complete blackout of news -- all created an atmosphere of dismay, despondency and denial. Dissent from official dispensation and pronouncements became subversion of the state. Indeed, it was worse. In the absence of credible information, discussion even among friends dissolved into acrimony.

In this backdrop, Husain Naqi picked up the gauntlet and published Punjab Punch, with its masthead declaring it as a views weekly. All the news in the paper was, unashamedly, views. In the commanding style that he reserved for situations when no was not acceptable as the answer, he asked me to be the editor. I was 23, with not much writing to my credit. I was still waiting for my Masters result for an examination held a year ago, something normal in those days of turbulence. Nevertheless, I had to take the plunge.

He lectured me on dos and don’ts, focusing mostly on my Bohemian style than the business of journalism. As the work on the first issue started, I found out that there was nothing to edit. With a core team consisting of Zafar Iqbal Mirza (ZIM), Masudullah Khan and Husain Naqi, and writers like Khalid Hasan, Ashfak Bokhari, Khadija Gauhar and no conventional editorials, the editor could only contribute his own piece. Most remarkably, Husain Naqi was finally able to bring Professor Eric Cyprian to the world of writing regularly. Najm Husain Syed was brought in to unveil the recurrent patterns in the Punjabi literature.

Punjab Punch was a newspaper without an office. It was printed at the Packall Printers owned by Muzaffar Qadir, stretching his, and Khadija Gauhar’s generosity. In this very office, The Code of Civil Procedure: Act V of 1908: Commentary by Aamer Raza A. Khan was first edited and printed. Once the agencies came looking for the office, only to be directed to a bench in the basement of Packall Printers that was used by us during the printing. On another occasion, the entire paper disappeared from the market soon after its distribution in the morning.

The experienced Husain Naqi had guessed it right and made the alternate arrangements. Madeeha and Faryal Gauhar used to hawk it outside Kinnaird College. Only Husain Naqi could run the whole affair on a shoestring budget. He alone could get the message across to the unsuspecting folks in the then West Pakistan that the denial of the democratic rights of East Pakistan was destroying the state of Pakistan.

During an address at the Punjab University, only he could tell Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in his face what wrong had been done. Years later, he did write to me to say why he chose me as the editor. He wrote: "I was concerned to appoint an economist as editor because of the serious economic underpinnings of the major political issues facing the nation in those days -- the economic disparities and worsening income distribution being the most important."

This was, and is, Husain Naqi, a fighter for the economic, social, political and human rights. If it is right, he fights, even if he is alone. No wonder, some friends address him as Imam Hussain. Another December is approaching. Heeding Husain Naqi and some others in 1971 would not have made us wish Decembers away.

Poochchte hain woh k Ghalib kaun hai

Koee batlaao k ham batlaayain kya