Gliding through the 18th century India with Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

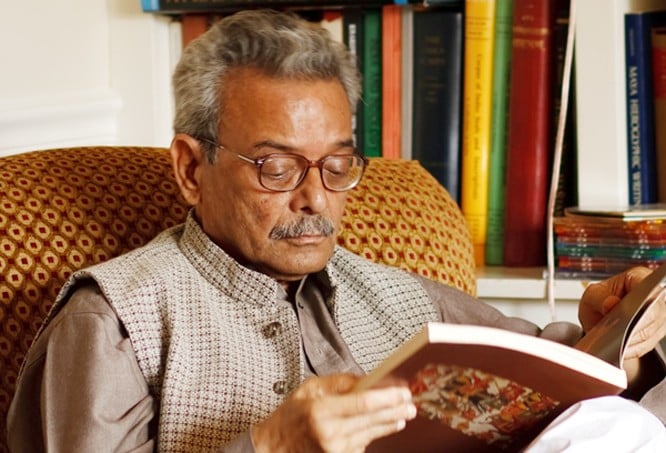

I don’t want to call Shamsur Rahman Faruqi a workaholic. The noun carries a whiff of disparagement and will not be appropriate at all. This aside, as soon as you look at how much he has written and translated, a great deal of it qualitatively dexterous, you are left speechless. How on earth can anyone have the ability or leisure to be so consistently creative. Also, keep in mind that he was a civil servant as well who eventually held some important posts. To reach some kind of eminence in the civil services may add to one’s self-esteem but in general is exceedingly tiresome.

The question, therefore, is how to deal satisfactorily with his prodigious output in the limited space of a daily’s column. It is to attempt the impossible. So I will confine myself to a few comments on his shorter fiction which, every time I reread it, seems inimitable, charged as it is with the strange charm and mystery of a bygone era of our literary and cultural history. He is capable of visualising the quickening, kaleidoscopic vistas of the past like a virtuoso, like a time traveller. His short fiction can be wrongly labelled as historical. It does possess a basis of facts to underpin the depiction of events and personalities. However, the overall impression is one of imaginative recreation.

Let me dispense immediately with ‘Lahore ka aik waqia’, the only weak link in the collection. Faruqi says that he saw in a dream the incidents narrated in the story. It may well be to a large extent true. The narrative is pervaded by a senseless terror which we are wont to experience in some of our dreams. But dreams are often like uncut jewels. More attention was needed to add to or subtract from the dream’s amorphousness.

Three of the stories are centred around Mirza Ghalib, Meer Taqi Meer and Mushafi’s wife. The fourth has the mid-eighteenth century Delhi as its background. Some of the characters in it are real but the two persons around whom the story revolves are, as far as I know, imaginary. I may be mistaken though. Faruqi has such a firm grip on facts and details that it is difficult to sift reality from fiction.

Placed side by side with the other stories, the one which gives an account of Mirza Ghalib seems less forceful. We get a fair idea of Ghalib’s likes and dislikes, his courteousness and generosity. We learn about his foibles too. He egotistically assumed that all those who belonged to the Indian subcontinent and wrote verse in Persian were incapable of doing justice to the language they used. He alone was the authentic Persian poet. No one doubts Ghalib’s excellence but his vilification of other Persian poets is now seen as mere snobbishness. The tiffs between Ghalib and the narrator, for whom Ghalib is an iconic figure, are enjoyable. The verisimilitude is impressive.

The tragic love affair of Meer Taqi Meer with Noor-us-Saadat, popularly known as Noor Bai, has been recounted with touching vivacity and veracity. She was a very accomplished teenaged courtesan who, accompanied by her equally talented mother, had moved from Isfahan to Delhi during the 18th century. Noor Bai is a real person. Whether Meer fell in love with her or someone else is quite uncertain. In fiction, many things can be made to look plausible. Meer did go out of his mind for a while (he says so in his autobiography), maybe because of an unrequited love. The story is told with great gusto and to good effect. The atmosphere of an age we are already out of touch with has been recaptured with startling deftness. The nocturnal scene during which Meer and Noor are together at last, and for the last time, is evocative of a delicate sensuousness, without any parallel in Urdu literature.

In the third story the scene shifts to Lucknow. It is still the early 18th century. The narration is fluent enough but the tellers are different which results in some complexity. The male narrator’s father, no longer alive, was a devoted pupil of Mushafi who also has passed away. The son, a rich merchant, sets out to seek Mushafi’s widow who, he presumes, rightly as it turns out, may be living in straitened circumstances. He finds her and calls on her now and then. She tells him at length about the life she spent with Mushafi. A third voice intrudes when she recalls some incidents told by Mushafi himself. This medley of voices demands technical dexterity. Luckily, Faruqi is not found wanting. It is a sympathetic view of an essentially lovely woman. Her journey, from what looked like promiscuous domesticity to an insecure existence, in which small bits of comfort are like appeasements out of nowhere, possesses an anguished gravity.

The last story, possibly the most striking, is enigmatic to the extreme. Perhaps its charm abides in the impenetrability embedded in it. Other stories in the collection reach acceptable endings. Not this one, entitled ‘Sawar’ (The Rider).

The main characters are a teacher and a rich merchant who has a penchant for poetry. They form a close friendship. The story, however, takes off when a rumour goes round Delhi (we are back in the 18th century) that a mysterious rider will pass through the city. On the appointed day he appears and disappears. No one is sure of his identity. Who or what this apparition represents, death, affliction, the passage of time? Was it a symbol of things ephemeral? The teacher feels, for no overt reason, that a great opportunity had come his way and he has missed it.

The friendship of the teacher and the merchant ends abruptly. The merchant who was deeply in love with someone, a passion which was not requited, decides to become a faqeer, throws his mansion open, telling the people to take away whatever they like. Soon afterwards he quits the city. He had crossed over, so to say, from profane love to a state of utter abandonment, transcending the temporal.

Meanwhile, the teacher also falls fleetingly in love, sees no hope of success and reverts to his mundane life. He also feels that he has known someone who was truly great and has been witness to a profound mystery. In the end, it is courage that counts.

Why this fascination with the 18th century India, one may well wonder. In his brief introduction Faruqi says that contrary to the received wisdom, which focuses ad nauseam on political decline and ensuing chaos, the 18th century was fecund with live turbulence. The old adamant order had crumbled and from the criss-cross of crevices fresh ideas were sprouting up. The British rule put a damper on everything. Only one question remains to be asked: why didn’t Faruqi write fiction about the here and now? He could have done a better job than most of us.

"Sawar aur doosray afsany" has been published by Aaj ki Kitaben, Karachi