Nazia Ejaz produces a powerful physical presence through expansive spatial effects and evocative colours, in her recent show at Tanzara Gallery, Islamabad

Seemingly simple on first viewing, Nazia Ejaz’s suite of mixed media paintings at Tanzara Gallery in Islamabad, are at once richly complicated and unexpectedly diverse. Ejaz aspires to breadth and nobility in her works, infusing them with deep meaning while calling the show It’s About Nothing II, and producing a powerful physical presence through expansive spatial effects and evocative colour. While pursuing her personal quest, she manages to challenge, and profoundly change, the parameters of painting.

Ejaz continually adds layers to already layered surfaces, constructing what might best be understood as a process-based narrative but could also be described as an intuitive interplay among brushstrokes, forms, and colours. By using the timeline as a conceptual arena, Ejaz in many ways leaps into the subject of the cinematic. Specifically, this structure creates a break in her practice and allows for an introspective approach and a new conceptual viewing of her work by way of an implicit narrative that reveals not only the process of the works’ making but also the importance of their titles, which serve to evoke individual parts of an assumed gravitas as exemplified by ‘Once Upon A Story’. As in experimental cinema, however, the conventional idea of the structure of storytelling is avoided and put under question here, allowing for fragments of the timeline to loosen from their base and to mix and merge as freely as the colours, layers, shapes, and forms in the paintings.

The ancient Greeks would often refer to time either as kronos or kairos. "While the former refers to sequential time, the latter signifies a time in between, a moment when something special occurs." Kairos is what defines Ejaz’s work. She tends to negotiate a metaphysical space -- ethereal and sublime -- with the help of the open nature of compositions and their conventional wisdom, recognised by their capacity for endless exegesis as in ‘In Search Of A City I and II’. These two works, in particular, signal Ejaz’s exploration of the physical, psychological, and ontological realms of darkness and light, which she penetrates with equal curiosity and without fear.

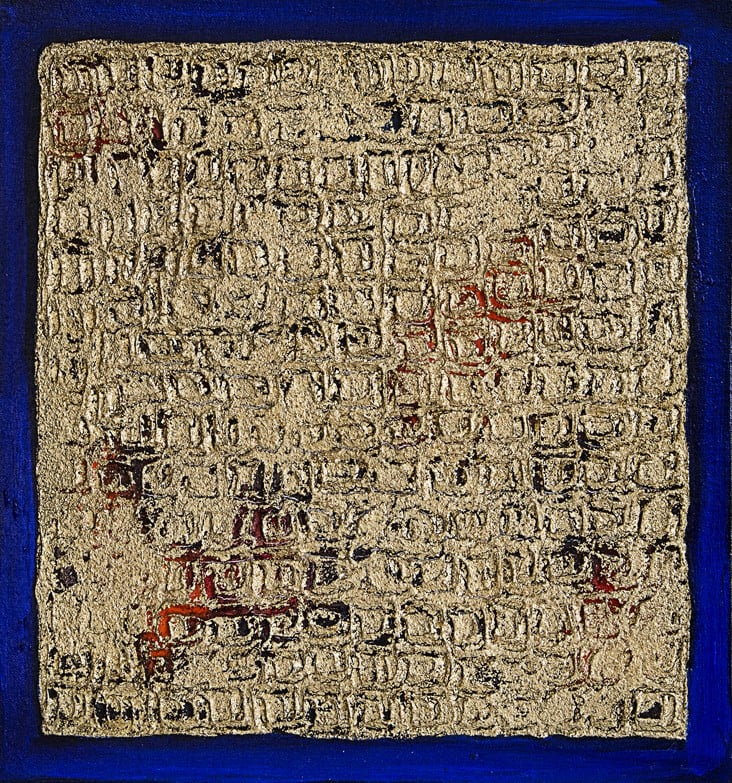

As much as the division within the work suggests a rupture or containment, it also serves to accentuate the solidity of the paintings, as does the layered paint, which, having been poured onto the canvas, reveals the descending trajectory imposed by the force of gravity. The gold, used rather profusely in the paintings, implies a subterranean light that emanates from the depths towards the surface, as in ‘Sacred Ground’ where we find the green and red underpainting that is always at the base of the paintings.

Importantly, Nazia Ejaz doesn’t intend to evoke any feeling or emotion, but rather remains anchored to her process. Her method of applying paint foregrounds chance operations -- relinquishing artistic agency and letting matter express itself. The work’s final appearance depends on a multitude of factors, some such as the weight and density of the material that she employs she is in control of, and others that she does not. Faithful to the teachings of John Cage, she doesn’t fight destiny, but rather circumvents it.

Richly tonal, sensitively nuanced, and atmospheric, the dominant hues in Ejaz’s work -- ultramarine and gold -- relate more to nature. It seems as if the colours themselves radiate light, a flickering light that reveals what lies beyond. Yet Ejaz is not afraid to confront dark spaces, as in ‘Limitless’. In accordance with the principles of Taoism, she shows light and darkness as equal fields, each containing the point of origin of the other, and she reconciles the dichotomy with a wholeness that absorbs everything. All of Ejaz’s paintings are ‘pure’, in Clement Greenberg’s classical sense -- that is, they put a "higher premium on sheer visibility" than "on the tactile and its associations, which include that of weight and impermeability." Certainly, Ejaz’s works are weightless and permeable. Painterly gestures vigorously mark the edges, adding textural muscle. They seem more incidental than insistent, though, nominally suggesting the paintings’ limits by calling attention to the edges of the canvas.

In all, though, the calculated artistic tasks of picturing and constructing are conducted in parallel with demonstrations of painting’s pleasurable materiality. Illusion is set off against the haptic, allusions are set off against structures, and sign systems are juxtaposed with the pure substance of slathered oils.

The paintings on show project a more miasmic, unsettled sense of space and more fluidly unstable internal structures. These paintings are full of melting and merging forms, simple shapes given an orderly appearance: crumbling circles streaked with paint, or roughly sketched, spliced together assortments of spangles. And even if ‘Archive of Longing’ signals a return to verve, the paintings’ jampacked, motley arrangements of elements betray artistic agitation and uncertainty.

The entropic descent towards disorder in Ejaz’s work has reached productive depths of painterly intensity. The recent show displays an altogether new forcefulness and concentration. Several small and midsize paintings in this exhibition are composed with lumpy and uneven rows of clotted gold mixed with sand. The space around is a flattened match for the inner frames -- loosely patterned planes composed of a rich marbled raw material. The crude, toughened paint becomes refined as a beautifully flecked abstract composition. Here, paint seems churned up, then evened out.

Such works appear to prioritise material density over compositional design. An extraordinary compacting of components calls to mind the phenomenon of dynamic range compression in present-day music production. The effects of Ejaz’s painterly compressions are often more delicate -- the flat inner space of ‘Absence of Melody’, for example, has the finely patterned intricacy of polished terrazzo -- but the frequent sense of too much happening all at once, certainly has a contemporary feel. The larger paintings are comparably intense in their kaleidoscopic complexity: busy, warped spaces, with thin bands alternating as an unsteady ground, over which countless strips of zesty colour are frenetically scattered. These are dizzying works, sending our eyes in a dozen directions at once. Stand close, though, and you discover their extreme density, too. They are as hectically distracting as the world we live in, but as substantial as the ground we stand on.