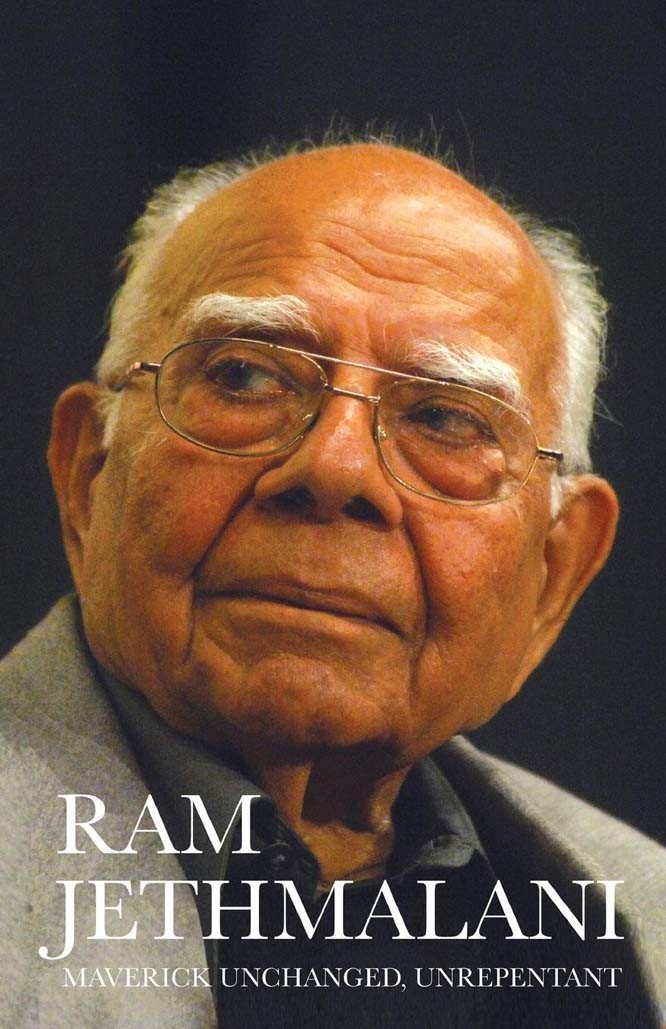

A backward glance at Ram Jethmalani’s autobiography of sorts

Who is Ram Jethmalani (RJ)? A bonafide Pakistani, born in Shikarpur in 1923. We chucked him out. It is a moot point whether making him leave his motherland can be seen as a net gain or loss. Perhaps he is better off where he is, one of the highest paid lawyers in India. We in Pakistan have become increasingly intolerant with the passage of time.

His book Maverick Unchanged, Unrepentant is not an autobiography, although it incorporates incidents from his life. It is more a look at India’s political scene; also what is right or wrong with it in RJ’s opinion.

To begin with, let me quote, in his own words, an early happening in his career which helped change his attitude. He says: I must recall my first appearance in the Chief Court of Sindh before Sir Godfrey Davis and Justice Constantine. I was so full of the facts and law involved in my case that I was going too fast for the judges. The Chief Justice asked: "Are you trying to catch a train?" I said, "No, my Lord." "Are you feeling nervous?" I again said no. And this evoked a surprising response. They replied, "for God’s sake do feel a little nervous."

RJ says that the lesson was learnt, he reformed his style of public speaking, adopting a carefully measured tone and feeling reasonably nervous.

As a maverick many of his views are at odds with generally revered opinions. For instance, he thinks that the uprising in 1857 was not in any way India’s first war of independence. "Out of the vast territory of India," he says, "the area involved in these events was a small part of Indo-Gangetic plain, roughly the land between Lahore and Lucknow. The Sikhs, the Gorkhas and the Rajputs not only did not participate but fully helped the Company’s forces to suppress the rebellion." A counterargument not without weight.

Most of the ire in the book is directed at Nehru whose list of failings and failures are described as long and varied. RJ says that Nehru’s inability to see through Chinese posture of friendship was extremely damaging. Patel, a more intelligent person but not charismatic, warned Nehru, in a letter in November 1950, not to get chummy with the Chinese, an advice Nehru completely ignored. Delusions of grandeur led him to regard himself as the leader of the nonaligned nations. He saw Chou En Lai as his protégé. How Chou En Lai must have laughed up his sleeve at him. The end of the romance in 1962 was galling. Nehru’s illusions were shattered, the Indian army was humiliated in the mini-war and India lost 93,000 square miles in Kashmir to the Chinese.

He thinks that Nehru knew very little about economics or socialism. He was only a self-proclaimed great economist. What Nehru initiated continued to be an obstacle to India’s economic well-being. The miserable rate of growth should have been called the Nehruvian rate of growth. Economic growth revived only after India returned to free market economics. Little love is evinced in the book for Indira Gandhi or Sanjay or Rajiv but Shastri and Modi are lauded. I guess RJ dislikes the idea that democracy should mutate into a dynastic rule -- something absolutely contrary to democratic ethos. Unluckily in Pakistan we have two families which regard the country as their fief or playground.

The most important issue, or scandal, in the book, which RJ pursued as a lawyer, concerns the huge amount of illegal money deposited by Indian citizens in banks abroad. Nothing definite can be said about the total sum but evidently it is enormous. Global Financial Integrity estimated the volume of money illegal owned by Indian nationals in tax havens abroad as being of a magnitude of $500 billion to $1.5 trillion. This was confirmed by R Vaidyanathan, a professor of finance at the Central Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore. The Swiss Bankers Association report of 2006 asserted that Indians top the list of money launderers, with $1.4 trillion deposited in their banks. Apart from Switzerland there are nearly 70 other tax havens in the world.

Take the case of Liechtenstein, a very small country in Europe. Its bank has cash stashed by criminals, money launderers and tax evaders from all over the world. The Germans, by paying an employee of the Liechtenstein Bank, managed to get the names of thousands of German tax evaders. The German finance ministry said that it will reveal, for free, the names of Indian citizens who had an account in the bank.

So far, nothing new. We all know about black money hoarded abroad. What is interesting is the Indian Government’s reaction to all these startling revelations. It did nothing. The Supreme Court asked the government to appoint a Special Investigating Team to recover monies kept illegally in foreign banks. The government refused to comply with the Supreme Court’s order. So much for the supposed power of the judiciary. Why commit harakiri to placate the judges, the ruling elite must have decided. Is anything to be learnt here? Very little perhaps. RJ did learn something, however. "My experience in handling circumstantial evidence has taught me that often false denials prove guilt more convincingly than positive evidence of it."

There are many other interesting things in the book, including a swipe at the unethical behaviour of lawyers in general, funny enough but rather too long to be quoted in full. Here is a wicked slice from it. "The pharmaceutical laboratories in the United States have decided to use lawyers instead of rats in their laboratory experiments. Lawyers are more numerous than rats and there are things which lawyers do that even rats will not." The overall view of politicians, governance, law and order is very gloomy and most of what he says is applicable to Pakistan also.

One of the surprises is a speech he delivered in Ohio before the old boys of Aligarh Muslim University and is surely one of the most cogent and sympathetic defences of Sir Syed’s policies ever written.

All in all, there is an air of despondency here which leaves very little space for cheer. Is this what we looked forward to when we wanted to be free, to wallow more and more around in corruption and lawlessness with each passing year and waste precious resources to purchase arms for wars we are unlikely to fight? One last query. What happens when there is a tug of war between law and illegal wealth? Who wins? Well, illegal wealth will win hands down, laughing all the way.