Interview of Omar Shahid Hamid

I had been trying to talk to Omar Shahid Hamid for quite a while. I had read all of his books. I had also combed through the reviews and interviews online. There were other stories too related to the violence and politics in Karachi. I tried to reach him through the phone but my calls went unanswered. Finally, I had to ask two mutual friends to make him agree to meet me. They put in a word. I rode a train to Karachi after setting up a time with him. I was still apprehensive that the trip might prove futile.

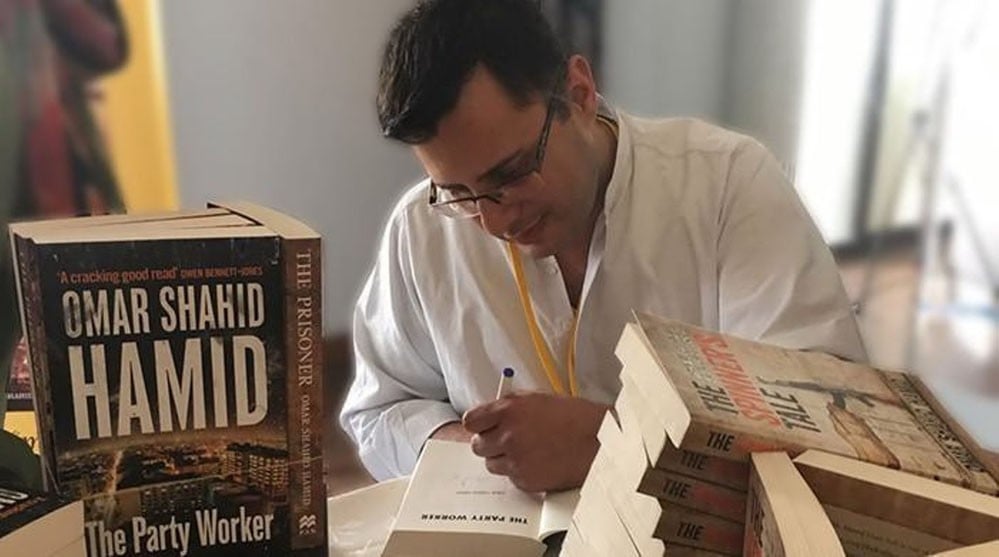

Finally, I was able to meet him one afternoon over a cup of coffee at his home in Karachi. I could feel that he had barely managed to carve out an hour out of his hectic routine. Hamid, a senior police officer and a novelist, has published three books:The Prisoner, The Spinner’s Tale, and The Party Worker. The first thing he told me was that he did not have the luxury of switching off his mobile phone because his job involves fighting crime in Karachi. We discussed the relationship between writing novels and working as a police officer. Throughout the interview, he would elaborate a delicate literary point, attend a call, give instructions on how to conduct a raid on criminals by using unmarked vehicles, and resume the discussion on literature.

Uniformed, self-assured, Omar Shahid Hamid not only discussed the relationship between doing police work and producing literature but also demonstrated his dexterity in dealing with both the worlds. Excerpts of the interview follow:

The News on Sunday (TNS): When did you realise you were going to be a writer?

Omar Shahid Hamid (OSH): I didn’t realise it in that sense. I don’t have that kind of formal training of literature. I am an avid reader of books. But I have read nonfiction more than fiction. Writing just became a means of catharsis at a time when I was feeling frustrated professionally. From there on, it just snowballed into something more serious.

TNS: So you haven’t studied creative writing professionally?

OSH: Not at all. If you talk to my university friends, they will make fun of me and say, "He doesn’t know anything about writing." Prior to becoming a published novelist, I hadn’t even fantasised about becoming a writer. I never had the ambition to become a writer.

TNS: But you are now widely recognised as a writer of books that are compulsively readable.

OSH: Yes. Actually, I am constantly amazed by the response I have got. And it is an interesting phenomenon. Perhaps nobody has tried to write the kind of books I have written. It is genre fiction that is specific to our region. A lot of Pakistani writers have published literary fiction. Moreover, the earlier generation of Pakistani literature in English had become expatriates--for example, Bapsi Sidhwa, Sara Suleri, Zulfikar Ghose etc. Their writings reflected the world they had left behind. They were trying to imagine their home country through their books. Technically, I also started writing while I was living abroad but I had already spent a lot of time in Pakistan. I had gained a great deal of experience as a police officer on active duty. That is something that set me apart. Naturally, I could draw on my professional experiences. What I wrote about would have been difficult to write because you need access to that lived world.

TNS: So you think working for the Police Service of Pakistan has given you some kind of advantage?

OSH: Absolutely. I can say that because my fellow writers often call me up to discuss how to portray a policeman or a criminal or a crime they are writing about. You either have to be a criminal or a policeman to understand the reality of the world I can easily write about. It is not something you can understand by reading books or through hearsay.

TNS: Mohammed Hanif has been in the Air Force of Pakistan and, later, a journalist. So probably he has drawn on those experiences as well.

OSH: Yes. Definitely. Hanif has been a pilot, a reporter, and he is a seasoned journalist. He is also familiar with the underbelly of Karachi. I remember I used to read his bylines when he was writing for the monthly Newsline. Again, he has the kind of experiences which writers working from within the literary or academic world do not have. Hanif had been a journalist before going abroad. I had spent more than a decade as a police officer. Both Hanif and I started writing after having understood the ground realities of Pakistan. You can say we both had had our skin in the game before we began writing our first novels.

TNS: Can we discuss the process of writing a novel a little bit? Do you think about the plot before you start writing?

OSH: Yes. Usually it is a theme or an idea and I start thinking if it would be good to turn it into a novel. I can give you an example. I have just finished writing a book which I have already sent off to my publisher. The working title is The Fix. It is a novel on match fixing. I started thinking how it would be interesting to explore this grey area. We have a nation that is crazy about cricket. There is a great human cost involved in the whole scandal of match fixing that happened. People have gone to prison. So my forthcoming novel came into existence like this. I also test the worth of an idea by asking myself if it could become a book that I would want to read. If the answer is yes, I go ahead and start fleshing out ideas and try to turn them into a novel.

TNS: Your novels also have a great deal of factual information disguised as fiction. How do you balance the fictional and the real-world elements in your work?

OSH: I do a lot of research if the area is unfamiliar. But when I was writing my first novel I drew upon the people I knew--such as Chaudhry Aslam and other characters. For a first-time novelist, things become easier if the story is based on what he or she is familiar with. Later on, as my work developed, I started creating composite characters. Now it would be difficult for a reader to identify a particular character with a real-world counterpart. If you look at the protagonist of The Spinner’s Tale, you can say it is primarily inspired by the figure of Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh. But Saeed Sheikh is not the sole source of that character. There are bits and pieces of different characters I have met in real life. Some character traits are based on my friends who have no link with any criminal activity. You can say I draw inspiration from real people and create composite and complex fictional characters by mixing their traits.

TNS: You write about crime and you draw on your experiences as a police officer. Do you think you write literary fiction or commercial or genre fiction?

OSH: I really don’t understand the difference between literary or commercial fiction. Maybe it is because of my lack of formal training in literature. But I have come across books that are literary and commercial at the same time. There are some crime writers whose books are also very literary. You know some writers, especially those who have studied creative writing, are very particular about these distinctions and they consciously try to produce literature. Perhaps it is part of their curriculum or training. I am not sure to which category I belong.

TNS: Usually, critics declare a story commercial or literary by looking at how it deals with the moral order. In popular fiction, a crime is a challenge to the existing moral order of a society and the protagonist restores the moral order by the end of the story by solving the crime and making the criminal face the law. You can say, in popular fiction, the plot validates the dominant ideology. Your books are ambivalent towards the social and moral order. Perhaps, that is where the literary value of your work lies.

OSH: Yes. The moral order is restored at the end of my first book but the main character who restores the moral order does not believe in that order. In the first book, I have shown a policeman who finds safety for his family in the house of a courtesan. The other two novels do not restore the moral order at the end. In the second novel, the police are seduced by a terrorist. In the third, a hardened criminal is portrayed in such a way that the reader can empathise with him. I think life is amoral and I try to depict it as such. I also think my books would not have been successful if I had tried to pander to the expectations of those readers whose moral world has a clear division between black and white. I cannot show the police officers as all bad or all good. If there are good and bad police officers in the world, criminals can also occupy an ambivalent position. Life is perhaps somewhere in the grey mix of black and white. I want to explore how criminals can experience moral angst and police officers can be morally ambivalent.

TNS: You must have met such criminals who are going through a moral crisis?

OSH: Yes. Being a police officer helps because I have access to a great deal of extremely interesting content and extremely interesting persons. A lot of criminals and police officers are dealing with their internal struggles and demons.

TNS: How do criminals cross that barrier between the moral side and the criminal side?

OSH: It is linked to the stories they tell themselves. A larger-than-life narrative can help anyone justify a lot of depraved acts. They can justify by saying they were doing it for a great cause--any cause can be aggrandised to that level whether it is political or religious or personal. And when they are caught, they can show remorse and again start thinking like ordinary people.

TNS: How do you reconcile your work as a police officer and your work as a fiction writer?

OSH: I can say one thing for sure. Since I have started writing novels about crime, I have become a better police officer. I am far more observant now. Now when I go somewhere I am also looking at minute details in case I have to describe that situation in a book. So both of my professions are complementing each other. Writing about crime also makes me look at crime more keenly. I pick up a lot of details and observe criminals as potential characters. I am in a unique place as a police officer as well as a writer. I have my fingers on the moral pulse of this society.