Should we relegate these obscure little miseries and ‘negative emotions’ only to the field of psychology and anthropology?

I was still travelling home, between two tube stations, when I was asked to write this piece. I thought about it on the long way home. It seemed to be a dangerous thing to write: I could foresee all the ways in which this could go wrong and eventually would go wrong. I was asked to talk about the positive that comes from negative emotions. I was hesitant. Without having written it, the predictable themes were already unfolding before my eyes. I wondered if there were a right way to talk about it and if, at all, I had access to it.

I approach this piece with the same awkward, anxious slowness with which I stuff my change into my wallet at a till as those queuing behind me wait. I have to start somewhere. I pick an emotion: grief. Words are dangerous. And as it is, they often fall into the wrong hands. I wonder if those hands have ever been mine. I wonder if they still are the ‘wrong hands’ as my fingers stomp across the keyboard with the same manic determination. And as the next question often is, I wonder if I have instead been the wrong person with the right words all along. For I can tell you, the reader, that grief begins with a curly g and ends in a droopy bell-flower f. I can tell you what happens in between is a part of the process.

I look down at my hands. This is a familiar and comfortable sight: My fingers violently pressing the delicate letters of the alphabet spread out on the palate before me. "Be careful, you’ll ruin it with your carelessness," I have been told on many occasions. Maybe these are the wrong hands. Maybe I am the wrong person. And just maybe, I have the wrong words too.

As a woman, the arithmetic of my oppression can be imagined. I can easily use this arithemetic to intellectualise why putting my thoughts out there, using the self as both the subject and part of the vantage point, often feels like a transgression - like I am stirring the pot. Momentarily, I am tempted to check myself. There’s a brief moment of deliberation before you eventually do it.

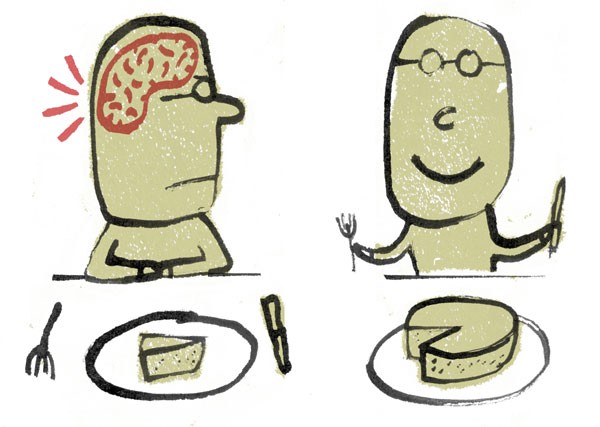

In drawing rooms and at dining tables, as they play the role of ‘the gracious hostess’ at a dinner, I’ve watched women’s eyes glaze over and their thoughts wander to darker places: Maybe I have the wrong words, the wrong thoughts - so many ‘negative’ emotions. God forbid, I feel that I’m onto something, the look says: maybe the kitchen shouldn’t be as clean as it is; maybe I should tear down the wallpaper with tiny red roses on it; maybe the pillows don’t have to be fluffed and the curtains don’t have to be dry cleaned; maybe every individual piece of okra doesn’t need a ghusl before it is tossed around in hot oil. I see how often this train of thought terminates at "garam roti" -- roti (chapati), we know, is best when garam (hot). Garam roti, we also know, leaves very little time for much else.

Should we relegate these obscure little miseries and ‘negative emotions’ only to the field of psychology and anthropology? For social scientists to zoom in on their microscope and pick these issues apart. Someone will pursue this project at the PhD level and find someone already has. Someone will write a book about it. Someone will make a film. They will either get famous doing it or they will fail. Engagement will oscillate from catharsis and theorisation to voyeurism and romanticisation. We will watch, read and talk about the forms at dinner parties until someone says "anyway…"

Without the necessary context, talking about the transformative power of ‘negative’ emotions makes very little sense. Oppression runs across multiple terrains of human existence, and subjectivities. We interact with sociopolitical conditions bigger than ourselves: Sure, even from the ‘depths of despair’ in the Nietzschean sense, we can ‘emerge’; but what about the times when we don’t? Has all of our living gone in vain? What are the dividends here? How does this register in a ‘positive’ or ‘real’ way? For the self, and for the society?

Read also: Editorial

I once sat through a class on Postcolonialism where a student kept asking why postcolonial scholars who were people of colour never wrote in their native languages. "What good does it do for you to keep being angry and resentful about the past? How is that academic theory? Where are your solutions? Look at the bright side and turn that negativity into something positive for yourself and your community," he continued. Bewildered and furious, more so because this was a person of colour, my only response was a filibuster in Urdu -- a language he did not understand.

The question that we fixate on remains unanswered in ways that we would like the answer to arrive: What ‘utility’ can be driven from ‘negative’ emotions? I’m still unsure how exactly to respond to this; except, a few weeks ago, I think I walked past the answer in some graffiti work: "If we spit on them together, they’ll drown".