There is no neat conclusion to be offered on being a mother -- no wise words to resolve a problematic situation. It is what it is…

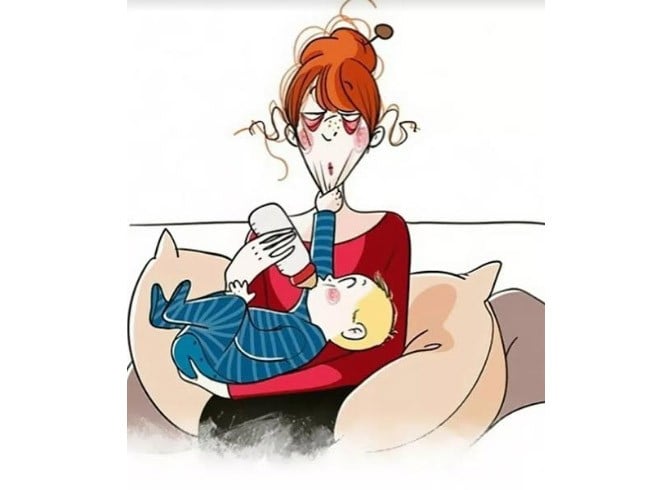

I write this as my sick toddler sleeps an unsettled sleep beside me. I have been kept up all night by her congestion, coughing and fever. I get up quietly and tip toe out of the room to switch off my pinging phone, settle back in front of the laptop, then back again to silence that relentless tyrant, the dish-washer, that has been beeping loudly every five minutes for the past half hour demanding that I attend to it. Now the drier is tooting to be switched off and by this time, I’m exhausted, irritated and have lost my train of thought. Every interruption infuses a little flame of anger that is being fanned into a steady fire that I have lived with ever since I became a mother. It occurs to me that Hell is not fire and brimstone; it is every device you have ever owned ringing loudly at you. All day.

I am supposed to write about motherhood and creativity and what I was going to say, initially, before I was side-tracked, was that motherhood is a combination of loneliness, despair, pain and suffering. Motherhood has subsumed me, but the lethal combination of motherhood and housework is slowly destroying me. Erma Bombeck wrote that ‘Housework, if done right, can kill you’. I wonder now if she was serious. Cleaning is particularly murderous because it gets undone the minute you finish doing it. And tidying up, all day, every day does something strange to your brain.

Let me give you an example -- my husband, b****** that he is, got a Babushka doll for my daughter from Moscow. There are five dolls one inside of each other, each having two pieces and then a last little one that is to nestle at the centre of all the rest. That’s eleven tiny pieces of wood to be thrown under the bed, stepped on, searched for, twisted and scattered about for me to find and reassemble. I hate this toy because the amount of admin required to maintain it is not commensurate to the fun my daughter gets out of it.

I should just leave it alone to get lost or broken, but here’s where the madness comes in -- I can’t function if the Babushka is not complete, smiling benignly at the rest of the apartment from the toy shelf. I feel like a bad mother, a bad homemaker, a bad person if this isn’t so. I have enough awareness to realise that this neurotic perfectionism comes from the feeling that I have given up a vital part of me to stay at home and raise my baby. If everything is not perfect at home, then all that I have sacrificed -- my teaching, my writing, my independence, is for naught. Perfectionism allows me to win at one thing -- housework -- but it means I’m too depleted to do anything else -- like write.

And we all know you never win at housework.

Which is why I am learning to let go of it and with it, the cultural expectations in which I was raised. Expectations that inspected kitchen taps for water stains and tables for dust and floors for dirt because this was a reflection of my womanhood. Expectations that told me to whip up organic vegetable muffins, even if they were ultimately binned because the toddler always prefers flavoured yoghurt. I am realising that a perfectly assembled Babushka doll is immaterial, especially because my daughter is more interested in the telephone and television wires behind the console. Raising a child is draining enough, I have to let other things go.

I have written about the suffering of motherhood but if I take the home-making element out of it, raising your own child is also about intense love, gratitude and contentment. And oddly enough, this combination is a fertile ground for creativity. I feel emotions, usually negative ones, more intently than I had ever done. I observe people more keenly as I feed my child or keep her asleep in my arms, afraid that any movement will wake her up and then my life would belong to her again. And there are times I am happy to give up myself to her -- because unlike any novel I might write, she will love me back.

I have begun to carve out small pockets of time for myself and in these, my inner life reasserts itself with a vengeance. It drove me to rewrite and edit my second novel, and being a mummy with limited time did wonders for my editing skills. I deleted large chunks that weren’t necessary, rewriting them in a style more clipped, more immediate because that was the need of the hour. There was an urgency to my writing that made the manuscript much tighter and more compelling than when I had written it as a single woman with lots of time on her hands.

Now, I have to think of new ways to write a third novel -- I try to write 200 words a day, continuing the story in bits and pieces, not knowing where it will end up. It is an exciting and exasperating process that has yielded me three chapters where the characters tell their own stories because I don’t have the time to faff about, setting up the scene. Motherhood has made me experiment with form to tell a story more directly, to get to the point sooner so we can really start exploring things that matter. It has also slowed me down. When I wrote my first novel, the first three chapters took me four hours. These three chapters, after motherhood, have taken 10 months.

There is no neat conclusion to be offered here -- no wise words to resolve a problematic situation. It is what it is, and one does the best one can. But one thing that motherhood has taught me is that love and suffering are the greatest creative forces in the world and I am grateful for both, in equal measure.