An analysis of the existential challenge Shahmukhi script of Punjabi is facing in Pakistan

In 2016, I reviewed Gurmeet Kaur’s Fascinating Folktales of Punjab for The News on Sunday under the title of ‘Reclaiming Language’. These were children’s Punjabi folktales retold by Gurmeet with beautiful illustrations typeset in Gurmukhi script of Punjabi alongside English translations of the text.

At the end of that review I pleaded to the Pakistani Punjabi publishers and institutions to collaborate with Gurmeet to make these books available for Punjabi kids in Pakistan. She was willing to give rights to print all these books in Shahmukhi keeping the quality of printing intact if someone in Pakistan was interested.

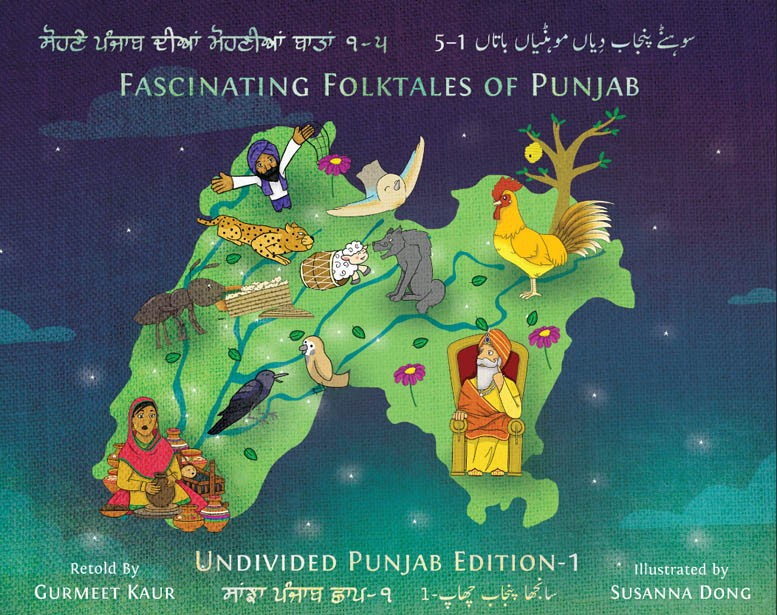

However, as it happens with Punjabi in Pakistan, no one even sent a note of inquiry. In March last year, Gurmeet asked me to join her in editing her first five books ChiDi tay Pippal (The Sparrow and the Pippal tree), ChiDi tay Kaa(n) (The Sparrow and the Crow), Lailaa tay Dhol (The Lamb and the Dhol), Jatt tay Ghuggee (The Farmer and the Dove) and BhukhhaD KeeDee (The Very Hungry Ant) into a single large sized art paper book (11 x 8.5) with text both in Shahmukhi and Gurmukhi scripts of Punjabi alongside English translations and Graphics. We decided to name it Sanjha Punjab Chhaap (Undivided Punjab Edition). This book was finally launched in Lahore by LUMS, LGS (Lahore Grammar School), PILAC (Punjab Institute of Language, Art and Culture) and Lyallpur Literature Festival in February of this year.

During the entire process of composing, printing and designing of UPE (Undivided Punjab Edition), a few important revelations and roadblocks related to Shahmukhi script of Punjabi jolted me to write this piece so that I could bring to fore what kind of an existential challenge our script is facing. The script of Punjabi that was used by Baba Farid, Waris Shah, Shah Hussain, Bulleh Shah, Hafiz Barkhurdar, Peelo, Nijabat, Qadir Yar, Hashim Shah, Shah Muhammad, Mian Muhammad Baksh, Khawaja Farid and well read by Baba Nanak and other Gurus.

First challenge while transliterating from Gurmukhi to Shahmukhi was to incorporate ‘ARnoon’ (also known as Aroonڻ). ARoon is the sound used in the word ‘PaaNi’ (water) by Punjabis as it is PaaNi in Punjabi and not Paani. Gurmukhi has a dedicated alphabet for this sound called ‘NaaNa’ (ਣ) while in Shahmukhi we haven’t yet agreed to a standard alphabet/character. When Punjabi Adabi Board used to publish from hand-written manuscripts, an extra dot was manually placed on top of ‘noon’ (ن) to announce the difference. However, with arrival of digital printing and Inpage typing software, even Adabi Board abandoned these efforts and started using ‘noon’ both for the ‘noon’ sound as well as for ARnoon apart from one book where (ڻ) was used by board.

Then as far as Inpage is concerned it was developed specifically for Urdu language and as Urdu has no ARnoon sound; many Punjabi publishers using Inpage religiously, quickly dropped an entire Punjabi alphabet from their prints leaving the difference between noon and ARnoon to readers to figure out for themselves. Some of the Punjabi publishers notably Suchet and Punjabi Markaz kept using some other special symbols on top of noon for differentiation but Punjabis across board didn’t agree on a single unified character for ARnoon.

Therefore, me and Gurmeet decided to follow our Seraiki friends and started using (ڻ) to write ARnoon. As Inpage doesn’t have this character available and as our initial transliteration was in Inpage, we decided to move the entire text into Unicode in Microsoft Word. After installing all available Urdu fonts in Windows for Word, we found out that apart from Alvi Nastaleeq and Roz, none of other Urdu fonts have (ڻ) available to use in Unicode. Whereas even in these two fonts ARnoon was only available as a symbol that needs to be inserted as a special character every time through the insert tab and cannot be typed with a key stroke.

After handling ARnoon, we moved to another missing alphabet not used by Punjabi publishers and printers in Pakistan ie ‘ARlaam’. ARlaam refers to the sound used in Punjabi areas while pronouncing words like ‘rola’, ‘kaala’, ‘pippal’, ‘naal’ etc. as this sound is not a ‘laam’ sound but an ARlaam sound. In Gurmukhi for ARlaam there is a separate alphabet called ‘Lallay Pairee Bindi’ (ਲ਼) ie a dot under laam. While here in Shahmukhi we don’t even incorporate it and none of the above Urdu scripted fonts have this character even as a symbol. Therefore, we decided to follow the Gurmukhi rule and put a dot under laam manually and included it just in one of the stories ‘ChiRi tay PippaL’.

However, our scripting pain didn’t end there. When our Hong Kong based graphic designer Chaaya Parbhat tried to import Shahmukhi Unicode text into Adobe’s ‘In Design’ for graphics, a new hell broke loose. At some places the hook of Heh ( ) was lost, somewhere ‘zairs’ and ‘zabbars’ were missing, dots of many alphabets disappeared and

( ) became unrecognisable, closing and opening quotes got mixed up and so on. We found out that all this mess happened due to non-standardisation of our fonts and incompatibility issues with Adobe and Microsoft for these characters. We had no such issue as far as the Gurmukhi script was concerned. As Chaaya can’t read or write Urdu or Punjabi (Shahmukhi or Gurmukhi), and all three of us were sitting across the seas; to point out each faulty line number, to the point of each alphabet to be corrected manually in ‘In Design’, was a painfully long process.

There were many other such issues but I will stop here to point out and focus on the main reason for detailing this ordeal. It is related to the existential threat being faced by Shahmukhi script and Punjabi Shahmukhi printing due to a lack of standardisation and an incomplete script inclusion by global software companies like Microsoft, Adobe, Apple et al. Most importantly our lack of coordination with the Unicode consortium to get Shahmukhi accepted and released as a standard Punjabi script. This can only happen with the help of IT professionals, for example of PITB, ITU or UET language and computing centres. Otherwise, a day will come when we may still be speaking Punjabi in Pakistan, but we will have no standard tools to type or print Punjabi books professionally and with authenticity. We have already deprived Punjabi readers from ARnoon and ARlaam sounds since long and we need to claim those back as well as urgently connecting with global Tech companies so that all graphics, imaging, printing and post production softwares can incorporate complete Punjabi alphabets, sounds, styles and fonts of Shahmukhi.

There is no quick fix and we need passionate Punjabi IT professionals to lead us because approval of any new character or script by Unicode Consortium (UC) before its included by global companies in their releases, takes years and even to qualify for a submission of any new character proposal, UC asks for the name and contact information for a company or individual who would agree to provide a computerised font (True Type or PostScript) for publication of the standard; references to dictionaries and descriptive texts establishing authoritative information; names and addresses of appropriate contacts within national body or user organisations; and the context within which the proposed characters are used (for example, current, historical, and so on).

Therefore, we need to start this process before it’s too late and we are left with just Urdu fonts and sounds. I hope that organisations like PILAC and Punjabi Adabi Board can take it seriously.

Coming back to Folktales of Punjab: Undivided Punjab Edition, let me share another interesting ‘situation’. When the book was finally published and launched in Lahore, major distributors declined to distribute it saying that it carries an ‘Undivided Punjab’ name and map on the book cover. The map we used is that of Partition Plan of 3rd June 1947 which is part of every Punjab Partition history book across libraries. Exactly the same map was used on the book cover of Rajmohan Gandhi’s Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten which was proudly distributed by same distributors across Pakistan but somehow, a Punjabi language book for children wasn’t worth their shelves!

Fascinating Folktales of Punjab: Undivided Punjab Edition

Author: Gurmeet Kaur

Price: USD20

Pages: 94