The rise of the far right, as at the time of Joseph Roth, poses an ever present threat to the European values of tolerance, diversity and cosmopolitanism

In 1936, in the seas town of Ostend, in Belgium, a group of Austrian writers on the run from Nazism gathered for the last time before scattering abroad in exile to meet early and, untimely, deaths. The get-together is aptly called the summer before darkness of full blown fascism fell upon Europe.

Among those gathered were two German writers: Joseph Roth and Stephan Zweig. Both were fervent priests of the lost world of high European civilization they helped nourish before the First World War. Joseph Roth was the first to go to grave when he died in 1938. His early exit to grave was triggered by his excessive drinking. Four years later, Stefan Zweig also committed suicide.

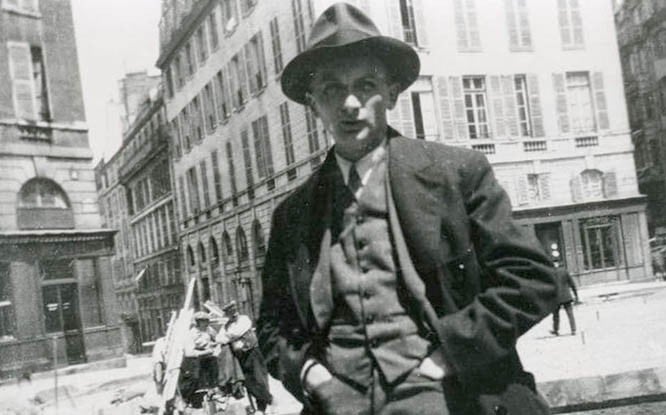

Of all writers, Joseph Roth was an eminent journalist and one of the great novelists of German language classed with Kafka and Musil.

Roth was born in Brody, in what was then Poland, and now Ukraine. His father was committed to mental asylum when he was four. A brilliant student, Roth excelled at German literature at the university. Although he held pacifist inclinations, he enrolled in the military service as a media man in the first war. The war reduced the fabled city of Vienna to its physical size previously magnified by the vastness, grandeur and diversity of the Habsburg Empire. The decline in the artistic and cultural diversity of the city deeply affected Roth.

Soon after the war, he began his career as a journalist with a new left wing weekly which folded within months of Roth’s entry. In 1923, the Frankfurter Zeitung, a liberal paper, employed him in its Berlin office as its one of the best paid journalists of the time. There he excelled at mastering feuilleton -- a short political commentary on happenings of the day or a particular event experienced by the writer. Roth took immense pride in refining and promoting this genre in journalism (In Pakistan, the weekly Viewpoint carried regular column under the same title feuilleton contributed by Khwaja Masud, I guess).

During his employment with the newspaper, Roth travelled to various European countries such as Albania which widened his view of the diverse European civilization. His travel pieces were later collected into The Hotel Years: Wanderings in Europe Between the Wars. In some sense, this summed up Roth’s peripatetic and provisional existence.

In 1925 he was transferred to Paris by the newspaper. He loved Paris and strove to make his mark there by interesting himself in French literary circles by writing The Hundred Days, an account of Napoleon’s return after his flight from Elba.

Like Stephan Zweig, he was much affected by the first world which he saw as the destroyer of theEuropean civilization as he knew it before the war. However, unlike Zweig, he was more politically committed to the cause of antifascism. His novel, The Spider’s Web, had predicted the rise of Hitler and fascism in Germany.

The troubles began to pile up when he lost job with the German newspaper. From this point onward, all his days and nights were consumed in hard labour to feed his mouth. He lived in hotels in Paris for all the days of his life in exile. There he spent, routinely, his whole day in writing in a nearby café while chasing his publishers for advances in Amsterdam and Europe.

Joseph Roth has been called the emperor of nostalgia. His preoccupation was with the Habsburg Empire which, for him, represented cosmopolitanism, diversity and tolerance at its height -- high European values. Jews under the Habsburg were left alone to pursue their intellectual and financial pursuits without being molested by the state. The fall of the Habsburg Empire, in the wake of the First World War, shattered the cozy comfortable existence for Jews. The rise of fascism was the exact opposite of what the Habsburg Empire represented. Nazism was a race-based exclusive creed which excluded and targeted the Jews.

Joseph Roth’s masterpiece, Radetzky March, published in 1932, established his lasting reputation as one of the best German writers. The novel showcases Roth’s long-held fascination with the Habsburg Empire. The decline and fall of the Empire is shown in the rise and fall of the newly ennobled family of Trotta.

The title of nobility is conferred upon the family’s patriarch Captain Joseph Trotta for saving life of the emperor Franz Joseph at the battle of Solferino in 1859. Yet the Trottaline sees progressive decay with each generation in the line. The heroic act of the founder of the dynasty binds all generations of the Trottas to the glory of the Empire and the founder of the dynasty. The younger Franz Trotta joins civil service of the empire. yet feels himself inadequate to the heroics of the Trotta senior. In turn, his son, Carl Trotta joins the military service but feels, equally, quite empty of the larger purpose which embodied his illustrious grandfather and the once mighty Hapsburg Empire.

Carl dies in action in the first world war. Carl’s fate mirrors that of the empire. Carl is passive and lacks the will to move beyond the shadow of the legend of his grandfather. He lives off his grandfather’s reputation as the Empire fed off its past glory.

Biblically speaking, by the slothfulness of the Trottas the edifice of the empire decayed; and through idleness of the hands of new generations and the eruption of nationalistic insurrections the house of the Habsburg dropped through history into oblivion.

The themes of Radestsky March again recur in The Emperor’s Tomb where the great nephew of the Captain Trotta is resurrected. The story of Roth, as described in his fiction and nonfiction, is the story of our age of displacement, conflict and exile and the decline of European values. This explains the enduring relevance of Roth’s work and bleak vision at a time when Europe is heading in the populist and xenophobic direction.

The rise of the far right, as at the time of Roth, poses an ever present threat to the lasting European values of tolerance, diversity and cosmopolitanism.