Machiavellian counsel should compel us to imagine the wonderful things that may happen in Pakistan if we go forward by going back to Jinnah’s principles of good governance

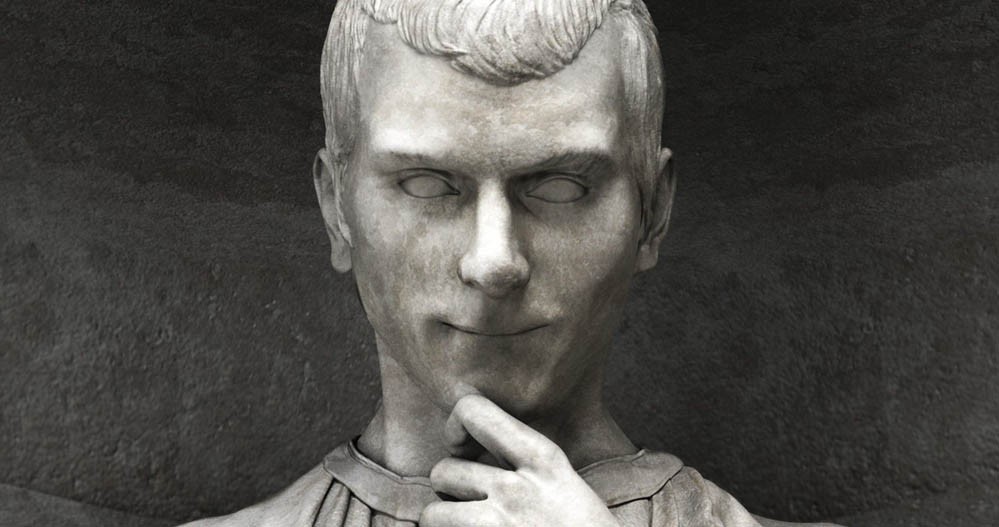

Nicolo Machiavelli (1469-1527), the Renaissance Florentine political thinker, is globally renowned as the author of the political tract The Prince that is generally considered to be the classic book for conducting no-holds-barred power politics. However, it is in his lesser-known work The Discourses, composed as a commentary on Livy’s (59 BC - AD 17) history of ancient Rome, that Machiavelli sets himself the remarkable task of laying down conditions and caveats for founding and running republics of free people.

This work is a brilliant, if at times unconventional, defense of democracy long before democracy became the cornerstone of the global political order. One of its striking features is Machiavelli’s claim that "… in it I have set down all that I know and have learnt from a long experience of, and constantly reading about, political affairs."

Right in the beginning, Machiavelli states his unequivocal belief in stable inclusive government. However, his vision of inclusiveness appears counterintuitive. To him, inclusive government is one that combines three types of what he calls good government, i.e., "Principality, Aristocracy and Democracy". He believes such a mixed government would prevent the emergence of tyranny, oligarchy, and anarchy in a republic.

If executive and central decision-making, inherited or acquired social status and privilege, and popular choice are the key organising principles of monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic forms respectively, then it is amazing to notice how regimes of various stripes today seek legitimacy, and become functional through institutionalising acceptable and viable combinations of these key principles.

The work proclaims that "… government by the populace is better than government by princes." This pro-people preference is founded on the claim "that the populace is more prudent, more stable, and of sounder judgment than the prince." For Machiavelli, this "sounder judgment" arises out of the natural collective propensity of the people to choose the better alternative, whether it is a question of choosing public officials or choosing viewpoints.

To Machiavelli, it is not just the innate ability to make the right decision that people possess that makes popular government desirable. To him, popular government founded on the rule of law is a practical way of checking the proclivity of humans for intra-group and inter-group disorder, conflict, and animosity. Machiavelli is one of the earliest modern thinkers to stress the link between justice, democracy, and peace.

Machiavelli further stresses the connection between accountability, transparency, and democratic governance by maintaining that corruption of the political order undermines democratic and republican values and paves the way for non-democratic governance. Since a corrupt political order, he argues, will rarely consent to its own reform by democratic means, other measures have to be sought to remedy its ills. This caveat enjoins the political class as a whole to prize and cultivate probity as the strongest bastion of democracy.

Machiavelli cautions that the tendency of people to lionize charismatic individuals and hastily put power in their hands proves detrimental to democracy. Equally dangerous in his estimation is the popular urge to seek sudden removal of such individuals from power. Rather, Machiavelli prescribes patient evaluation of the situation and advocates decisive corrective action only if it can succeed. Maintenance of social stability and public order are the two standards of successful corrective action for him.

His advice to tackle the systemic malaise that confronts a state in crisis is equally profound. In much the same manner in which computers or smartphones are formatted to their factory settings to get rid of viruses and ensure speedy and smooth working, Machiavelli advised almost five centuries ago that a state that wishes to overcome its intractable challenges and wants to exist for a long time should reinvigorate itself by occasionally reverting to the first principles on which it was founded in the beginning.

It needs to be mentioned that this reversion happens to be the most challenging aspect of reforms and seldom have states succeeded in undertaking it comprehensively. What is badly needed usually turns out to be terribly difficult.

This uncanny correspondence between computing and Machiavelli’s observations on statecraft points to the abiding historical connections between political, scientific, and technological domains of human endeavour. Societies that have built popular meritocratic flexible institutions and dynamic mechanisms to develop and sustain these connections have forged ahead of the rest.

In our own Pakistani context, this Machiavellian counsel should compel us to imagine the wonderful things that may happen in Pakistan and, by extension, in South Asia if we go forward by going back to Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s principles of good governance based on fairness, integrity, pragmatism, institutional stability, and a horses-for-courses approach for getting things done.