While both maps and flags represent the concept of a country, it can be a matter of confusion for a creative person

With flags fluttering around and national anthems being played on radio and television, a sense of jubilation and patriotism captures the air around August 14 each year. Patriotism means ‘vigorous support for one’s country’. It also entails defending national boundaries against an invading enemy, often considered a sublime mission.

Territory of a country is defined and determined through its map. In the case of Pakistan, the map has constantly changed in the different phases of our existence. For instance, the status of Khairpur, the whole of Balochistan, Swat and more recently Gilgit Baltistan have altered in the last 70 years. The biggest change in the map occurred when the bigger half of the country separated and called itself Bangladesh. Jammu and Kashmir is another grey area on the map of subcontinent.

So whatever happens in the future will not change history; it will only change cartography and the subsequent sentiments of nationhood. This is not something peculiar to our part of the land. In the twentieth century, many countries including Palestine, Germany, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sudan, Puerto Rico, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, USSR and the Gulf states went through transformation of borders.

Thus, a map of a country is both sacred and superficial at the same time because no one is sure how long the borders and sovereignty of a state may stay intact. Some countries, like the United States (US), have a single map in circulation for a century. Artists like Jasper Johns, American painter and sculptor, have therefore treated the country’s map as a common image. Johns has also painted a number of US flags because, like map, a flag is another sign of a country’s identity.

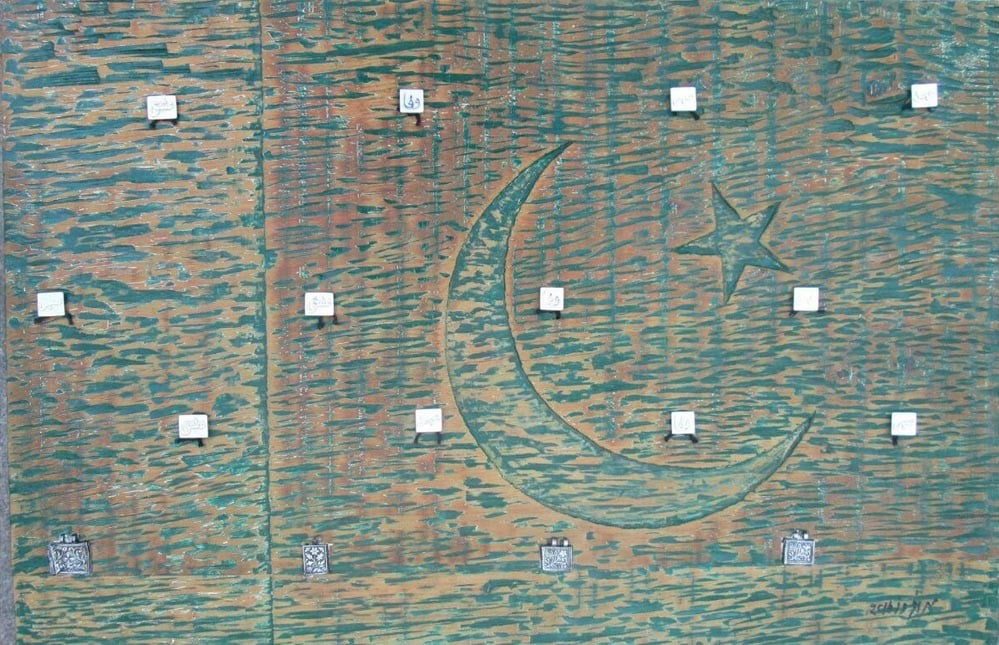

Sara Rahbar on the other hand has used the American flag as a substitute to the idea of Imperialism. Muhammad Zeeshan has explored possibilities in flags of different countries. Artists like Mehr Afroze, Ali Azmat, Sajid Khan and several others have created national flags in their works (from the exhibition I Live Pakistan, 2016, a project of Studio R. M.). Recently, Sania Samad is reinterpreting the same visual in different ways.

While both maps and flags represent the concept of a country and a sense of belonging, it can be a matter of confusion for a creative person. Agha Shahid Ali, the poet from Kashmir, describes his homeland as ‘The Country without a Post Office’ (also the name of his collection of poems), but many authors and artistes live in a ‘post office’ without a country. This post office is not their email account but their art.

When we read something by Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Derek Walcott, V. S. Naipaul, Peter Carey, Paul Beatty, Arundhati Roy or Julian Barnes, we know of their place of origin but it is their language -- English -- that makes them citizens of a Commonwealth.

A similar scenario can be surmised with writers of other widely used tongues, for instance, Portuguese used in Portugal, Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and East Timor; Spanish along with motherland in Columbia, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Paraguay, Panama, Ecuador, Chile, Cuba, Nicaragua, Honduras and Mexico; or Arabic used by authors of Middle Eastern countries.

In the realm of pictorial arts, the question of nationality is even more complex because an image is not landlocked. A visual artist can communicate without revealing his origin; mainly because a painting, print, sculpture or installation does not depend on being translated. It can be accessed, enjoyed and understood by people across a geographical spectrum.

Garcia Marquez claims that the best reader of his novel One Hundred Years of Solitude is a cab driver from Colombia. Yet people from all continents appreciate the book; each through his own experience. Similarly, a work of art is open to multiple interpretations across the globe, something that makes the life of an artist both easy and difficult. In a world of political divides, an artiste may belong to more than one region. But when dealing with his work, those links become essential. One cannot deny or remain detached from one’s immediate surroundings. References from geography, culture and tradition do enter the work of a creative person. But the crux of the matter demands certain decisions. Starting from allegiance to a particular location, religion, race, sex and ideology, many artists opt for these positions (pegs), because they feel that art is (about) the personal history of the maker.

The other crucial question is of choice. Does being born into a nation, faith, family, profession, caste, class, gender, ethnicity and language oblige a creative person to represent what was given to him/her as birth present? Or can they negate all these connections and produce something unrelated to these initial identities?

It is perhaps more possible in the world of today because even though we physically live in a country, we are residents of many places. A painter from Nigeria may decide to make canvases on Tantric art, or a Mexican artist would be interested in exploring Indian miniature painting, a novelist from Syria can base his fiction on the suburbs of Sao Paulo, or a singer from Peshawar may like to incorporate Jewish songs in her music.

It is possible but remains problematic, only because we are so accustomed to framing an individual within his national identity that any deviation causes confusion. Kazuo Ishiguro points out this general expectation from a writer with a name like him (and oriental features) to write on Japanese subjects whereas he is an ‘English author’.

Perhaps national borders exist in our minds more than on maps or on physical terrains. We tend to confine ourselves in these seclusions without knowing that an artist can belong to anywhere as long as he resides in his art. Postal address is not as important as what is contained in the post.